|

|

Public Domain text

transcribed

and prepared "as is" for HTML and PDF

by Richenda Fairhurst, historyfish.net. July 2007. No commercial permissions granted. Text may contain errors. (Report errors to  ) ) |

CHAPTER IX EXTERNAL

RELATIONS OF

THE MONASTIC ORDERS Normally, the bishop of the

diocese in which a religious house was situated, was its Visitor and

ultimate authority, except in

so far as an appeal lay from him to the pope. In process of time

exemptions from the regular jurisdiction of the

diocesan tended to multiply ; whole Orders, like the Cistercian and the

Cluniacs among the

Benedictines, and the Premonstratensians among the Canons Regular, and

even

individual houses, like St. Alban’s and Bury St. Edmunds, on one ground

or

another obtained their freedom from the jurisdiction of the Ordinary.

In the case of great bodies, like those of

Citeaux, Cluny, Prémontré, and later the Gilbertines, the

privilege of exemption was in the first

instance obtained from the pope, on the ground that the individual

houses were parts of

a great corporation with its center at the mother-house. Such

monasteries were all subject to the

authority of a central government, and regular Visitors were appointed

by

it. In the thirteenth century, on the same principle, the mendicant

Orders, whose members were attached to the

general body and not to the locality in which they might happen to be,

were freed from

the immediate control of the bishops

--180-- In the case of

individual houses, the exemption was granted by the Holy See as a

favour and a privilege. It

is hard to understand in what the privilege really consisted, except

that it was certainly considered an honourable thing to be immediately

subject only to the head of the Christian Church. Such privileges were,

on the whole, few ; only five

Benedictine houses in England possessed them, and even such great and

important abbeys as Glastonbury,

in the South of England, and St. Mary’s, York, in the north, were

subject to the regular jurisdiction of the diocesan. In the case of the

few Benedictine houses

which, by the intercession of the king or other powerful friends, had

obtained

exemption in this matter, regular fees had to be paid to the Roman

chancery for

the privilege. St. Alban’s, for example, at the beginning of the

sixteenth century, made an annual

payment of £14 to the papal collector in lieu of the large fees

previously paid

on the election of every new abbot, and as an acknowledgement of the

various privileges

granted to him, such as, for example, the right to rank first in

dignity among

the abbots, and for the abbot to be able “even outside his own churches

to use pontificalia

and solemnly bless the people.” Edmondsbury, in the same way, paid an

annual sum for its

exemption and privileges, as also did Westminster, St. Augustine’s

(Canterbury), Waltham Holy Cross, and a few others. By this time, too,

some of the Cluniac houses, such as Lewes Priory and

Lenton, had obtained their exemption and right of election. In regard to the non-exempt monasteries and convents—that is ordinarily—the relation between the bishops and --181-- the religious

houses was constant ; and, apparently, with exceptions of course,

cordial. The

episcopal registers show that the bishops did not shirk the duty of

visiting,

and correcting what they found miss in the houses under their control ;

and

whilst there is evidence of a natural desire on their part to bring the

regular

life up to a high standard, there is little or none of any narrow

spirit in the

exercise of their part of the episcopal office, or of any determination

to

worry the religious, to misunderstand the purpose of their high

vocation, or to

make regular life unworkable in practice by any over-strict

interpretation of

the letter of the law. It is, of course after all, only natural that

these good relations should exist between

the bishop and the regulars of his dioceses. The unexempt houses were

not extra – diocesan so far as

episcopal authority went, like those of the exempt Orders ; but they

were for the

most part the most important and the most useful centres of spiritual

life

in each diocese. It was therefore to the

bishop’s interest as head of the diocese to see that in theses

establishments the lamp of fervour would not be allowed to grow dim,

and that the good

work should not be permitted to suffer through any lessening on the

cordial

relations which had traditionally existed between the bishops and the

religious houses within the pale of his jurisdiction. The bishop’s duties to the religious houses in his diocese were various. In the fist place, in regard to the election of the superior : here much depended upon the actual position of the monastery in regard to the king, to the patron, or even to the Order. If the king was the founder of the house or had come to be regarded as such, which may roughly be said to have been the case in most --182-- of the greater

monastic establishments, and especially in

those which held lands immediately from the Crown, then the bishop had

nothing to say to the matter till the royal assent had been given. The

process has been already briefly

explained ; but the main features may again be set out. On the death of

the superior, the religious

would have to make choice of some of their number to proceed to the

court to inform the king of the demise and to obtain the congé

d’ élire, or permission to elect. The first action of the

king would be the

appointment of officials to administer the property in his name during

the

vacancy, having due regard to the needs of the community. He would then

issue his license for the

religious to choose a new superior. All this, especially if the king

were abroad or in some far-off part of the

country, would take time, sometimes measured by weeks. On the reception

of the congé d’

élire, the convent proceeded to the formal election, the

result of which had to be reported to the king ; and if he assented to

the choice made, this was signified to the bishop, whose office it was

to inquire

concerning the validity of the election and the fitness of the person

chosen—that is, he was bound to see whether the canonical forms had all

been

adhered to in the process and the election legal, and whether the elect

had the

qualities necessary to make a fitting superior and a ruler in temporals

and in

spirituals. If after inquiry all proved to be satisfactory, the bishop

formally confirmed the choice of the

monks and signified the confirmation to the king, asking for the

restitution of temporalities to the new superior. If the election was

that of an abbot, the bishop then bestowed the solemn blessing up on

the elect thus confirmed, generally in some place other than --183-- his own

monastic church, and wrote a formal letter to the

community, charging them to receive their new superior and show him all

obedience. Finally, the bishop appointed a commission to proceed to the

house and install the abbot or prior in

his office. In the case of houses which

acknowledged founders or patrons

other than the king, the death of superiors were communicated to them

and

permission to proceed to the choice of successors was asked for more as

a form than as a reality. The rest was in the hands of the bishops. In

ordinary

circumstances where there was no such lay patron, a community, on the

death of

a superior, merely assembled and at once made choice of a successor.

This election had then to be communicated at once to the bishop, whose

duty it was to inquire into the circumstances

of the election and to determine whether the canonical formalities had

been complied

with. If this inquiry proved satisfactory, the bishop proceeded to the

canonical examination of the

elect before confirming the choice. This kind of election was completed

by the issue of the episcopal letters

claiming the obedience of the monks for their new superior. It was

frequently the custom for the bishop to appoint

custodians of the temporalities, during the vacancy at such of those

religious houses as

were immediately subject to him. The frequency of the

adoption by religious of the form of election by which they requested

the bishop to make chose of their superior is at least evidence of the

more than

cordial relations which existed between the diocesan and the regulars,

and of

their confidence in his desire to serve their house to the best of his

power in

the choice of the most fitting superior.

--184-- Sometimes, of course, the

Episcopal examination of the

process, or of the elect, would lead to the quashing of the election.

This took place generally when some canonical

form had not been adhered to, as on this matter the law was rightly

most strict. Less frequently, the elect on inquiry was

found to lack some quality essential in a good ruler, and it then

became the duty of the bishop to declare the choice void. Sometimes

this led to the convent being deprived of its voice in the

election, and in such a case the choice devolved upon the bishop.

Numerous instances, however, make it clear

that although legally the bishop was bound to declare such an election

void, he would always, if possible, himself appoint the religious who

had been

the choice of the community.

In other instances again, the bishop’s part in the appointment of a new superior was confined to the blessing of the abbot after the confirmation of the election by the pope, or by the superior of the religious body. This was the case in the Cistercian and Cluniac bodies, and in such of the great abbeys as were exempt from episcopal jurisdiction. Sometimes, as in the case of St. Alban’s, even the solemn blessing of the new abbot could by special privilege be given by any bishop the elect might choose for the purpose. Outside the time of the elections and visitations, the bishops exercised generally a paternal and watchful care over the religious houses of their diocese. Before the suppression of the alien priories, for example, those foreign settlements were supervised by the Ordinary quite as strictly as were the English religious houses under his jurisdiction. These priories were mostly established in the first instance to look after estates which had been --185-- bestowed upon foreign abbeys,

and the number in each house

was supposed to be strictly limited, and was, in fact, small. It was

not uncommon, however, to find that

more than the stipulated number of religious were quartered upon the

small

community by the foreign superior, or that an annual payment greater

than the

revenue of the English estate would allow was demanded by the

authorities of

the foreign mother-house. Against both of there abuses the bishop of

the dioceses had officially to guard. We find, for instance, Bishop

Grandisson of Exeter

giving his licence for a monk of Bec to live for some months only at

Cowick

Priory, and for another to leave Cowick on a visit to Bec. Also in

regard to

Tywardreath, a cell of the Abbey of St. Sergius, near Ghent,

the same bishop on examination found that the revenue was so diminished

that it

could not support the six monks it was supposed to maintain, and he

therefore

sent back three of their number to the mother-house on the continent.

This conclusion, be it remarked, as arrived at only after careful

inquiry, and after the bishop had for a time appointed a

monk from another religious house to assist the foreign superior in the

administration of the temporals of his priory. Upon the report of this

assistant he deprived the superior for

negligence, and appointed custodians of the temporalities of the house.

From the episcopal registers generally

it appears, too, that once the foreign religious were settled in any

alien

priory, they came under the jurisdiction of the bishop of the locality,

in the

same way as the English religious. The alien prior’s appointment had to

be confirmed by him, and no religious could come to the house or go

from it, even to return to the foreign mother-house,

without his permission.

--186-- In regard to

all non-exempt monastic establishments of men and convents of women,

the episcopal powers were very great and were freely exercised. This to

take some examples :

the Benedictine abbey of Tavistock in the fourteenth century was

seriously

troubled by debt, partly, at least, caused by an incapable and unworthy

superior. This abbot, by the way, had been provided by the pope; and

apparently the bishop did not consider

that his functions extended beyond issuing a commission to induct him

into his

office. In a short time matters came to a crisis, and

reports as to the bad state of the house came to the ears of Bishop

Grandisson. He forthwith prohibited the

house from admitting more members into the habit until he had had time

to examine into matters. The abbot replied

by claiming exemption from episcopal jurisdiction, apparently on the

ground that he had been appointed by the Holy See. The

bishop, as he said, “out of reverence for the lord Pope who had

created the both of us,” waived this as a right and came to the house

as a

friend, to see what remedy would be found to allay the rumours that

were rife

in the country as to gross mismanagement at the abbey. How far the

bishop succeeded does not

transpire ; but a couple of years later the abbot was suspended and

deposed,

and the bishop appointed the Cistercian abbot of Buckland and a monk of

Tavistock to administer the goods of the abbey pending another

election. How thoroughly the religious approved of the

action of the bishop may be gauged b the fact that they asked him to

appoint

their abbot for them. In the ordinary and

extraordinary visitations made by the bishop, the interests of the

religious houses were apparently the only

considerations which weighed with

--187-- him. Sometimes

the injunctions and monitions given at a visitation appertained to the

most

minute points of regular life, and sometimes the visitatorial powers

were

continued in force for considerable periods in order to secure that

certain point

that needed correction might be seen to. One curious right possessed

and exercised by the bishop of any diocese on first coming to his see,

was that of appointing one person in each monastery

and convent to be received as a religious without payment or pension.

It is proper, however, to say that this right

was always exercised with fatherly discretion. Again and again, the

records of visitations in the

episocpal register show that the bishop did not hesitate to appoint a

coadjutor to any superior

whom he might find deficient in the power of governing, either in

spirituals or

temporals. Officials who were shown to be incapable in the course of

such inquires were removed, and others were

either appointed by the bishop, or their appointment sanctioned by him.

Religious who had proved themselves

undesirable or impossible in one house were not unfrequently translated

by the

bishop to another. This is A.D. 1338-9

great storms had wrought destruction at Bodmin. The priory buildings

were in

ruins, and a sum of money had to be raises for the necessary repairs

which were

urgently required. Bishop Grandisson gave his permission for the monks

to sell a corrody—or undertaking to

give board and lodging for life at the priory—for a payment of ready

money. A few years later, in 1347, on his visitation the bishop found

things financially in a bad way. He removed the almoner from his

office,

regulated the number of servants and the amount of food ; and having

appointed

an administrator --188-- sent the prior

to live for a time in one of the priory

granges, in order to see whether the house could be recovered from its

state of bankruptcy by careful administration. One proof of the friendly

relations which as a rule existed between

the bishop and the regular clergy of his diocese may be seen in the

fact thatthe abbots and superiors were frequently, if not generally,

found in the lists

of those appointed as diocesan collectors on any given occasion. The

superiors of religious houses contributed

to the loans and grants raised in common with the rest of the diocesan

clergy,

either for the needs of the sovereign, the Holy See, or the bishop.

That there were at times difficulty and

friction in the working out of these well-understood principles of

subordination

can not be denied ; but that as a whole the system, which may be

described as

normal, brought about harmonious relations between the bishop and the

regulars

must be conceded by all who will study its workings in the records of

pre-Reformation episcopal

government.

2. The Church In England Generally The monastic Orders were called

upon to take their share in

common burdens imposed upon the Church in England. These included

contributions to the sums

levied upon ecclesiastics by Convocation for the pope and for the king

in times of need ; and they contributed, albeit, perhaps, like the rest

of the English Church, unwillingly, their share to the “procurations”

of papal legates and questors. Sometimes

the call thus made upon their revenues was very considerable,

especially

--189-- as the king did not hesitate on

occasions to make particular

demands upon the wealthier religious houses. At Convocation, and in the

Provincial Synods the regular

clergy were well represented. Thus, from the diocese of Exeter in the

year

1328-9 there were summoned to the Synod of London seven abbots to be

present personaliter, whilst five Augustinian and

seven Benedictine priories also chose and sent proctors to the

meeting. As a rule, apparently, at all such meetings the abbots, and

priors who were canonically elected to

rule their houses with full jurisdiction, had the right, and were

indeed bound to

be present, unless prevented by a canonical reason. The

archbishop, as such, had no more to say to the regulars than to any

other ecclesiastic of his province, except

that during a vacancy in any diocese he might, and indeed frequently

did, visit the

religious houses in that diocese personally or by commission.

Besides supervision and help of

the bishop, almost every

religious house had some connection with and assistance from the order

to which it belonged. In the case of the great united corporations like

the Cluniacs, the Cistercians, the

Premonstratensians, and later the Carthusians, the dependence of the

individual monastery

upon the centre of government was very real both in theory and in

practice. The abbots or superiors had to attend at General Chapters,

held, for instance, at Cluny,Citeaux, or Prémontré, and

were subject to regular visitation made by or in behalf of the general

superior. In the

case of a vacancy the election was

--190-- supervised and the elect

examined and confirmed either by,

or by order of, the chief authority, or, in the case of

daughter-houses, by the

superior of the parent abbey. Even in the case of the Benedictines, who

did not form an Order in the modern

sense of the word, after the Council of Lateran in 1215, the

monasteries were

united into Congregations, for common purposes and mutual help and

encouragement. In England there were two such unions, corresponding to

the provinces of Canterbury

and York, and the superiors met at regular intervals in General

Chapters. Little

is known of the meetings of the Northern Province

; but in the South the records show that they were regularly held to

the last. The first and ordinary business of thee General Chapters was

to secure a proper standard of regular

observance ; and whatever, after discussion, was agreed upon, provided

that it met

with the approval of the president of the meeting, was to be observed

without any appeal. Moreover, at each of these Chapters two or more

prudent and religious men were chosen to visit every Benedictine

house of the province in the pope’s name, with full power to correct

where any

correction might be considered necessary. In case these papal Visitors

found abuses existing in any

monastery which might render the deposition of the abbot necessary or

desirable, they

had to denounce him to the bishop of the dioceses, who has to take the

necessary steps for his canonical removal. If the bishop

did not, or would not act, the Visitors were bound to refer the case to

the Holy See. By the provisions of the Lateran Council in A.D. 1215,

the bishops were warned to see that the religious houses in their

dioceses were in

good order,

--191-- “so that when the aforesaid

Visitors come there, they may find them worthy of commendation rather

than of correction.” They were, however, warned to be careful “not to

make their visitations a burden or expense, and to see that the rights

of superiors were maintained, without injury to those of their

subjects.”

In this system a double security was provided for the well-being of the monasteries. The bishops were maintained in their old position as Visitors, and were constituted judges where the conduct of the superior might necessitate the gravest censures. At the same time, by providing that all the monasteries would be visited every three years by monks chosen by the General Chapter and acting in the name of the pope, any failure of the bishop to fulfill his duty as diocesan, or any incapacity on his part to understand the due working of the monastic system, received the needful corrective. One other useful result to the monasteries may be attributed to the regular meetings of General Chapter. It was by the wise provision of these Chapters that members of the monastic Orders received the advantage of a University training. Common colleges were established by their decrees at Oxford and Cambridge, and all superiors were charged to send their most promising students to study and take their degrees in the national Universities. Strangely enough as it may appear to us in these days, even in these colleges the autonomy of the individual Benedictine houses seems to have been scrupulously safeguarded ; and the common college consisted of small houses, in which the students of various monasteries dwelt apart, though attending a common hall and chapel. --192-- In regard to the external

relations of the monastic houses,

a word must be said about their dealings with the parochial churches

appropriated to their use. Either by the

gift of the king or that of some lay patron, many churches to which

they had the right of presentation became united with monasteries, and

a

considerable portion of the parish revenues was applied to the support

of the

religious, to keeping up adequate charity, or “hospitality” as it was

called in the

neighborhood, or other such objects. The

practice of impropriation has been regarded by most writers as a

manifest abuse, and there is no call to attempt to defend it. The

practice was not confined, however, to

the monks, or to the action of lay people were found therein an easy

was to become benefactors of some religious house. Bishops

and other ecclesiastics, as founders of colleges

and hospitals, were quite as ready to increase the revenues of these

establishments in

the same way.

In order that a church might be

legally appropriated to a religious establishment the approval of the

bishop had to be obtained, and the

special reasons for the donation by the lay patron set forth. If these

were considered satisfactory, the

formal permission of the Holy See was, at any rate after the twelfth

century, necessary for the completion of the transaction. The monastery

became the patron of the

benefice thus attached to it, and had to secure that the spiritual

needs of the

parish were properly attended to by the vicars whom they presented to

the cure. These vicars were paid an adequate stipend, usually settled

by episcopal authority.

--193-- Roughly speaking, the present

distinction between a vicarage

and a rectory shows where churches had been appropriated to a religious

house or other pubic body, and where they remained merely parochial.

The vicar was the priest appointed at a fixed stipend by the

corporation which took the rectorial tithes.

It has been calculated that at least a third

part of the tithes of the richest benefices in England were

appropriated either in part of wholly to religious and secular bodies,

such as colleges,

military orders, lay hospitals, gilds, convents ; even deans, cantors,

treasurers, and chancellors of cathedral bodies were also largely

endowed with

rectorial tithes. In this way, at the dissolution

of the religious houses under Henry VIII, the greater tithes of an

immense number of parish churches, now known as vicarages, passed into

the

hands of the noblemen and others who obtained grants of the property of

the

suppressed monasteries.

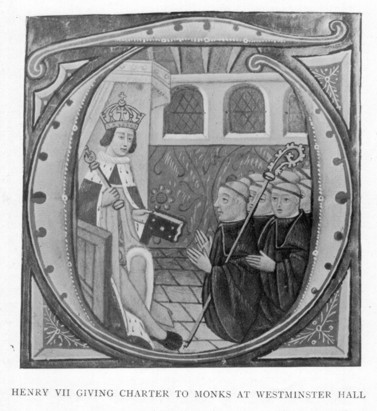

Whilst the impropriation of churches to monastic establishments undoubtedly took money out of the locality for the benefit of the religious, it is but fair to recognize that in many ways the benefit thus obtained was returned with interest. Not only did the monks furnish the ranks of the secular priesthood with youths who had received their early education in the cloister school or at the almonry ; but the churches and vicarages of places impropriated were the special care of the religious. An examination of these churches frequently reveals the fact that the religious bodies did not hesitate to spend large sums of money on the rebuilding and adornment of structures which belonged to them in this way. --194--  > >[Illustration: Henry VII giving charter to monks at Westminster Hall.] [Download 951KB jpg.] --page not numbered-- --blank page, not numbered-- Of many of the religious

houses, especially of the greater

abbeys, the king either was, or came to be considered, the founder. It

has already been pointed out what this

relation to the Crown implied on the part of the monks. Besides this

the Crown could, and in spite of

the protests of those chiefly concerned, frequently, if not ordinarily

did, appoint abbots and other superiors of religious houses members of

the commissions

of peace for the counties in which their establishments were situated.

They were likewise made collectors for grants

and loans to the Crown, especially when the tax was to be levied on

ecclesiastical property ; and according to the extent of their lands

and

possessions, like the lay-holders from the Crown, they had to furnish

soldiers

to fight under the royal standard. In the same way the abbot and other

superiors could be summoned by the

king to Parliament as barons. The number of religious thus

called to the House of Peers at first appears to have depended somewhat

upon

the fancy of the sovereign ; it certainly varied considerably. In 1216,

for example, from the north

province of England eleven abbots and eight

priors, and from the South seventy-one abbots and priors—in all ninety

religious—were summoned to Parliament by Henry III. In 1272 Edward I

called only fifty-seven, mostly abbots, a few, however, being cathedral

priors ; and in later times the number of monastic superiors

in the House of Peers generally included only the twenty-five abbots of

greater houses and the prior of Coventry, and these were accounted as

barons of the kingdom.

--195-- The division of the monastic

revenues between the various

obedientiaries for the support of the burdens of their special offices

was fairly general, at least in the great religious houses. It was for

the benefit of the house, inasmuch

as it left a much smaller revenue to be dealt with by the royal

exchequer at

every vacancy. It served, also, at least one other good purpose. It

brought many

of the religious into contact with the tenants of the monastic estates

and gave them more knowledge of their condition and mode of life ;

whilst the

personal contact, which was possible in a small administration, was

certainly

for the mutual benefit of master and tenant. Since the prior, sacrist,

almoner and other officials all

had to look after the administration of the manors and farms assigned

to their

care, they had to have separate granges and manor-halls. In

these they had to carry out their various duties, and meet their

tenants on occasions, as was the case, for example, at Glastonbury,

where the sacrist had all the tithes of Glastonbury, including West

Pennard, to collect, and had his

special tithe-barn, etc., for the purpose.

Two books, amongst others, The Rentalia et Custumaria of Glastonbury, published by the Somerset Record Society, and the Halmote Rolls of Durham, issued by the Surtees Society, enable any student who may desire to do so to obtain a knowledge of the relations which existed between the monasticlandlords and their tenants. At the great monastery of the West Country the tenure of the land was of all kinds, from the estates held under the obligation of so many knights’ fees, to the poor cottier with an acre or two. Some of the tenants has to find part --196-- of their rent in service, part

in kind, part in payment. Thus, one had to find thirty

salmon, “each as thick as a man’s fist at the tail,” for the use of the

monastery ; some had to find thousands of eels from Sedgemoor

; others, again, so many measures of honey. Some of those who worked

for the monastery or its estates

had fixed wages, as, for example, the gardeners ; others had to be

content with

what was given them.

Mr. Elton, in an appendix to the Glastonbury volume, has analysed the information to be found in its pages, and from this some items of interest maybe given here. A cottier with five acres of arable land paid 4d. less one farthing for rent, and five hens as “kirkset” if he were married. From Michaelmas to Midsummer he was bound to do three days’ labour a week of farm work on the monastic lands, such as toiling on the fallows, winnowing corn, hedging, ditching, and fencing. During the rest of the year, that is, in the harvest time, he had to do five days’ work on the farm, and could be called upon to lend a hand in any kind of occupation, except loading and carting. Like the farmers, he had his allowance of one sheaf of corn for each acre he reaped, and a “laveroc,” or as much grass as he could gather on his hook, for every acre he mowed. Besides this general work he had to bear his share in looking after the vineyard at Glastonbury. Take another example of tenure : one “Golliva of the lake,” held a three-acre tenement. It consisted of a croft of two acres and one acre in the common field. She made a small payment for this ; and for extra work she had three sheaves, measured by a strap kept for that purpose. When she went haymaking she brought her own rake ; --197-- she took her share in all

harvest work, had to winnow a

specified quantity of corn before Christmas, and did odd jobs of all

kinds, such as carrying a writ for the abbot and driving cattle to

Glastonbury.

The smaller cottagers were apparently well treated. A certain Alice, for example, had half an acre field for which she had to bring water to the reapers at the harvest and sharpen their sickles for them. On the whole, though work was plenty and the life no doubt hard, the lot of the Somerset laborer on the Glastonbury estate was not too unpleasant. Of amusements the only one named is the institution of scot-ales, an entertainment which lasted two, or even three days. The lord of the manor might hold three in a year. On the first day, Saturday, the married men and youths came with their pennies and were served three times with ale. On the Sunday the husbands and their wives came ; but if the youths came they had to pay another penny. On the Monday any of them could come if they had paid on other days. On the whole, the manors of the monastery may be said to have been worked as a co-operative farm. The reader of the accounts in this volume may learn of common meals, of breakfasts and luncheons and dinners being prepared ready for those who were at work on the common lands or on the masters’ farming operations. It appears that they met together in the great hall for a common Christmas entertainment. They furnished the great yule-log to burn at the dinner, and each one brought his dish and mug, with a napkin “if he wanted to eat off a cloth” ; and still more curiously, his own contribution of firewood, that his portion of food might be properly cooked. Of even greater interest is the picture of village life led --198-- by monastic tenants which is afforded by the Durham Halmote Rolls. “It is

hardly a figure of speech,”

writes Mr. Booth in the preface to this volume, “to say we have (in

these

Rolls) village life photographed. The dry record of tenures is peopled

by men and women who occupy them,

whose acquaintance we make in these records under the various phases of

village

life. We see them in their tofts surrounded by their crofts, with their

gardens of pot-herbs. We see how they ordered the affairs of the

village when summoned by the bailiff to the vill to consider matters

which affected the common weal of the community. We hear of their

trespasses and wrong doings, and how they

were remedied or punished, or their strifes and contentions and how

they were

repressed, of their attempts, not always ineffective, to grasp the

principle of

co-operation, as shown in their by-laws ; of their relations with the

Prior, who

represented the Convent and alone stood in relation of lord. He

appears always to have dealt with his tenants either in person or

through his officers, with much considerations ; and in the imposition

of fines we find them invariably tempering justice with mercy.”

In fact, as the picture of medieval village life among the tenants of the Durham monastery is displayed in the pages of these Halmote accounts, it would seem almost as if the reader were transported to some Utopia of Dreamland. Many of the points that in these days advanced politicians would desire to see introduced into the village communities of modern England in the way of improved sanitary and social conditions, and to relieve the deadly dullness of country life, were seen in full working order in Durham and Cumberland in pre-Reformation days. Local provisions for public health and general convenience are evidenced by the watchful vigilance of the

--199-- --200--

--page not

numbered--

-end chapter- |

| Historyfish

pages, content, and design copyright (c) Richenda

Fairhurst, 2008 All rights reserved. No commercial permissions are granted. The Historyfish site, as a particular and so unique "expression," is copyright. However, some (most) source material is part of the public domain, and so free of copyright restrictions. Where those sections are not clearly marked, please contact me so I can assist in identifying and separating that material from the Historyfish site as a whole. When using material from this site, please keep author, source, and copyright permissions with this article. Historyfish intends to generate discussion through shared information and does not claim to provide, in any way, formal, legal, or factual advice or information. These pages are opinion only. Opinions shared on historyfish are not necessarily the opinions of historyfish editors, staff, owners or administrators. Always consult proper authorities with questions pertaining to copyrights, property rights, and intellectual property rights. It is my intent to follow copyright law (however impossibly convoluted that may be). Please contact me should any material included here be copyright protected and posted in error. I will remove it from the site. Thank you. |