|

|

Public Domain text

transcribed

and prepared "as is" for HTML and PDF

by Richenda Fairhurst, historyfish.net. November 2007. No commercial permissions granted. Text may contain errors. (Report errors to  ) ) |

CHAPTER

III

The monastic rule, at least

after the days of St. Benedict, was eminently social. Both

in theory and in practice the regular observance of the great abbeys

and other religious houses was based upon the principle of common life.

Monks and other religious were not

solitaries or hermits, but they lived and worked and prayed together in

an

association as close as it is possible to conceive. The community or

corporation was the sole

entity ; individual interests were merged in that of the general body,

and the life of an individual member

was in reality merely an item in the common life of the convent as a

whole. This is practically true in all forms of regular life, without

regard to any variety of observance or rule. Some regulations for

English pre-Reformation houses lay great stress upon this great

principle of monastic life. To emphasise it, they require from all

outward signs of respect for the community as a whole, and especially

at such times and on such occasions as the convent was gathered

together in its

corporate capacity. Should the religious, for example, be passing in

procession, either through the

cloister or elsewhere, anyone meeting them, even where it the superior

himself, was

bound to turn aside to avoid them altogether, or to

--37-- draw on one side and salute

them with a bow as they went by. When the were gathered together for

any public duty no noise of any kind likely to reach their ears was to

be permitted. When the

religious were sitting in the cloister, strangers in the parlour were

to be warned to speak in low tones, and above all to avoid laughter

which might penetrate to them in their seclusion. If the superior was

prevented from taking his meals in the common refectory, he was charged

to acquaint the next in office beforehand, so that the community might

not be kept waiting by expecting him. So, too, the servers, who

remained behind in the refectory after meals were to show their respect

for the community by bowing towards its members, as they passed in

procession before them. For the same reason officials, like the

cellarer, the kitcheners, and the refectorian were bound to see that

all was ready in their

various departments, so that the convent should never be kept waiting

for a meal. In these and numberless other ways monastic regulations

emphasized the respect that must be paid to the community

as a corporate whole.

As the end and object of all forms of religious life was one and the same, the general tenor of that life was practically identical in all religious houses. The main features of the observances were the same, not merely in houses of the same Order, which naturally would be the case, but in every religious establishment irrespective of rule. A comparison of the various Custumals or Consuetudinaries which set forth the details of the religious life in the English houses of various Orders, will show that there is sometimes actual verbal agreement in these directions, even in the case of bodies so different as the Benedictines --38-- and the Cistercians on the one

hand, and the Premonstratensians or White Canons and Canons Regular on

the other. Moreover, where no actual verbal agreement can now be

detected, the rule of life are more than similar

even in minute points of observance. This is, of course, precisely what

anyone possessing a knowledge of the meaning and

object of regular life, especially when the number of the community was

considerable,

would be led to expect. And, it is in this fact which makes it possible

to describe the life led in an English

pre-Reformation monastery in such a was as to present a fairly correct

picture of the life, whether in a Benedictine

or Cistercian abbey, or in a house of Canons Regular, or, with certain

allowances,

in a Franciscan or Dominican friary.

This is true also in respect to convents of women. The life led by these ladies who had dedicated themselves to God in the cloister, was for practical purposes the same as that lived by the monks, with a few necessary exceptions. Its end, and the means by which that end was sought to be obtained, were the same. The abbess, like the abbot, had jurisdiction over the lives of her subjects, and like him she bore a crosier as a symbol of her office and of her rank. She took tithes from churches impropriated to her house, presented the secular vicars to serve the parochial churches, and had all the privileges of a landlord over the temporal estates attached to her abbey. The abbess of Shaftesbury, from instance, at one time, found seven knights' fees for the king's service and held her own manor courts. Wilton, Barking, and Nunnaminster as well as Shaftesbury held of the king by an entire barony, and by the right of this tenure had, for a period, the privilege of being summoned to Parliament. As --39-- regards the interior

arrangements of the house, a convent followed very closely that of a

monastery and

practically what is said of the officials and life of the latter is

true also

of the former.

In order to understand this regular life the inquirer must know something of the offices and position of the various superiors and officials, and must understand the parts, and the disposition of the various parts, of the material buildings in which that life was led. Moreover, he must realize the divisions of the day and the meaning of the regulations, which were intended to control the day's work in general, and in special manner, the ecclesiastical side of it, which occupied so considerable a portion of every conventual day. After the description of the main portion of the monastic buildings given in the last chapter, the reader's attention is now directed to the officials of the monastery and their duties. In most Benedictine and Cistercian houses the superior was an abbot. By the constitution of St. Norbert for his White cannons, in Premonstratensian establishments as in the larger houses of Augustinian, or Black, canons, the head also received the title and dignity of abbot. In English Benedictine monasteries which were attached to cathedral churches, such as Canterbury, Winchester, Durham and elsewhere, the superiors, although hardly inferior in position and dignity to the heads of the great abbeys, were priors. This constitution of cathedrals with monastic chapters was practically peculiar to this country. It had grown up with the life of the church from the days of its first founders, the monastic followers of St. Augustine. No fewer than nine of the old cathedral foundations were Benedictine, whilst one, --40-- longed to the Canons Regular.

Chester, Gloucester, and Peterborough, made into cathedrals by Henry

VIII., were previously Benedictine abbeys.

In the case of these cathedral monasteries the bishop was in many ways regarded as holding the place of the abbot. He was frequently addressed as such, and in some instances at least he exercised a certain limited jurisdiction over the convent and claimed to appoint some of the officials, notably those who had more to do with his cathedral church, like the sacrist and the precentor. Such claims, however, when made were often successfully resisted, like the further claim to appoint the superior, put forward at time by a bishop with a monastic chapter. So far, then, as the practical management of the cathedral monasteries is concerned, the priors ruled with an authority equal to that of an abbot, and whatever legislation applies to the latter would apply equally to the former. The same may be said of the superior of those houses of Canons Regular, and to their bodies, where the chief official was a prior. This will only partially be true in the case of the heads of dependent monasteries, such as Tynemouth, which was a cell of St. Alban's Abbey, and whose superior, although a prior ruling the house with full jurisdiction, was nominated by the abbot of the mother house, and held office not for life, but at his will and pleasure. The same may be said of the priors of Dominican houses, and of the guardians of Franciscan friaries, whose office was temporary ; and of the heads of the alien monasteries, who were dependent to a greater or less extent upon their foreign superiors. Roughly speaking, then, the

office of superior was the same in all religious houses ; and if proper

allowance be

--41-- made for different

circumstances, and for the especial ecclesiastical position necessarily

secured by the

abbatial dignity, any description of the duties and functions of an

abbot in one of the great English houses will be found to apply to

other religious superiors under whatever name they may be designated.

--42--  [Illustration: Thomas, Abbot of St. Alban's] [Download 1,309 KB jpg.] --43-- was chosen. According to the

monastic rule, he was to be

elected by the universal suffrages of his future subjects. In practice

these could be made known in one

of three ways : (I) by individual voting, per viam scrutinii ;

(2) by

the choice of a certain number, or even of one eminent person, to elect

in the name of the community, a mode of election known as electio

per

compromissum ; and (3) by acclamation, or the uncontradicted

declaration of the common wish of the body. Prior, however, to this

formal election there were certain preliminaries to be gone through,

which varied according to circumstances. Very

frequently the founder or patron, who was the descendant of the

original founder of the religious house had to be consulted, and his

leave

obtained for the community to proceed to an election. In the case of

many of the small houses, and,

of course, of the greater monasteries, the sovereign was regarded as

the

founder ; and not unfrequently one condition imposed upon a would-be

founder

for leave to endow a religious house with lands exempt from the

Mortmain Acts,

was that, on the death of the superior, the convent should be bound to

ask

permission from the king to elect his successor. This requirement of a

royal congé d'élire was frequently regarded as an

infringement of the right of the actual

founder, but in practice it appears to have been maintained very

generally in the case

of houses largely endowed with lands, as a legal check upon them,

rendered

fitting by the provision of the Mortmain Acts. Moreover, on the death

of the superior, the king took

possession of the revenues of his office, which were administered by

his officials till,

on the confirmation of his successor, the temporalities were restored

by a royal writ. In some cases this

--44-- administration pertained only

to the portion of the revenues specially assigned to the office of

superior ; in others it appears to have included the entire revenue of

the house, the

community having to look to the royal receiver for the money necessary

for their support.

In practice the process of

election in one of the greater monasteries on the death of the abbot

was as follows. In the first place the community assembled together and

made choice of two of their number to

carry their common letter to the king, to announce the death and to beg

leave to

proceed to the election of a successor. This congé

d'élire was usually granted without

much difficulty, the Crown at the same time appointing the official

charged with guarding the

revenues of the house or office during the vacancy. On the return of

the conventual ambassadors

to their monastery, the day of election was first determined, and

notice to

attend was sent to all the religious not present who were possessed of

what was

called an active voice, or the right of voting, in the election. At the

appointed time, after a Mass De

Spiritu Sancto had been celebrated to beg the help of the Holy

Ghost, the

community assembled in the chapter-house for the process of election.

In the first place was read the constitution of the General Council Quia

propter” in which the conditions of a

valid election were set forth, and all who might be under

ecclesiastical censure or

suspension were warned that they not only had no right to take part in

the

business, but that their votes might render the election null and void.

After this formal preparation the community determined by which of the various legitimate modes of elections they would proceed, either the first or second method being --45-- usually followed. When all this

actual process of election had

been properly carried out and attested in a formal document, the

community accompanied the newly chosen superior in procession to the

church,

where his election was proclaimed to the people, and the Te Deum

was sung. The elect was subsequently taken to the prior's lodgings, or

elsewhere, to await the result of the subsequent

examination as to fitness, and the confirmation. Meantime, if the newly

chosen had been the

acting superior, he could still continue to administer in his office,

but could not hold conventual chapter, or

perform other functions peculiar to the superior, until such time as he

had been confirmed and installed. If he was not the acting superior, he

was required to remain in seclusion, and to

take no part in administrations until after his installation.

Immediately after the process of election had been duly accomplished and the necessary documents had been drawn up, some of the religious were dispatched to the king to obtain his assent to the choice of the community. In the event of this petition being successful, the next step was to obtain confirmation from the ecclesiastical authority, which might either be the bishop of the dioceses, or in the case of exempt houses, the pope. In either case the delegates of the community would have to present a long series of documents to prove that the process had been carried out correctly. First came the royal license to choose ; then the formal appointment of the day of election ; the result of the election, and the method by which it was effected ; the letter signed by the whole community, requesting confirmation of the elect in his office, and sealed by the convent seal ; the royal assent to --46-- the election, and finally an

attested statement of the entire process by which it had been made.

The ecclesiastical authority, upon the reception of these documents, proceeded to an examination of the formal process, and questioned the delegates both as to this, and as to their knowledge of the fitness of the elect for the office. If the result was not satisfactory, the pope or bishop, as the case might be, either cancelled the election or called for the candidate in order to examine him personally as to doctoring and morals, and as to his capability of ruling a religious house in spirituals and temporals. In the event of the elections being quashed, the authority either ordered a new election, or, on the ground of the failure of the community to elect within a definite period a fit and proper superior, appointed someone to the office. The ecclesiastical confirmation of the election was followed, after as brief an interval as possible, by the installation. In the case of an exempt abbey, a delay of some weeks was inevitable, sometimes until the return of messengers from the Curia, and thus occasionally the office of superior was necessarily kept a long time vacant. If the superior was to hold the abbatial dignity, before his installation he received the rite of solemn benediction at the hands of the diocesan. This was generally conferred in some other than the monastic church, probably because until after installation, which was subsequent to the abbatial blessing, the new abbot was not supposed legally to have any position in the house he was afterwards to rule. On the day appointed for the solemn installation, the abbot, walking with bare feet, presented himself at the church door. He was there met by the community and --47-- conducted to the High

Altar,where, during the singing of the Te Deum, he remained

prostrate

on the ground. At the conclusion of the hymn,he was conducted to his

seat, the process of his election and

confirmation was read, together with the Episcopal or papal mandate,

charging all the religious

to render him every canonical obedience and service. Then one by one

the community came, and,

kneeling before their new superior, received from him the kiss of

peace. The ceremony was concluded by a solemn

blessing bestowed by the newly installed abbot standing at the High

Altar.

The position of the abbot among his community may be summed up in the expression made use of by St. Benedict. He takes Christ's place. All the exterior respect shown to him, which to modern ideas may perhaps seem exaggerated, if not ridiculous, presupposes this idea as existing in the mind of the religious. Just as the great Patriarch of Western monachism ordered that obedience was to be shown to a superior as if it were obedience paid to God himself, and as if the command had come from God, so reverence and respect was paid him for Christ's love, because as abbot "father" he was the representative of Christ in the midst of the brethren. In all places, for this reason, external honour was to be shown to him. When he passed by, all were to stand and bow towards him. In chapter and refectory none might sit in their places until he had taken his seat ; when he was in the cloister no one might take the seat next to him, unless he invited him so to do. In his presence conversation was to be moderated and unobtrusive, and no one might break in upon anything that he might be saying with remarks of his own. Familiarity with him was to be --48-- avoided, as it would be with

our Lord himself ; and he, on his part, must be careful not to lower

the

dignity of his office by too much condescending to those who might be

disposed to

take advantage of his good nature ; nor might he omit to correct any

want of

respect manifested towards his person. He was in this to consider his

office and not his natural inclinations.

The abbot is to occupy the first place in the choir on the right-hand side. During the Office his stall is to be furthest from the altar, the juniors being in front of him, and placed nearest to the sanctuary steps. At Mass, however, the position is changed, the abbot and seniors being closest to the altar, for the purpose of making the oblations at the Holy Sacrifice, and giving the blessings. Whenever a book or other thing is brought to him, the book and his hand are to be kissed. When he gives out an Antiphon, or sings a Responsory, he does so, not as the others perform the duty in the middle of the choir, but at his own stall ; and the precentor, coming with the other cantors and his chaplain, stand round about him to help him, if need be, and to show him honour. When the abbot makes a mistake and, according to religious custom, stoops to touch the ground as a penance, those near about him rise and bow to him, as if to prevent him in this act of humiliation. He reads the Gospel at Matins, the Sacred Text and lights being brought to him. He gives the blessings whenever he is present, and at Mass he puts the incense into the thurible for the priest, and blesses it ; gives the blessing to the deacon before the Gospel, and kisses the book after it has been sung. The altar, at which he offers the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, is to be better ornamented than the other altars, --49-- and he is to have more lights

to burn upon it during the Holy Sacrifice. If

his name is mentioned in any list of duties all bow on hearing it

read out in the Chapter, and they do the same when he orders any

prayers to be said or any duty to be performed, even should he not be

present when the order is published.

The whole government of every religious house depended upon the abbot, as described by St. Benedict in the second chapter of his Rule. He was the mainspring of the entire machine, and his will in all things was supreme. His permission was required in all cases. All the officials, from the prior onward, were appointed by him, and had their authority from him : they were his assistants in the government of the house. In the refectory he alone could send from anything, and could allow anyone to be admitted to the common table. The meal was not to begin till after the reading had commenced and hehad given the sign to the refectorian to ring the signal-bell. He might send a dish to any one of the brethren whom he thought stood in need of it, and the brother on receiving it was to rise and bow his acknowledgement. In early times the abbot slept in he common dormitory in the midst of the monks. His duty it was to ring the bell for the community to rise ; and, indeed, when any ringing was required for a public duty, he either himself rang the call, or stood by the side of the ringer till all were assembled for the duty, and he gave the sign to cease the signal. To emphasise this part of this duty, in some Orders, at the abbot's installation the ropes of the church bells were placed in his hands. It was naturally the abbot's place to entertain the guests that came to the monastery, and he frequently had to have his meals --50-- served in his private hall. To

these repasts he could, if he wished,

invite some of the brethren, giving notice of this to the superior who

was to preside in his place in the refectory. On great days in some

houses, like St. Mary's, York, after

the abbot had been celebrating the Office and Mass in full pontificals,

it was the

custom for him to send his chaplain to the door of the refectory to ask

the sacred

ministers who had served him, with the precentor and the organists, to

dine with him.

When the abbot had been away from the monastery for more than three days it was the custom for the brethren to kneel for his blessing and kiss his hand the first time they met him after his return. When business had taken him to the Roman Curia or elsewhere, for any length of time, on his home-coming he was met in solemn procession by the entire community who, having presented him with holy water, were sprinkled, in their turn, by him. They conducted him to the High Altar, chanting the Te Deum for his safe return, and received his solemn blessing. Whilst all reverence was directed to be given to him, he on his part was warned by the Rule and by every declaration, that he must always remember the fact that all this honour was paid not to him personally, but to his office and to Christ who was regarded and reverenced in him. He, above all others, was to be careful to keep every rule and regulation, since it was certain that where he did not obey himself, he could not look for the obedience of others ; and that though he had no one set over him, he was, for that reason, all the more bound to claustral discipline. As superior, he had to stand aloof from the --51-- rest, so as not unduly to

encourage familiarity in his subjects. He

was to show no respect for persons ; not favouring one of his sons more

than

another, as this could not fail to be fatal to true observance and to

religious

obedience. In giving help he should be a father, says one Custumal ; in

giving instruction, he should speak

as a teacher. He should be ever ready to help those who are striving

after the higher paths of virtue. He should not hesitate to stimulate

the indifferent to earnestness, and to use ever means to rouse the

slothful. To him specially the sick are committed, that

he may by his visits console and strengthen him to bear the trials God

has sent them.

He must, in a word, study with paternal solicitude the character, actions, and needs of all the brethren ; never forgetting that he will one day have to render to God an account of them all. The prior, or second superior

of the house, is above all things concerned with the observance and

internal discipline of the monastery. He is appointed by the abbot

after hearing the opinions of the seniors. Sometimes, as at Westminster

and St. Augustine's, Canterbury, he was chosen with great deliberation.

In the first place, three names were selected by the

precentor and by each of the two divisions of the house, the abbot's

side of the choir and the

prior's side. These selected names were then considered by a committee

of three appointed by the abbot, who

reported their opinion to him. Finally, the abbot appointed whom he

pleased.

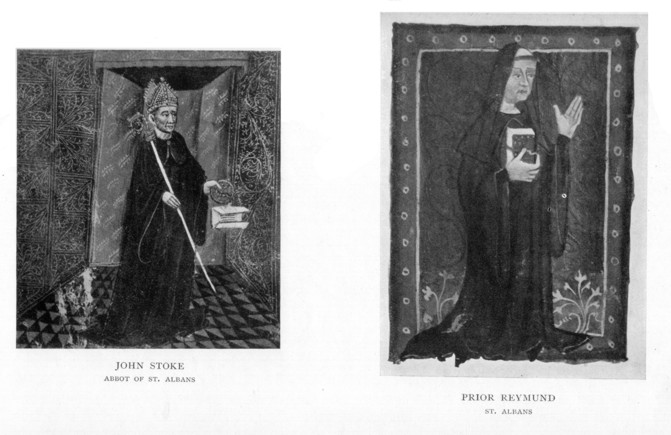

In all places and duties the prior's place is next after the --52--  [Plate: John Stoke, Abbot of St. Albans. Prior Reymund, St. Albans.] [Download 630KB jpg, John Stoke.] [Download 670 jpg, Prior Reymund.] --page not numbered--- --blank page, not numbered-- abbot. He is to be honoured by

all ; when he enters the Chapter or comes to the Collation, all rise

and continue standing

until he has sat down ; when the community are incensed in choir, he is

to have that

mark of respect paid to him, next after the priest who is vested in a

cope. The prior, says one Custumal,

ought to be humble, kindly in disposition, a living example of

religious

observance, excellent in everything, doing all things like the rest of

the

brethren. He should be first among the first, and last with the last.

The reader will perhaps here recall Jocelin of Brakelond's analysis of the reasons which prompted the choice of Prior Herbert at Bury, in the closing years of Abbot Sampson's rule : "The chapter

being over, I being the guest-master, says Jocelin, sat in the porch

of the Guest-hall, stupefied, and revolving in my mind the things I had

heard

and seen ; and I began to consider closely for what cause and for want

particular merits uch a man should be advanced to so high a dignity.

And I began to reflect that the man is of comely

stature and of (good) personal appearance ; a man of handsome face and

amiable

aspect ; always in good temper ; of a smiling countenance, be it early

or late

; kind to all ; a man calm in his bearing and grave in his demeanour ;

pleasant

in speech, possessing a sweet voice in chanting and impressive in

reading ;

young, brave, of healthy body, and always in readiness to undergo

travail for

the need of the church ; skilful in conforming himself to every

circumstance of

place and time, either with ecclesiastics or laymen ; liberal and

social, and

gentle in reproof ; not spiteful, not suspicious, not covetous, not

drawling,

not slothful ; sober and fluent of tongue in the French idiom, as being

a

Norman by birth ; a man of moderate capacity whom if too much learning

should

make (one) mad, might be said to be a perfectly accomplished man."

--53-- The prior's main duty, besides

taking the abbot's place whenever he was absent, and generally looking

after

the government of the monastery, was to see to the discipline of the

house and to

maintain the general excellence of observance. This he was to do as

much by example as by precept, and he

was to make himself loved rather than feared. He was told to endeavour

to occupy in a community, what is called in one rule,

the position of the mother of the family. He stood, as it were, between

the father and his sons ;

and so long as discipline was not harmed, he should not hesitate to be

prodigal in kindness and

ready to open his heart in friendly intercourse with all who sought his

help.

Let him remember, says one rule, that the peace of the house depends on

him.

In monasteries where no other disposition was made, after the triple prayer before the night Office has been said, it was the prior's duty to take a lighted lantern and go first to the dormitory to see that all were up an d that none had overslept themselves, and then to perambulate [walk around] the cloister and the chapels to see that no one had fallen asleep there, and that the altars were ready for Mass. After Compline at night, having given the sign for leaving the church, he himself went out first, and after receiving the holy water at the door from the hebdomadarian, or priest appointed for the weekly duty, stood aside whilst the community filed out into the cloister, and each in their turn, after being sprinkled with the hold water, put on his hood and passed up to the dormitory. When all were gone, the prior was directed to go round the house and cloister, with a lantern in necessary, to see that all the doors were fastened, that the lights were safe --54-- for the night, and that all was

well and quiet in the time of great silence. He

then took the keys of the outer doors with him to the dormitory, and

sitting by his bed, waited to retire until all the rest were lying

down.

The prior had his regular week for acting as hebdomadarian priest like the rest ; but he did not take his turn with the others in reading in the refectory or serving at the meals. When he passed along the cloister the brethren were not bound to rise and bow as they had to do to the abbot ; but should he wish to sit down anywhere, those near the place were to rise and remain standing until he was seated. As his office was chiefly concerned with the regular discipline, all permissions to be absent from conventual duties, even if granted by the abbot himself, were to be notified to him. A true prior, it is frequently remarked in the old Custumals, is a blessing to a religious house, and his presence is like that of an angel of peace. "He should

show, says one English writer, an example of the patience of holy Job

and of

the devotion of David. To his subjects he should manifest the religious

observance of our holy fathers, so

that he, who is first in name, may be ever first in the virtues of

patience,

devotion, and, indeed, in all the virtues of the religious life."

The sub-prior was the prior's

assistant in the duties of his office. Like

the rest of the monastic officials, he was appointed by the abbot

with the advice of the prior. Ordinarily this third superior did not

take any special position in the community. He usually occupied the

--55-- place of his profession except

when he was called upon to preside over the religious exercises instead

of the abbot or prior. All the duties which had to be performed by the

prior, in his absence devolved upon the

sub-prior.

Besides this, the sub-prior was often charged with specially looking to certain matters of discipline, and with giving certain permissions, even when the prior was present. All permissions given and arrangements made by the sub-prior, during the absence of either the abbot or prior, were to be reported to them on their return to claustral duties. The sub-prior should be remarkable for his holiness, says one English writer, his charity should be overflowing, his sympathy should be abundant. He must be careful to extirpate evil tendencies, to be unwearied in his duties, and tender to those in trouble. In a word, he should set before all the example of our Lord." Besides the prior and

sub-prior, in most large monasteries there were third and fourth

priors, called

also circas or circatores claustri,

that is, watchers over the discipline of the cloister. Their duty

chiefly consisted in going round

about the house and specially the cloister in times of silence, to see

that

there was nothing amiss or contrary to the usual observance. They had

no authority to correct, but they

kept their eyes and ears open in order to report. They did not go about

necessarily together,

but according as special duties might have been assigned to them by the

abbot. When, in the course of their official investigations, they found

any of the brethren engaged in

conversation or work out of the ordinary

--56-- course, it was the duty of one

of those so engaged to inform the official of the permission they had

received. The usual time for the exercise of their functions was after

Compline, before Matins, after

dinner and supper, and whenever the community were gathered together in

the cloister.

--57-- -end chapter- |

| Historyfish

pages, content, and design copyright (c) Richenda

Fairhurst, 2008 All rights reserved. No commercial permissions are granted. The Historyfish site, as a particular and so unique "expression," is copyright. However, some (most) source material is part of the public domain, and so free of copyright restrictions. Where those sections are not clearly marked, please contact me so I can assist in identifying and separating that material from the Historyfish site as a whole. When using material from this site, please keep author, source, and copyright permissions with this article. Historyfish intends to generate discussion through shared information and does not claim to provide, in any way, formal, legal, or factual advice or information. These pages are opinion only. Opinions shared on historyfish are not necessarily the opinions of historyfish editors, staff, owners or administrators. Always consult proper authorities with questions pertaining to copyrights, property rights, and intellectual property rights. It is my intent to follow copyright law (however impossibly convoluted that may be). Please contact me should any material included here be copyright protected and posted in error. I will remove it from the site. Thank you. |