|

|

Public Domain text

transcribed

and prepared "as is" for HTML and PDF

by Richenda Fairhurst, historyfish.net. September 2007. No commercial permissions granted. Text may contain errors. (Report errors to  |

|

CHAPTER I GENERAL

REMARKS ON

SHRINES The saints’

shrines in England

were famous throughout Christendom ; for the people of this land

sacrificed of

their substance to honour their saints, whose virtues shone

pre-eminently

thought-out the whole Christian world, and attracted the devotion of

countless

pilgrim from abroad, in addition to those within her own borders. Not

only in

The greed of Henry VIII

caused him to covet the riches of the accumulated offerings of

centuries ; and

his despotic disposition could not brook that others—even though in

--1--

share the honour and reverence which he considered due only to his own august person. It was no question of religion with him which made him withhold the donations he once lavished on shrines and prompted him to commit the most overwhelming system of sacrilege. It was truly a Reign of Terror for the “religious,” either in the technical or common sense, and the destruction, both moral and structural, was so vast that when the nation could again breathe without fear of the gibbet, true religion was not a conspicuous virtue in the breasts of her children. A compulsory hypocrisy forced upon them by a hypocritical tyrant had become too ingrained to be lightly cast away. And if the spirit, or will, survived to restore the desecrated shines, in however humble a manner, the very essence had gone, the relics were in the most cases irrecoverably lost. They had been burnt, scattered, and defiled—as it were, again martyred as witnesses for their Lord ; for in those relics were enshrined the principles which actuated the saints in life, of Christian charity and humility, and of boldness in the defense of those things which were God’s. Yet Caesar coveted all ; he was his own god, and as the Roman Emperors of old deified their predecessors, and themselves, so Henry the Eighth thrust himself before the nation as the only legitimate being to receive the offering of the incense of homage. In the following pages are occasional quotation from the King’s State papers, and in them the real motives by which he was prompted in this reforms are more clearly apparent than can be conveyed by modern pen. The principal

instruction is for the spoils to be conveyed to the royal treasury in

the

The subject of

relics cannot be

considered here, except for far as it affects the form and decoration

of the

shrine and the position they occupied in the sanctuary. The practice of

building

Christian altars over the relics of martyrs obtained from the Book of

the

Apocalypse ; “I saw under the altar the souls of them that were slain

for the

word of God, and for the testimony which they held.” The earliest

examples of this use

of martyrs’ tombs

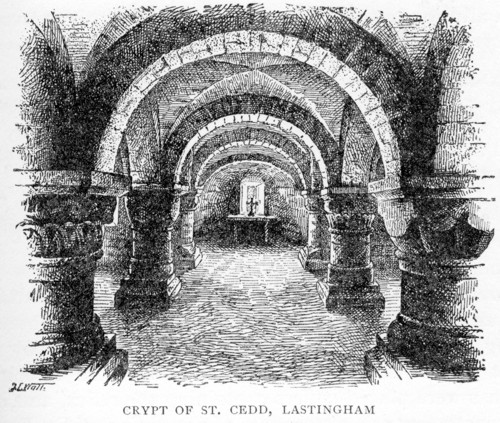

Such altars became the shrines of those saints, and the custom yet pertains to Western Christendom --3-- The

same idea prevails where a casket containing relics is

placed within

an open altar, as in the case in the ancient

“One might see

whole cities running to the

monuments of martyrs,” and “apostles in their death were more honorable

than

the greatest kings upon earth ; for even at Rome, the royal city,

emperors and

consuls and generals left all and ran to the sepulchers of the

fisherman and

tent-maker.” The shrine of

chapel thus built was early known as a

martyry.2 The tombs, or

shrines, of those saints

which were not covered by an altar ofttimes assumed lofty proportions,

and as

art increased they became things of great beauty, being built of marble

and

alabaster, decorated by the most skilled sculptors. On some of these

structural

shrines were placed covers containing the relics, and in a

thirteenth-century

restoration of the shrine of St. Egwin at Evesham Abbey the stone

shrine on

which the coffer was exalted is called a throne.3

The portable

coffer—a coffin or smaller chest—was called a feretrum,

or bier, capable of being

borne in procession.

It contained either the whole body of the saint, as was the case with St. Cuthbert and St. Edward the Confessor, or part of the relics, in this case of --blank page--  The smaller feretories were used when, in a translation of the relics, the body was found to have perished and the bones only were preserved, which would naturally occupy only a small compass. Another reason for the use of a small feretory was occasioned by the division of relics. This division could easily be effected with dry bones, which were frequently distributed among various religious houses ; but it was also done by the severance of a limb or member from the otherwise perfect body. The Eastern Church seems to have been the first to dismember bodies for this purpose. Such and action, at once

revolting

and sacrilegious, encouraged the coveting and thieving of relics, and

that

trafficking in fragments of saints, which led to much scandal during

the Middle

Ages. The

magnificence of many of the

feretories may be gathered from the description of some of these which

formerly

enriched the churches in

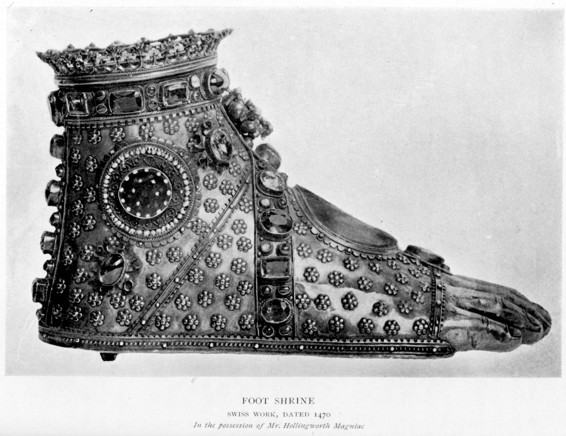

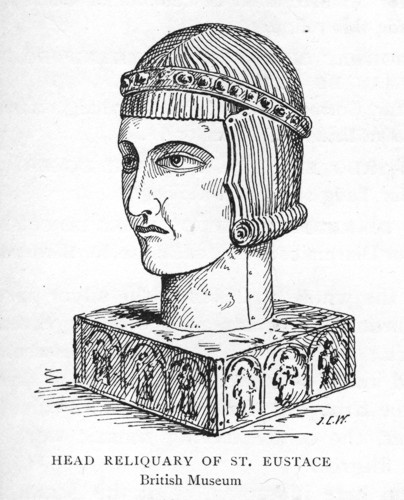

Those of the greatest renown will be described in their respective places, but many of the smaller, which were preserved in the treasuries or around the principal shrine, must have been of great beauty, and the description of one of the many kept at Lincoln indicated the art which was lavished upon them :— made in goldsmith’s work, which contained a fragment of the corresponding part of the saint’s body. When it took the form of a head it was frequently called a chef. The earliest known head is of St. Candidus in the Another chef in the Among them was a head of silver gilt standing upon a foot of copper gilt, having a garland with stones of divers colours, which contained relics of the eleven thousand virgin companions of St. Ursula ; but this class of shrine which existed in England has entirely perished. The shrine of St. Osyth’s arm at  [Illustration: Plate II,

the Chef, or head shrine of St. Peter.]

[Download 3,044KB jpg.]

--page not numbered-- An

arm of St. Mellitus was given by the monks of

[Illustration: Head reliquary of St. Eustace.] [Download 651KB jpg.]

of St. Richard

in a silver-gilt

case held up by two angels.

The shrine of St. Lachtin’s arm which was preserved in St. Lactin’s Church, Donoughmore, The upper end of the arm is also ornamented with silver and a --7-- row of bluish-grey stones resembling the chalcedony, and there are indications of a second row of stones above. Riveted across the centre of the arm is a broad band with knots in relief, and down the arm are four flat narrow fillets at equal distances, inscribed in Irish minuscules :— 1.MAELSECHNAILL UCELLACHAIN DO ARDRIG. . . INGI IN CUMTACHS (Pray for

Maelsechnaill descendant of Cellachan . . . who made this reliquary.)

2. DO CHORMAC MAC MEIC CARTHAIGI DO RIG DAMNU MUMAN DO RATHAE. . . D . . . D (Pray for Cormac son of MacCarthaig, namely, for the Crown Prince of Nunster. . . ) 3. OR DO TADG MAC ME . . . THIGI DO RIG . . . (Pray for Tadg son of . . . King . . . ) 4. OR DO DIARMAIT MAC MEIC DENISC DO COMARBA DIDOM (Pray for Diarmait son of MacDenisc, for the successor of . . . ) Nearly the

whole of the arm, the

silver parts as well as those of bronze, is ornamented with engraved

knots and

scroll-work ; and at the upper part between

the aforementioned rows of stones are figures of

animals. The root of the arm was fastened

by a

circular cap, inlaid with silver, the centre having mosaic work

surrounded by

silver filigree.

The arm here illustrated is in the are long and

straight ; most of them have the hand opened in

benediction,

though some are entirely closed in the same way as St. Lachtin’s. The

Fiocail

Phadraig, or shrine

of St. Patrick’s tooth—fourteenth century—is inscribed in Lombardic

capitals

“Corp Naomh,” the Holy Body. It has

small plates

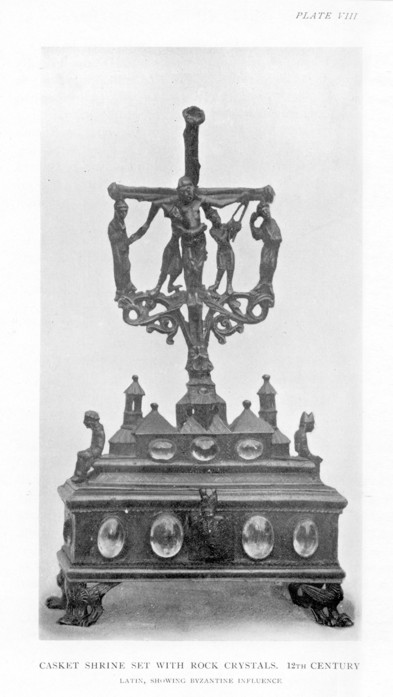

--8--  [Illustration: Plate

III Shrine of

[Download 1,900KB jpg.] --page not numbered-- --blank page--  [Illustration: Reliquary arm.]

This

description of reliquary has

led in recent times to many undeserved charges of fraud.

That there should be numerous arms or heads of the same saint offers the opportunity for the uninitiated to make such charges, for which occasionally there may be some foundation ; but when it is understood that an “arm of St. Oswald” or a “head of St. Thomas” has from long custom applied to a reliquary fashioned to that form, and containing, it may be, the merest fragment of a bone from that part of the saint’s body, and with no fraudulent intent called “the arm” or “the head” of Saint So-and-so, there need by no surprise at a saint possessing arms or heads in many different localities. --9--

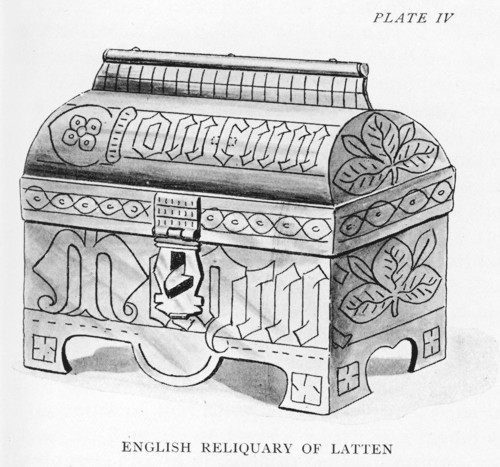

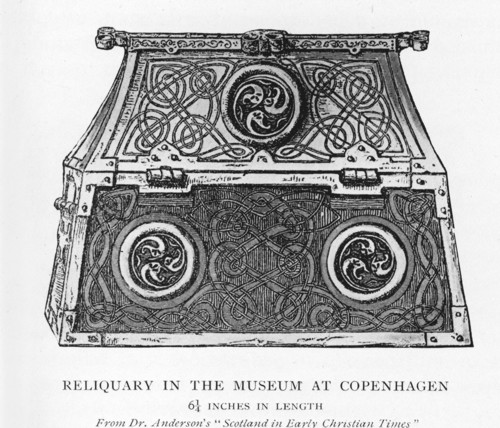

The usual form

of Celtic

reliquary, at one time so numerous in Ireland,

is a quadrangular metal box with the sides inclined inwards and with a

cover

like a gabled roof, under which shape the Temple

of Jerusalem is represented

in the

Book of Kells.

These coffers were decorated with enameling and chasing, exhibiting a great degree of art, barbaric perhaps, but in a spirit unsurpassed in later times. Dr. Petrie concludes from the number of references to shrines in the Irish annals that, previously to the irruption of the Northmen in the eighth and ninth centuries, there were few, if any, of the distinguished churches in Ireland which were not possessed of costly shines. At

the same time it must be borne in mind that in Ireland

these were not always made to contain the corporeal relics of the

saints, but

were made for the preservation of such relics of holy people as their

bells,

books or the gospels, and things of personal use, such as the shoe of

St.

Bridget. The museums of Denmark

contain many spoils of Celtic workmanship which were seized by the

Danish

raiders who were for ages the scourge of our coasts. A few of these

Celtic shrines are

happily left to us—the Breac Moedog, or shrine of St. Moedoc of Ferns

(see page

81) ; and of St. Manchan in the chapel of Boher, Lemanaghan,

King’s

County

(page 84).

One which was found in the river Shannon is now in the museum of antiquities in Edinburgh ; another is preserved in Monymusk House in Aberdeenshire ; and another in the Royal Irish Academy. An Irish reliquary found in Norway, and now in the museum at Copenhagen, is inscribed in runes. Similar little caskets of brass, of English make, may be seen in the English museums, but the workmanship in much inferior to those of Ireland. Coffers of similar form and beautifully decorated with Limoges enamels were at one time fairly common --10--

[Illustration:

Plate IV Reliquaries.]

[Download 950KB jpg, Latten.] [Download 950KB jpg, Copenhagen.] --page not numbered-- --blank page-- throughout England

; examples still exist at Hereford

and in the museum of the Society of Antiquaries. These

are of Romanesque character ; but in

the Middle Ages reliquaries assumed architectural forms ; imitations of

churches in miniature, which old inventories reveal, were numerous

throughout

this country. All English examples,

however, of this character seem to be totally lost. But it was

the earlier form of casket shrine

which was generally used—though greatly elaborated—in the feretories of

the great

continental shrines.

One of the most

beautiful of these portable shrines made for a British saint is the

châsse of

St. Ursula, preserved in the Hospital

of St. John at Bruges,

in which the chief beauty is not of gold or silver or gems, but the

exquisite

miniature paintings of Hans Memling (Plates XIV and XV).

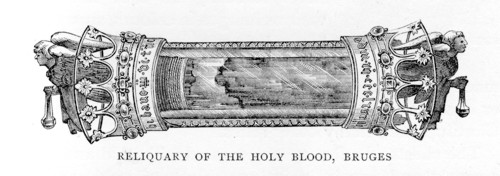

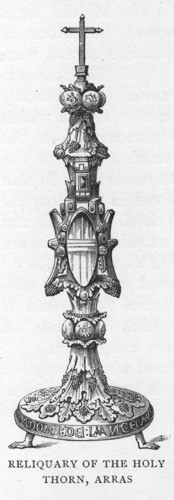

Sometimes the emblem of a saint was made as a reliquary for the relics of that saint, as that of St. Ursula in the church of St. Antonio at Padua, which is a model of a perfectly rigged ship, in allusion to her emigration. In addition to those already mentioned were numerous smaller reliquaries of various designs, which became common during the latter Medieval and Renaissance

[Illustration: Reliquary of the Holy Blood, Bruges.] Ages, such as phylacteries, ampulles, tabernacles, images, chests, caskets, glass-domed roundels, crystal cylinders, and others similar to a monstrance or ostensorium, each of which were mounted or supported in metal work according to their individual requirements. For extant examples of these reliquaries we must look --11-- in the museums at home and the churches abroad ; but the Lincoln inventories contain vivid descriptions of many of those which formerly existed in that cathedral church. “Item, one phylatorye of Cristall stonding upon iiij feet in playne sole sylver and gylte having a pinnacle in the hegth contenyng the toth of saynt hugh, weying with the contents ij unces.” “Item,

one Ampulle of crystal with a foot and

covering of silver partly gilt, containing the relics of St. Edmund the

Archbishop.” These small

reliquaries were

frequently arranged in a Reliquary Table, or Tabernacle, the doors of

which

were opened for their exposition ; and in Henry the Eighth’s

injunctions for

the destruction of shrines these tables are often mentioned.

[Illustration:

Reliquary of the Holy thorn, Arras.] Lincoln

possessed a tabernacle of silver standing on four lions with various

images in

colours, surmounted by the holy rood and attendant figures, elaborately

jeweled, besides many made of wood. “Item,

one

fayre Chyste --12-- [Illustration:

Plate V

Monstrance Reliquary of the finger

of St. Mary Magdelen.] --page not

numbered-- --blank page-- A foreign

example must again

illustrate the lost treasures of England.

The thirteenth-century chest containing the hair-cloths of St.

Louis is of wood, covered with metal and painted

with

heraldic designs and allegorical [Illustration:

Table of Relics, Mons]

The

use of these chests will be understood if it be borne in mind that many

of the

reliquaries were put away, only to be exposed on certain festivals ;

while

others, which were daily exhibited and were small enough to be removed,

were

nightly placed in the chests for safety. This

would be necessary in a church possessing a great

number of

reliquaries—e.g. the cathedral of

Canterbury, of which Erasmus said that the exhibitions of relics seemed

likely

to last for ever, they were so numerous ; and his testimony is borne

out by the

inventory contained in one of the cartularies of Christchurch,4

which enumerates no fewer than

four hundred items.

It commences with a

list of twelve bodies of saints—Sts. Thomas, Elphege, Dunstan, Odo,

Wilfrid,

Anslem, Aelfric, Blosi, Audoeni, Selvi, Wulgan, and Swithun.

Eleven arms in jeweled silver-gilt

shrines—Sts. Simeon, Blase, Bartholemew, George

--13--

And three heads— “The

head of St. Blasé in a silver

head gilded, [Illustration: Relic Chest of St. Louis] Some of the

movable feretra also

contained an accumulation the relics of many saints. The most memorable

instances are to be found

in the Canterbury

inventories.5 One

such example will suffice :— In

a chest of ivory with a crucifix --14--

--page not

numbered-- --blank page--

Item,

a bone of

blessed Leo, pope and confessor. --15--

Item,

a

rib of the

blessed Appollinaris,

martyr, with one

tooth of the same. Pendant or

pectoral reliquaries

were in use at an early period throughout Christendom. Some were made

to contain the consecrated Host,

but others enclosed relics of the saints, and were worn as amulets. --16--

[Illustration:

Plate

VII Ampulla, or Phial Reliquary.] --page not

numbered-- --blank page--

describes as of

silver, chased

and jewelled, divided into compartments and inscribed with names.

These, however, did not always contain relics

of the body, but some times a fragment of some object associated with

the

saint. One of the

reliquaries mentioned

in the will of Perpetuus, Bishop of Tours,6 was of this type

:—

“To

thee, most dear Euphronius, brother and

bishop, I give and bequeath my silver reliquary. I

mean that which I have been accustomed to

carry upon my person, for the reliquary of gold, which is in my

treasury,

another two golden chalices, and cross of gold, made by Mabuinus, do I

give and

bequeath to my church.”

A pendant

reliquary—a small

silver skull—was found in 1829, whilst ploughing a field, which was

formerly

part of the ground of the abbey of Abingdon ; and another of silver,

suspended

on a silver chain round the neck of a skeleton, was found in the

churchyard of

St. Dunstan’s, Fleet Street, London, during the demolition of the old

church in

1831. It is figured in the Archaeological

Journal, vol v. where its

dimensions are given as 2 ¼ inches in diameter and half an inch

thick. On one side is represented St.

George, and on

the other the British St. Helen.

At

the

top is a small aperture, through which to pass the relic, and which is

closed

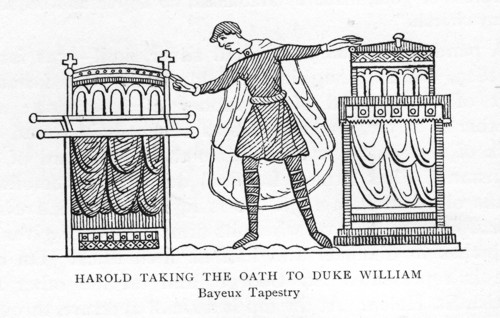

by a movable shutter of the same metal. In Battle Abbey

there was a

superb reliquary shaped like an altar, given by William I., which had

been used

by him for military Mass in the field, and which had accompanied his

troops in

their conquest of England.

Possibly this was one of the

two shrines

represented in the Bayeux

tapestry

whereon Harold, when William’s prisoner in Normandy,

was compelled to take an oath to support the duke’s pretensions to the

English

throne before he could regain his liberty.

--17-- placed on a draped pedestal ; while the other appears to form part of a vested altar, and is probably that which was given to Battle Abbey. Few names have been left to us of those who designed and fashioned these shrines and precious feretories of gold and silver. One such artist, Anketill, had been brought up as a goldsmith. He had passed seven years in superintending the royal mint in Denmark and in making curious articles for the Danish king, but returning  Illustration: Harold taking the oath to England he became a professed brother in the monastery at St. Albans. There he made the feretrum of St. Alban, shrines for the relics of Sts. Bartholomew, Ignatius, Laurence, and Nigasius, and many articles of church furniture—thuribles, navets, and elaborate candlesticks. Another from the same abbey undertook a similar work at Canterbury, not only as a worker in metals, but also as a designer, for we are told that the shrine of St. Thomas was the work of that incomparable official Walter de Colchester, sacrist of St. Albans, assisted by Elias de Dereham, canon of Salisbury. --18-- --blank page--  [Illustration: Plate VIII Casket Shrine.] [Download 3,547KB jpg.] --page not numbered-- Footnotes: 1. Canon 83, Codex Can. Eccl. Afric. A.D. in Brun’s Canones, i. 176 2. Dugdale’s Monasticon, vol. ii. 3. Lincoln Inventory. 4. Cotton . MS., Galba, E., iv. 5. Inventories of Christchurch, Canterbury, by J. Wickham Legg and W. H. St. John Hope. 6. Circa 477. -end

first half of

Chapter One [division, mine]- |

| Historyfish pages,

content, and design copyright (c) Richenda

Fairhurst, 2008 All rights reserved. No commercial permissions are granted. The Historyfish site, as a particular and so unique "expression," is copyright. However, some (most) source material is part of the public domain, and so free of copyright restrictions. Where those sections are not clearly marked, please contact me so I can assist in identifying and separating that material from the Historyfish site as a whole. When using material from this site, please keep author, source, and copyright permissions with this article. Historyfish intends to generate discussion through shared information and does not claim to provide, in any way, formal, legal, or factual advice or information. These pages are opinion only. Opinions shared on historyfish are not necessarily the opinions of historyfish editors, staff, owners or administrators. Always consult proper authorities with questions pertaining to copyrights, property rights, and intellectual property rights. It is my intent to follow copyright law (however impossibly convoluted that may be). Please contact me should any material included here be copyright protected and posted in error. I will remove it from the site. Thank you. |