|

|

Public Domain text

transcribed

and prepared "as is" for HTML and PDF

by Richenda Fairhurst, historyfish.net. March 2008. No commercial permissions granted. Text may contain errors. (Report errors to  |

|

CHAPTER II Of all British

shrines St.

Alban’s demands primary consideration, not only as that of When the persecution of Diocletian ceased, a small chapel is said to have been built over St. Alban’s grave on the top of a hill situated to the north of Verulam city. At the invasion of the Saxons in the sixth century this chapel was ruined, and during the two hundred years of paganism which followed, the grave of St. Alban was forgotten. Owing to a

vision of the Mercian

king Offa (so runs the story), in which he was admonished to search for

the

martyr’s body and exalt it to a place of honour, a monastery was

founded and

the relics of St. Alban were placed in a shrine in 795.

It was only a simple monument, but it excited

the covetousness of the semi-Christian Danish invaders, who, intent on

plunder,

broke it open and carried off the relics to By strategy the relics were restored to their own church. --35-- The sacrist of The ambition of

many succeeding

abbots was to make a shrine worthy of Such a treasure the monks of Ely were loth to part with, but the St. Albans fraternity understood that weakness—the coveting of relics—and had, as we have seen, made provision for its occurrence ; at the same time spreading abroad the report of their removal, thus hoping to hoodwink the Danes and escape their ravages. When all fear

was past, the

precaution of the --36-- of their patron stain. Those bones sent from Ely were deposited in a wooden chest, in which St. Alban had been laid in the time of Offa, and in future years that also came to be venerated in consequence of its former association with the martyr. At last Abbot Geoffrey ordered the work of the shrine to be again taken in hand. The copper was overlaid with plates of beaten gold. Sixty pounds 1 had already been spent on the feretory, when famine again impoverished the country, and the precious metal were stripped off for the benefit of the starving. This was the year 1128, but the following year was one of plenty, and the long-delayed work was accomplished. It was made by Monk Anketill who had been a goldsmith before joining the brethren, was of silver gilt, and decorated with a profusion of gems ; but the upper-most crest was not finished, as they had not collected a sufficiency of jewels. Scarcely was it completed before it was again destroyed, not to relieve the starving poor this time, but to buy the manor of Brentfield. The monks were indignant. Why should the vessels of gold on the abbot’s table be spared while the shrine of the saint was defaced? Abbot Ralph’s action was sacrilegious ; but he made compensation which was for the ultimate honour of St. Alban, for he appropriate the greater part of the rents of that manor to the perpetual keeping–up of the shrine. The next abbot,

Robert de Gorham,

solicited the Pope—Adrian IV, the Englishman—to take measures to compel

the monks

of Ely to forbear asserting that they were the possessors of the true

relics.

It was asserted that St. Alban sometimes issued from and returned to

his

shrine, thereby testifying that his relics were safe in his own church

and not

Ely. 2 --37-- a commission of

three bishops to

make a strict inquiry. They went to Ely

and on pain of excommunication the convent confessed “that they had

been

deceived by a pious fraud ; that they had perpetuated sacrilege, and

were

without one bone of St. Alban.” 3 This abbot once again restored the feretory,

as it was before Ralph’s vandalism, with much ornament of gold, silver,

and

precious stones. The succeeding abbot

employed

John, a goldsmith, to yet further embellish the shrine, and Matthew of

Paris,

that indefatigable historian and artist, says that the had never seen

one more splendid

and noble. To him we are indebted for a

drawing of it, which, together with his description, enables us to

realize the

beauty of the shrine of In those days

the high altar

screen had not been built, and the feretory could be seen by those in

the

choir, over the dorsal, as it stood on a stone substructure. The feretrum on

the two sides was overlaid with

figures of gold and silver, showing the acts of St. Alban in high

relief. At the eastern end was a large

crucifix with

the attendant figures of St. Mary and In this drawing the feretory has been taken down from the fixed shrine and placed on a bier, richly draped, or [sic] the poles have been passed through attached rings, and it is being carried in procession on the shoulders of four monks. --38-- This beautiful work was unfortunately done with borrowed money, and at the death of the abbot, among the creditors who pressed their claims was one Aaron, a Jew, who came to the abbey and boasted “that he had built that noble shrine ; and that all the grand entertainment of the place had been furnished out of his money.” While making some repairs at the east end of the church in 1256 the original coffin of St. Alban, which had long since been discarded, was found, and by its old

[Illustration:

The Feretory of associations with the saint had become endowed with miraculous properties, as was attested on that occasion. The following year the king came to the shrine and offered a curious and splendid bracelet, valuable rings, and a large silver cup, in order to deposit therein the dust and ashes of the venerable martyr ; he also gave some palls of silk to cover the old monument of the saint. On another occasion he had offered rich palls, bracelets, and gold rings, and gave the convent permission to convert them into money, provided they expended it in decorating --39-- the shrine. Among the permanent decorations of the feretrum were two suns of gold. Thomas de la Mare added many valuable ornaments to the shrine, and a large eagle of silver and gold which stood on the crest, the gift of Abbot Michael, he re-beautified. Among the benefactors to the shrine, Edward I gave a large image of silver gilt ; Edward III offered many rich jewels of gold and precious stones ; and Richard II presented a necklace for the image of the Blessed Virgin which was on the west end of the feretory. Other pilgrims offered various gifts : Adam Panlyn gave a sliver basin which was suspended over the shrine to receive alms ; Lord Thomas of Woodstock, a necklace of gold adorned with sapphire stones, with a pendant of a white swan expanding its wings, and two cloths of gold for a covering for the shrine ; Sir Robert de Walsam, precentor of Sarum, gave jewels ; another gave a sapphire “of admirable beauty” ; and another a richly ornamented zone. The abbot John Wheathampsted had the Life of St. Alban translated from Latin into English at a cost of three pounds (about £50), and deposited it on the shrine for the edification of the pilgrims. He also, at his own expense, had a picture of the saint painted and decorated with gold and silver, which he suspended over the shrine ; and it was said that the ornament exceeded the merit of the artist. It cost 50 marks, besides 795 ounces of plate used in embellishing it. Many names of the custodians of these treasures find mention in the numerous manuscripts written in the scriptorium of this abbey, one of whom—Robert Trynoth, feretrius—was buried in the retro-choir, beneath the shadow of these shrines he had so diligently tended. The fixed structure on which the feretory rested was --40-- taken down by Abbot John (1302 – 1308) and replaced by one of greater magnificence at a cost of 820 marks ; the remains are visible at the present day. No representation of this was left to us, and until quite recently the form of it was unknown. Desecration and

destruction (which

may be followed in detail with the shrines of St. Cuthbert and In 1847, the rector had certain walled-up arches and windows reopened, and among the débris were found many fragments of beautifully wrought Purbeck marble. These were carefully preserved, and when, in 1872, a great number of corresponding pieces were discovered, Mr. J. T. Micklethwaite, assisted by the foreman of the works, patiently fitted together over two thousand fragments of marble and clunch—a veritable work of love, which restored the better part of the substructure whereon the feretory had rested. It was a marvelous accomplishment, and it enables the present generation to picture the beauty it presented to the pilgrims who thronged around the shrine. This

structure, 8 feet 4 inches in height, is composed of a paneled base

decorated

with quatrefoils, upon which rise ten canopied niches, with backgrounds

of thin

plates of coloured clunch yet retaining much of their

colouring—vermilion and

blue-blazoned with the three lions of --41-- The third

portion of the

shrine—the protecting cover—is the only part of which we have no

representation. It was presumably of

wainscot similar to

those of

[Illustration:

Shrine of made on the same principle, to be lowered over the costly feretrum for protection and to be raised to exhibit it to the pilgrims, for in the roof immediately over the centre of the shrine is a hole through which a pulley was fixed : and --42--

[Illustration: --page not numbered-- --blank page-- if it is this canopy which is mentioned by Matthew of Paris as having the inside covered with crystal stones, what a spectacle it must have presented, as it slowly rose before the assembled pilgrims ! The lights from innumerable tapers would cause the crystals to scintillate with an indescribable magnificence. The watch-loft on the northside of the shrine is the most perfect left to us. It is a two-storied building of oak ; in the lower portion are aumbries [book cupboards], which contained various smaller relics, and which have shutters to ensure their safety. A narrow stairway of oaken beams ascends to the watching-chamber above, in which was posted a monk to see that no damage was done to the feretory when the protecting cover was raised and the jewelled reliquary exposed for the veneration of the pilgrims. At the demolition of shines there were among the ornaments brought to the treasure-house of Henry VIII “great agates, cameos, and coarse pearles set in gold, from St. Albans,” some of which were probably the antique gems which had been gleaned from the ruins of the Roman city of Verulam by the early abbots of St. Albans. A few shrines

have in latter days

been partially restored, but in no other case has there been so

complete and

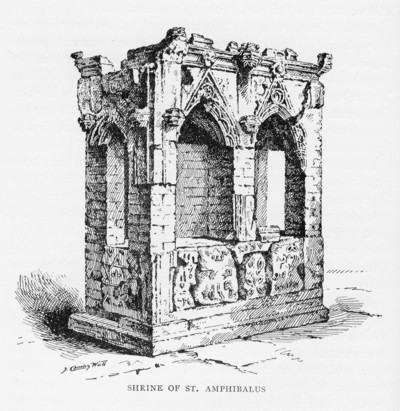

wonderful a restoration as we have a Within the same old abbey another shrine has been re-erected—the shrine of St. Alban’s teacher, the priest who had been instrumental in bringing St. Alban into the Church ; the priest who, by St. Alban’s exchange of cloaks, had been enabled to escape his persecutors for a time, allowing the latest convert to be the first to witness by his blood the faith of Christ. Whether St. Amphibalus be the name of the man, or a name conferred through the --43-- incident of the cloak, matters not ; by that name is the martyr revered, and by that name has he been known for generations in the Church’s calendar. St. Amphibalus

was apprehended

very shortly after the martyrdom of St. Alban. He

was brought with certain of his converts to the Hitherto the shrine of St. Amphibalus had been in close proximity to that of St. Alban, but when William de Trumpington became abbot he prepared another position for it, where St. Amphibalus should be venerated by himself and not receive a mere share of the divided attention of the pilgrims with the proto-martyr. This was in the middle of the ante-chapel of the Lady Chapel, or the retro-choir, where a high fixed shrine was decorated by Walter de Colchester, the sacrist, who was an excellent painter and an “incomparable carver.” It was enclosed with an iron grating, “where had been fixed a decent altar with a painting and other suitable ornaments” ; and the whole was consecrated by the Irish bishop of Ardfert. The two gilt shrines in which the relics of St. Amphibalus and his companions had first been deposited were given to the --44-- newly built church at Redbourn to honour that place with mementoes of its own martyrs, and the abbot appointed that a perpetual guard should be kept over them both day and night by a relay of monks. The shrine of St. Amphibalus was rebuilt, during the time of Abbot Thomas de la Mare, at the cost of the sacrist, Ralph Witechurche, and the eastern end was adorned by the abbot with images and silver-gilt plates at a cost of £8 8s. 10d. (about £168 16s. 8d.). At the time when the fragments of St. Alban’s shrine were found (1872), many pieces of finely carved white stone, or clunch, were also discovered, which proved to be parts of the pedestal of the shrine of St. Amphibalus. These have been fitted together, and although in a very fragmentary and imperfect state, sufficient has been restored to enable a fairly correct conclusion as to its former appearance. Standing on a step of 6 inches in height is a basement 23 inches high, 6 feet long, and nearly 4 feet wide. This is covered with a curiously sculptured fretwork, the western end bearing the remains of the saint’s name, A M P H I B . . . S and a fleur-de-lys. On the north and south sides are the initials R. W. of Ralph Witechurche and fleur-de-lys ; but the eastern end, which was decorated with silver-gilt figures, is naturally lost. Above the basement, on either side, is an open arcade of two bays, and at each end is a single arch, all of which are canopied and have straight-sided crocketed pediments. Originally there were three shafts at each side and two at the ends, of which only the capitals remain ; they are elaborately sculptured with a goat and masks, and some of them retain traces of colour and gilding. Surmounting the whole is a cornice 12 inches high, making the total height from the pavement 7 feet 7 inches. --45-- Another relic of St.

Amphibalus—a

hand, or fragment of that member—was enshrined in a hand reliquary,

richly

decorated with silver and precious stones, and presented by William

Westwyck,

who for so great a benefaction was awarded a final resting-place near

the

shrine of that saint in the retro-choir close by the altar of the “four

wax

candles.”

[Illustration:

Shrine of St. Amphibalus] --46-- --blank page-- Footnotes~ -end of chapter- |

| Historyfish pages,

content, and design copyright (c) Richenda

Fairhurst, 2008 All rights reserved. No commercial permissions are granted. The Historyfish site, as a particular and so unique "expression," is copyright. However, some (most) source material is part of the public domain, and so free of copyright restrictions. Where those sections are not clearly marked, please contact me so I can assist in identifying and separating that material from the Historyfish site as a whole. When using material from this site, please keep author, source, and copyright permissions with this article. Historyfish intends to generate discussion through shared information and does not claim to provide, in any way, formal, legal, or factual advice or information. These pages are opinion only. Opinions shared on historyfish are not necessarily the opinions of historyfish editors, staff, owners or administrators. Always consult proper authorities with questions pertaining to copyrights, property rights, and intellectual property rights. It is my intent to follow copyright law (however impossibly convoluted that may be). Please contact me should any material included here be copyright protected and posted in error. I will remove it from the site. Thank you. |