CHAPTER

XI

THE

VARIOUS RELIGIOUS

ORDERS

The various

Orders existing in England

in pre-Reformation days may be classified under four headings (1)

Monks, (2)

Canons Regular, (3) Military Orders, and (4) Friars. As

regards the nuns, most of the houses were

affiliated to one or other of the above-named Orders.

I.

Monks

i. Benedictines

St. Benedict,

justly called the

Patriarch of Western Monachism, established his rule of life in Italy

; first at Subiaco and subsequently at Monte Cassino about A.D. 529. The design of his code

was,

like every other rule of regular life, to enable men to reach the

higher

Christian ideals by the helps afforded them in a well-regulated

monastery. According to the saint's original conception, the

houses were

to be separate families independent of each other. It was no part

of his

scheme o establish a corporation with branches in various localities

and

countries, or to found an "Order" in its modern sense. By its

own inherent excellence and because of the sound common-sense which

pervades

it, the Rule of St. Benedict at once began to take root in the

monasteries of

the West,

--- 213---

till it quickly

superseded any

others then in existence. Owing to its broad and elastic character, and

hardly

less, probably, to the fact that adopting it did not imply the joining

of any

stereotyped form of Order, monasteries could, and in fact did, embrace

this

code without entirely breaking with their past traditions. This,

side by

side in the same religious house, we find that the rule of St. Columba

was

observed with that of St. Benedict until the greater practical sense of

the

latter code superseded the more rigid legislation of the

former.

Within a comparatively short time from the death of St. Benedict in A.D. 543, the Benedictine became the

recognised

form of Western regular life. To this end the action of Pope St.

Gregory

the Great and his high approval of St. Benedict's Rule greatly

conduced.

In his opinion it manifested no common wisdom in its provisions, which

were

dictated by a marvellous insight into human nature and by a knowledge

of the

best possible conditions for attaining the end of all monastic life,

the

perfect love of God and of man. Whilst not in any way lax in its

provisions,

it did not prescribe an asceticism which could be practiced only by the

few ;

whist the most ample powers were given to the superior to adapt the

regulation

to all circumstance of time and places ; thus making it applicable to

every

form of the higher Christian life, from the secluded cloister to that

for which

St. Gregory specially used those trained under it : the evangelisation

of

far-distant countries.

The

connection between the Benedictines and England

began with the mission of St. Augustine

in A.D. 597. The Monastery

of Monte

Cassino having been destroyed by the Lombards,

toward

the end of the sixth century,

---214---

--215---

---216---

<>the monks took

refuge in Rome,

and were placed in the Lateran, and by St. Gregory in the church he

founded the

honour of St. Andrew, in his ancestral home on the Coelian Hill.

It was

the prior of St. Andrew's whom he sent to convert England.

With the advent of the Scottish monks from Iona

the

system of St. Columba was for a time introduced into the North of

England ; but

here, as in the rest of Europe, it quickly gave

place to

the Benedictine code ; and practically during the whole Saxon period

this was

the only form of monastic life in England.

ii. Cluniacs

The Cluniac

adaptation of the

Benedictine Rule took its rise in A.D. 912 with Berno, abbot of Gigny. With the assistance of the Duke of Aquitaine

he built and endowed a monastery at Cluny,

near Macon-sur-Saone. The Cluniac was a

new departure in monastic government. Hitherto the monastery was

practically

self-centered ; any connection with other religious houses was at most

voluntary, and any bond of union that may have existed, was of the most

loose

description. The ideals upon which Cluny

was established was the existence of a great central monastery with

dependencies spread over many lands, and forming a vast feudal

hierarchy of

subordinate establishments with the closest dependence on the

mother-house. Moreover, the superior of

each of the dependent monasteries, no matter how large and important,

was not

the elect of the community, but the nominee of the abbot of Cluny ; and in the same way the profession of every

member of the congregation was made in his home and with his sanction. It was a great ideals ; and

for two

---217---

centuries the

abbots of Cluny

form a dynasty worthy of so lofty a position. The

first Cluniac house founded in England

was that of Barnstable. This was speedily followed by that of Lewes,

a priory set up by William, earl of Warren,

in A.D. 1077, eleven years only after the Conquest.

The last was that of Stonesgate, in Essex,

made almost exactly a century later. On

account of their dependence upon the abbot of Cluny,

several of the lesser house were suppressed as “alien priories” towards

the

close of the fourteenth century, and those that remained gradually

freed

themselves from their obedience to the foreign superior.

At the time of the general suppression in the

sixteenth century there were thirty-two Cluniac houses ‘ one only,

Bermondsey,

was an abbey ; the rest were priories, of which the most important was

that

which had been nearly the first in order of time, Lewes.

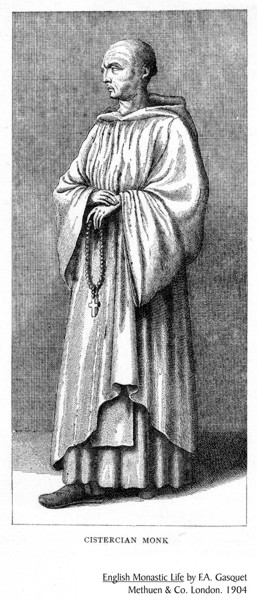

iii.

Cistercians

The

congregation of Citeaux was

at one time the most flourishing of the offshoots of the great

Benedictine

body. The monastery of Citeaux was

established by St. Robert of Molesme in A.D. 1092.

The saint was a Benedictine, and felt himself

called to something different to what he had found in the monasteries

of France. The peculiar system of the Cistercians,

however, was the work of St. Stephen Harding, an Englishman, who at an

early

age had left his own country and never returned thither.

He struck out a new line, which was a still

further departure from the ideal of St. Benedict that was the Cluniac

system. The Cistercians, whilst strictly

maintaining the notion that each monastery was a family endowed with

the

principles of fecundity, formed themselves into an Order,

---218---

---219---

---220---

in the sense of

an organized

corporation, under the perpetual pre-eminence of the abbot and house of

Citeaux, and with yearly Chapters at which all superiors were bound to

attend. It was the chief object of the

administration to secure absolute uniformity in all things and

everywhere. This was obtained by the

Chapters, and by

their visitations of the abbot of Citeaux, made anywhere and everywhere

at

will. The Order spread during the first

century of its existence with great rapidity. It

is said that , by the middle of the twelfth century,

Citeaux had five

hundred dependencies, and that fifty years later there were more than

three

times that number. In England

the first abbey was founded by King Henry I, at Furness in A.D. 1127

and of the

hundred houses existing at the general suppression three-fourths had

been

founded in the twelfth century. The

rest, with the exception of St. Mary Grace, London,

established in 1349 by Edward III., were founded in the early part of

the

thirteenth century.

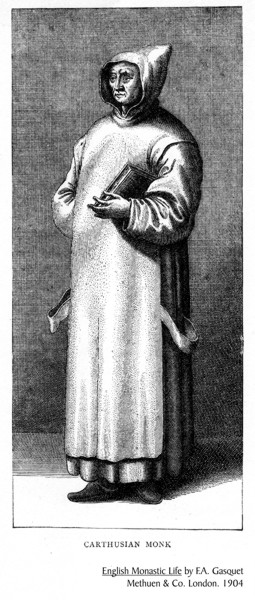

iv. Carthusians

The Carthusians were founded in the eleventh

century by St.

Bruno. With the help of the bishop of Grenoble

he built for himself and six companions, in the mountains near the

city, an

oratory and small separate cells in imitation of the ancient Lauras of

Egypt. This was in A.D. 1086 ; and the

Order takes its designation from the name of the place--Chartreuse. Peter the Venerable, the celebrated abbot of Cluny,

writing forty years after the foundation, thus describes their austere

form of

life. “Their dress,” he says, “is meaner

and poorer than that of other monks, so short and scanty and so rough

that the

very sight affrights one. They wear coarse

hair-shirts

---221---

next to their

skin ; fast almost

perpetually ; eat only bean-bread ; whether sick or well never touch

flesh ;

never buy fish, but eat it if given them as an alms ;

eat eggs on Sundays and Thursdays ; on

Tuesday and Saturdays their fare is pulse or herbs boiled ; on Mondays,

Wednesdays, and Fridays they take nothing but bread and water ; and

they have

only two meals a day, except within the octaves of Christmas, Easter,

Whitsuntide, Epiphany, and other festivals. Their

constant occupation is praying, reading and manual

labour, which

consists chiefly in transcribing books, They

say the lesser Hours of the Divine Office in their

cells at the

time when the bell rings, but meet together at Vespers and Matins with

wonderful recollection”

A

manner of life of such great austerity naturally did not attract many

votaries. It was a special vocation to

the few, and it was not until A.D. 1222 that the first house of the

Order was

established in England,

at Hinton, in Somersetshire, but William Langesper.

The last foundation was the celebrated

Charterhouse of Shene, in Surrey, made by King

Henry

V. At the time of the general

dissolution, there were in all eight English monasteries and about a

hundred

members.

II. The Canons Regular

The clergy of

every large church were in ancient times called canonici—canons—as

being on the list of those who were devoted to

the service of the Church. In the eighth

century, Chrodegand, bishop of Metz,

formed the clergy of his cathedral into a body, living in common under

a rule

and bound to the public recitation of the Divine

---222---

---223---

---224---

Office. They were known still as canons, or those

living under a rule of life like the monks, from the true meaning of

κανών, a

rule. The common life was in time

abandoned in spite of the provisions of several Councils, and then

institutions

other than Cathedral Chapters became organised upon lines similar to

those laid

down by Chrodegand, and they became known as Canons Regular. They formed themselves generally on the

so-called Rule of St. Augustine, and became known, in England

at least, as Augustinian Canons, Premonstratensian Canons, and

Gilbertine

Canons.

i. Augustinian Canons

The early

history of the Austin, or Black Canons, is involved in considerable

obscurity,

and it is only after the beginning of the twelfth century that these

Regulars

are to be found in Europe.

The Order was conventual, or monastic, rather

than congregational or provincial, like the Friars : that is, the

members were

professed for a special house and belonged by virtue of their vows to

it, and

not to the general body of their brethren in the country.

In one point they were not so closely bound

to their house as were the monks. The

Regular Canons were allowed in individual cases to serve the parishes

that were

impropriated to their houses ; the monks were always obliged to employ

secular

vicars in these cures. The Augustinians

were very popular in England

; most of their houses having been established in the thirteenth and

fourteenth

centuries. The earliest foundation was

that of Christ Church,

or Holy Trinity, Aldgate, made by Queen Maud in A.D. 1108 ; and at the

time of

the dissolution there were about 170 houses of Augustinian Canons

---225---

in England

; two of the abbeys, Waltham Cross and Cirencester, being governed by

mitered

abbots. In Ireland

they were even more popular and numerous, the number of the houses of

canons

being put at 223, together with 33 nunneries. The

Augustinian priors of Christ

Church, and All

Hallows, Dublin,

and seen other priors of the Order, had seats in the Irish Parliament. The habit of the Order was black, and hence

they were frequently known as Black Canons.

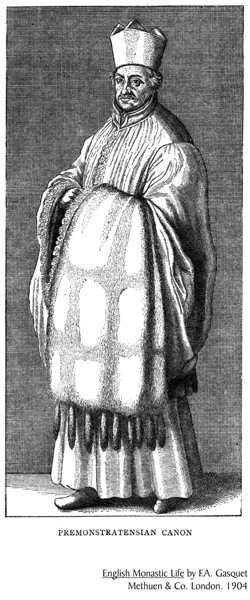

ii. The Premonstratensian Canons

This branch of

the Canons Regular was established by St. Norbert in A.D. 1119 at a

place

called Prémontré, a lonely and desolate valley near Laon

in France. Their founder gave them the Rule of St.

Augustine, and they became known either as Premonstratensians, from

their first

foundation, or Norbertines, from their founder. The

habit of these canons was white, with a white rochet

and even a

white cap, and for this reason they were frequently known as White

Canons. Besides following the ordinary

Augustinian

Rule, these Canons made Prémontré into a “mother-house,”

and the abbot of

Prémontré was abbot-general of the entire Order : having

the right to visit,

either by himself of deputy, every house of the congregation ; to

summon every

superior to the yearly General Chapter ; and to impose a tax for the

use of the

Order upon all the houses. This, so far

as England

is

concerned, lasted in theory until A.D. 1512, when all the English

houses were

placed under the abbot of Welbeck. Previously

they had been for more than thirty years supervised on behalf of the

abbot of

Prémontré, by Bishop Redman, who also continued to hold

the office of abbot

---226---

---227---

---228---

of Shap. In England,

just before the dissolution, there were some thirty-four houses of the

Order.

iii. The Gilbertines

The Canons of

St. Gilbert of Sempringham are said to have been established in A.D.

1139,

although the actual foundation as early as A.D. 1131, others as late as

A.D.

1148. St. Gilbert, the founder, was

Rector of Sempringham and composed his rule from those of St. Austin

and St.

Benedict. It was a dual Order, for both

men and women ; the former followed ST. Augustine’s

code with some additions, whilst the women took the Cistercian

recension of the

Benedictine Rule.

These canons,

according to Dugdale, had a black habit with a white cloak and a hood

lined

with lamb’s wool. The women were in

black with a white cap. In the double

monasteries the canons and nuns lived in separate houses having no

communication. AT first the Order

flourished greatly. St. Gilbert in his

lifetime founded thirteen houses, nine for men and women and four for

men

only. In these there are said to have

been seven hundred canons and fifteen hundred sisters.

The order was

under the rule of a general superior, called the master or

prior-general. His leave was necessary for

the admission of

members, and in fact, to initiate business or at least give validity to

the

proposals of any house. There were, in

all, some twenty-six of these establishments in England

at the time of the general dissolution. Four

only of these were considered as ranking

among the greater monasteries whose income was above £200 a year.

---229---

The

Military Orders

i. Knights Hospitallers of St. John of Jerusalem

The Hospitallers

began in A.D. 1092 with the building of a hospital for pilgrims at Jerusalem. The original idea of the work of these

visiting knights was to provide for the needs of pilgrims visiting the Holy

Land and to afford them protection on their way. They, too,

followed a rule of life founded upon that of St.

Augustine,

and their dress was black with a white cross upon it.

They came to England

very shortly after their foundation, and had a house built for them in London

in A.D. 1100. They rose in wealth and

importance in the country ; and their head, or grand prior as he was

called,

became the first lay baron in England,

and had a seat in the House of Peers.

Upon many of

their manors and estates the Knights Hospitallers had small

establishments name commanderies, which were under the

government of one of their number, called the commander.

These houses were sometimes known as preceptories,

but this was a term more

generally used for the establishments of the other great Military

Order, known

as the Templars. An offshoot of both

these orders was known as “The Order of St. Lazarus of Jerusalem.” There were a few houses of this branch in England,

which was founded chiefly to assist and support lepers and indigent

members of

the Military Orders. They are, however,

usually regarded as hospitals. The Knights

of St. John of Jerusalem had their headquarters at the Hospital

of St. John, near

Clerkenwell, to

which were attached some fifty-three cells or commanderies.

---230---

---231---

---232---

ii. The

Templars

The Military

Order of the Templars was founded, according to Tanner, about the year

A.D.

1118. They derived their name from the Temple

of Jerusalem, and the

original

purpose of their institute was to secure the roads to Palestine,

and protect the holy places. They must

have come into England

early in the reign of King Stephen, as they had several foundations at

this

time, the first being that in London

which gave its name to the present Temple. They became too right and powerful ; and

having been accused of great crimes, their Order was suppressed by Pope

Clement

V in 1309 : an act which was confirmed in the Council of Vienne in 1312. The head of the Order in England

was styled the “Master of the Temple,”

and was sometimes, as such, summoned to Parliament.

Upon

there manors and estates the Templars, like the Hospitallers,

frequently built

churches and houses, in which some of the brethren lived.

These were subordinate to the London

house and were in reality cells, under the title of “Preceptories.” On the final suppression of the Order, their

lands and houses, to the number of eighteen, were handed over to the

Knights of

St. John of Jerusalem. One house,

Ferriby, in Yorkshire, became a priory of

Austin Canons,

and four other estates appear to have been confiscated.

In all there were some three-and-twenty

preceptories connected with the London

Temple.

---233---

IV. The Friars

The friars

differed from the monks in certain ways. The

brethren by their profession were bound, not to any

locality or

house, but to the province, which usually consisted of the entire

number of

houses in a country. They did not,

consequently,

form individual families in their various establishments, like the

monks in

their monasteries. They also, at first,

professed the strictest poverty, not being allowed to possess even

corporate

property like the monastic Orders. They

were by their profession mendicants, living on alms, and only holding

the mere

buildings in whey they dwelt. 234

i. The Dominicans, or Black

Friars

The founder of

these friars was a Spaniard named Dominic, a canon of the diocese of

Osma, in Old Castile, at the close of the

twelfth century. They were known as

Dominicans, from their

founder ; “Preaching Friars,” from their mission to convert heretics ; in England, “Black Friars,” from the colour

of their cloak ; and in France, “Jacobins,” from having had their first

house

in the Rue St. Jacques, at Paris. Their

rule was founded on that of St. Augustine,

and it was verbally approved in the Council of Lateran in A.D. 1215,

and the

following year formally by Honorius III. Their

founder, having been a secular canon of Osma in Spain,

his friars t first adopted the ordinary dress of canons ; but about

A.D. 1219

they took a white tunic, scapular, and hood, over which, when in church

of when

they went abroad, they wore a black cappa,

or cloak, with a hood of the same color. They

first came to England

with Peter de Rupibus, bishop

---234---

---235---

---236---

of Winchester,

in A.D. 1221 and their Order quickly spread. In

the first year of their arrival they obtained a

foothold in the University

of Oxford, and at the time

of the

general suppression of the religious Orders in the Sixteeth century

they had

fifty-eight convents in the country.

ii The Franciscan, or Grey

Friars

St. Francis the

founder of the Grey Friars was contemporary with St. Dominic, and was

born at Assisi,

in the province of Umbria

in Italy,

in

A.D. 1182. These friars were called

Franciscans from their founder ; “Grey Friars” from the colour of their

habit ;

and “Minorites” from their humble desire to be considered the least of

the

Orders. Their rule was approved by

Innocent III in A.D. 1210 and by the General Council of the Lateran in

A.D.

1215. Their dress was made of a course

brown cloth with a long pointed hood of the same material, and a short

cloak.

They girded themselves with a knotted cord and went barefooted. The Franciscan Friars first found their way

to England

in

A.D. 1224, and at the general destruction of Regular life in England

in the sixteenth century they had in all about sixty-six establishments. A reformation of the Order to primitive

observance was made in the fifteenth century and confirmed by the

Council of

Constance in A.D. 1414. The branches of

the Order with adopted it became known as “Observants” or “Recollects.”

This

brand of the Order was represented in England

by several houses built for them by King Henry VII although they are

supposed

to have been brought into England

in the time of Edward IV.

The whole Order

in England

was divided into seven “Custodies” or “Wardenships,” : the houses being

---237---

grouped round

convenient centres

such as London, York,

Cambridge, Bristol,

Oxford, Newcastle,

and Worchester. Harpsfield says that the

“Recollects” or “Observants” had six friaries, at Canterbury,

Greenwich, Richmond,

Southampton, Newark,

and Newcastle.

The Minoresses, or Nuns of St. Clare

The Minoresses

were instituted by St. Clare, the sister of St. Francis of Assisi,

about A.D. 1212, as the branch of the Franciscan Order for females. The followed the Rule of the Friars Minor and

were thus called “Minoresses,” or Nuns of St. Clare, after their

foundress. They wore the same dress as

the Franciscan Friars, and imitated them in their poverty, fro which

cause they

were sometimes known as “Poor Clares.” They

were brought to England

somewhere about A.D. 1293, and established in London,

without Aldgate, in the locality now known as the Minories. The Order had two other houses, one at

Denney, in Cambridgeshire, in which at the time of the general

dissolution

there were some twenty-five nuns ; and

the other at Brusyard in Suffolk,

which was a much smaller establishment. The

nuns at Denney had previously been located at

Waterbeche for about

fifty years, being removed to their new home by Mary, countess of

Pembroke, in

A.D. 1348.

iii. Carmelites

The Carmelite

Friars were so called from the place of their origin.

They were also named “White Friars” from the

colour of the cloak of their habit, and Friars of the Blessed Virgin. These friars are first heard of in the

twelfth century, on being driven out of Palestine

by the persecution of the Saracens. Their

Rule is chiefly founded

---238---

---239---

---240---

on that of St.

Basil, and was

confirmed by Pope Honorius III, in A.D. 1224, and finally approved by

Innocent

VI, in 1250. They were brought into England

by John Vesey and Richard Grey, and established their first houses in

the north

at Alnwick, and in the south at Ailesford in Kent. At the latter place the first European

Chapter of the Order was held in A.D. 1245. In

the sixteenth century there were about forty houses in England

and Wales.

iv. Austin Friars, or Hermits

The body of

Austin Friars took

its historical origin in the union of several existing bodies of friars

effected in A.D. 1265 by Pope Clement IV. They

were regarded as belonging to the ranks of the

mendicant friars and

not to the Monastic Order. They were

very widely spread, and in Europe in the

sixteenth

century they are said to have possessed three thousand convents, in

which were

thirty thousand friars ; besides three hundred convents of nuns. In England

at the time of the dissolution they had some thirty-two friaries. 241

V.

The Lesser Friars

i. Friars of the Sack, or De

Penitentia

These brethren

of penance were

called “Friars of the Sack” because there dress was cut without other

form than

that of a simple bag or sack, and made of coarse clothe, like sackcloth. Most authorities, however, represent this as

merely a familiar name, and say that their real title was that of

Friars, or

Brethren of Penance. They took their origin apparently in Italy,

and came to England

during the reign of Henry III., where, about A.D. 1257, they

---241---

opened a house

in London.

They had many settlements in France,

Spain,

and Germany,

but lost most of them after the Council of Lyons in A.D. 1274, when

Pope

Gregory X. suppressed all begging friars with the exception of the four

mendicant Orders of Dominicans, Franciscans, Austin Friars, and

Carmelites. This did not, however, apply

universally, and

in England,

the Fratres de Sacco remained in

existence until the final suppression of the religious Orders in the

sixteenth

century. The dress of these friars was

apparently made of rough brown cloth, and was not unlike that of the

Franciscans ; they had their feet bare and world wooden sandals. Their mode of life was very austere, and they

never ate meat and drank only water.

ii. Pied Friars, or Fratres de

Pica

These religious were so called from the

colours of their habit, which was black and white, like a magpie. They had but one house in England,

at Norwich, and had only a

brief

existence, as the Pied Friars were obliged, by the Council of Lyons, to

join

one or other of the four great mendicant Orders. Their house, which,

according

to Blomfield, stood in the north-east corner of the churchyard of St.

Peter’s

Church, was given to the hospital

of Bek,

at Billingford in Norfolk.

iii. Friars of St. Mary de Areno

There friars had likewise but one house,

at Westminster, founded

towards the

end of the reign of Henry III. They,

too, were short-lived as a body, falling under the law of suppression

of the

lesser mendicant Orders. They, however,

continued

for a few years longer, as Tanner quotes a

---242---

<> <>

---243---

---245---

Close Roll of I I Edward

II., to show that they were only dissolved in that

year, A.D.

1318.

vi. Friars of Our Lady, or de

Domina

The

friars of Our Lady are said to have lived under the Rule of St. Austin. They had a white habit, with a black cloak

and hood. They were instituted in the

thirteenth

century, and had a house at Cambridge,

near the castle. Before A.D. 1290 they

were also settled at Norwich,

where

they continued until the great Pestilence in 1349, of which they all

died.

v. Friars of the holy Trinity,

or Trinitarians

These

religious were founded by SS. John of Matha and Felix of Valois about

A.D. 1197

for the redemption of captives. They

were called “Trinitarians,” because

by their rule all their churches were dedicated to the Holy Trinity, or

“Maturines,” from the fact that their

original foundation in Paris

was

near St. Mathurine’s Chapel. The Order

was confirmed by Pope Innocent III., who gave the religious white

robes, with a

red and blue cross on their breasts, and a cloak with the same emblem

on the

left side. Their revenues were to be

divided into three parts ; one for their own support, one to relieve

the poor,

and the third to ransom Christians who had been taken captive by the

infidels. They were brought to England

in A.D. 1244, and were given the lands and privileges of the Canons of

the Holy

Sepulchre on the extinction of that order. According

to the Monasticon,

they had, in all, eleven houses in this country ; but these

establishments were

small, the usual number of religious in each being three friars and

three lay

brothers. The superior was

---245---

named

‘”minister,” and included

in his office the functions of superior and procurator ; and the houses

were

united into a congregation under a Minister

major, who held a general Chapter annually for the regulation of

defects

and the discussion of common interests.

vi. Crutched, of Crossed Friars

The

Crossed Friars are said by some to have taken their origin in the Low

Countries, by others to have come from Italy in very early times,

having been

instituted or reformed by one Gerard, prior of St. Maria di Morella at

Bologna. In 1169 Pope Alexander III.

took them under his protection and gave them a fixed rule of life. These friars first came to England

in the year 1244. Matthew Paris, writing

of that time, says that they appeared before a synod held by the bishop

of Rochester,

each carrying a stick upon which was a cross. They

presented documents from the pope and asked to be

allowed to make

foundations of their fraternity in England. Clement Reyner put their first establishment

in this country at Reigate, in 1245, and their

second in London in 1249. This last is the better known, as it has

given the name of Crutched Friars to a locality in the city of London. The friars had a third house at Oxford,

and altogether there were six or seven English friaries.

Besides the cross upon their staves, from

which they originally took their name, the friars had a red cloth cross

upon

the breasts of their habits.

vii.

The Bethelmite Friars

The

origin of these friars is uncertain, and they were apparently only

known in England,

and so may perhaps

---264---

---265---

---266---

be considered

to have had their

beginning in this country. Matthew Paris

says that in the year 1257 they were given a house at Cambridge,

in Trumpington Street.

He

describes their dress as being very like that of the Dominicans, from

which it

was distinguished only by having a red star, or five points with a

round blue

centre, on the scapular. This badge

recalled the meaning of their name, representing as it did the star

which led

the Magi to Bethlehem.

viii. The Bonshommes

These friars

were apparently of

English Origin. Some have thought that

they were the same as the “Friars of the Sack,” but this is by no means

clear. Polydore Vergil says that Edmund

of Cornwall, the brother of Henry III., on his return from Germany

in A.D. 1257, built and endowed a fine monastery at Ashridge. This he gave “to a new order of men, never

before known in England,

called Boni Homines, the Bonshommes.

They followed the rule of St.

Augustine, wearing a blue-coloured dress of a

form

similar to that of the Augustinian Hermits.” The

only other house possessed by the Bonshommes was at

Edingdon.

---249---

--end

chapter--

|

<>

<>