|

|

Public Domain text

transcribed

and prepared "as is" for HTML and PDF

by Richenda Fairhurst, historyfish.net. July 2007. No commercial permissions granted. Text may contain errors. (Report errors to  ) ) |

|

THE OBEDIENTIARIES

The officials of a monastery

were frequently known by the name of obedientiaries.

Sometimes under this name were included even

the prior and sub-prior, as they also were appointed by the abbot, and

were, of course, equally with the others in subjection and obedience to

him. But as usually understood, by the word obedientiaries was

signified the other officials, and not the prior and

sub-prior, who assisted in the general government of the monastery.

Various duties were assigned to all

obedientiaries, and they possessed extensive powers in their own

spheres. Very frequently in medieval times they had the

full management of the property assigned to the special support of the

burdens of their offices. Their number naturally varied considerably in

different monasteries ; but here it may be well

to describe briefly the duties of each of the ordinary officials, as

they

are set forth in the monastic Custumals that have com down to us.

The cantor was one of the most

important officials in the monastery. He was appointed, of course, by

the abbot, but with a necessary regard to the varied qualifications

required for the

office ; for the cantor was both

---58--- singer, chief librarian, and

archivist. He should be a priest, says

one English Custumal, of proved, upright character, wise and well

instructed in a knowledge pertaining to his office, as well as

thoroughly conversant

with ecclesiastical customs. Under his management all the church

services were arranged and performed : the

names of those who were to take part in the singing of Lessons or

Responsories

at Matins or other parts of the daily Office were set down by him on

the table,

or official programme, and no one could refuse any duty assigned to him

in

this way. In everything regarding the church services the cantor had no

superior except the abbot, although in

certain cases, where the Divine Office, for example, had been delayed

for some

reason or other , the sacrist might sign to him in suggestion that he

should

cause the singers to chant more briskly. What he

arranged to be sung had to be sung, what he settled to be read in the

refectory

had to be read ; the portion of Sacred Scripture, or other book that he

had marked for the evening Collation, had to be used, and no other.

The place of the cantor in the church was always on the right hand of the choir ; that of his assistant, the succentor, or sub-cantor, was on the left. It was part of the cantor's duty to move about the choir when it was necessary to regulate the singing, and especially when any Prose, or long Magnificat with difficult music was being sung. Above all things, he had to guard against mistakes, or even the possibility of mistakes, in the divine service by every means in his power. With this end in view, he was instructed to select only music that was known to all, and to see that it was sung in the traditional manner. To guard against faults in reading and singing ---59--- he was obliged by his office to

go over the Lessons for Matins with the younger monks, and to hear the

reader in the refectory before the meals, in order to point out defects

of pronunciation and quality, as well as to regulate the tone of the

voice and rate of reading.

---60--- When the abbot had to give out an Antiphon or Responsory on one of the greater feasts, the cantor always attended him, and helped him in there were need. If the abbot was unable to take any of this duties in church in the way of singing, such as celebrating the High Mass or intoning the Antiphons at the Benedictus and Magnificat, the cantor took them as part of the duties of his office. On all greater feasts of the second class, the cantor, by virtue of his office, gave out the Antiphon at the Benedictus and at the Magnificat. At the Mass and other solemn parts of the Divine Office on these occasions, he directed the choir with his staff of office : assisted on first-class days by six of the brethren in copes, and on feasts of the second class by four. His side of the choir was always to take up any psalm he had intoned ; the other side of the choir, under the direction of the sub-cantor, doing the same in regard to what he intoned. Even when the cantor himself was not directing the choir, as on ordinary days, he had to be always ready to come to the assistance of the community, in the case of any breakdown in the singing or hesitation as to the correct Antiphons to be used, etc. If an Antiphon was not given out or given out wrongly, or if the brethren got astray in the music, he was to set it right with as little delay as possible. If the tone of the chanting had to be raised or to be lowered, it was to be done only by him, and all had to follow his lead without hesitation. On festivals it was his duty to

select the singers of the Epistle and Gospel, and he was to be ever

guided in his choice of deacon and sub-deacon by his knowledge of their

capacity

to do honor to the feast by their good singing. When the community were

walking in procession through the

cloister or elsewhere, it was his duty to walk up and down, between the

ranks of

the brethren, to see that their singing was correctly rendered, and

that it

was kept together. The brethren were charged unhesitatingly to follow

his suggestion and his leading.

Besides this, the cantor was naturally to the instructor of music in the community, and at certain times he took the novices and trained them in the proper mode of ecclesiastical chanting and in the traditional music of the house. In many monasteries he had also to teach the boys of the cloister-school to read, and the exasperating nature of this part of his office may be perhaps gauged from a provision inserted in some statues, that he was on no account to slap their heads or pull their hair, this privilege being permitted only to their special master. On account of the cantor's care of the church services and necessary labour entailed thereby upon him, some indulgence was generally accorded to him in regard to his attendance at the parts of the Divine Office where his presence was not specially required. He was, however, forbidden to absent himself from two consecutive canonical hours, and was not to stay away from Matins, Vespers, or Compline. On Saturdays, like the rest, ha had to wash his feet in the cloister. So much with regard to the

duties of the precentor, as chief singer of the monastery. He was also

the librarian, or armarius ; the two offices, somewhat

strangely, perhaps,

---61--- to our modern notion, always

going together. In this capacity he had

charge of all the books contained in the aumbry, or book-cupboard, or

later in the book-room, or library. Moreover he had to prepare the ink

for the various writers of manuscripts and charters, etc.,

and to procure the necessary parchment for book-making. He had to watch

that the books did not suffer

from ill use, or misuse, and to see to the mending and binding of them

all. As keeper of the bookshelves, the

cantor was supposed to know the position and titles of the columns, and

by

constant attention to protect them from dust, and injury from insects,

damp, or

decay. When they required repair or cleaning, he was to see to it ; and

also to judge when the binding what

to be repaired or renewed, For the purpose of

this renovating the manuscripts under his care, he had, of course

frequently to employ skilled labour. At such times he

received an allowance of food for the workmen engaged on

"cleaning the bindings of the choir books," etc. Special revenues

also were at his disposal "for making new books and keeping up

the organs."

At the beginning of Lent the cantor was to remind the community in Chapter of those who had given the books to their house, or had written them ; and subsequently it was his duty to request that an Office and Mass for the Dead should be said for such benefactors. And, during the morning Mass of the first Sunday of Lent, he was to bring a collection of volumes into the Chapter-house, that the abbot might distribute one volume to each monk as his special Lenten reading. In the ordinary course, the precentor was bound to give out whatever books were required or asked for, taking care always to enter their ---62--- titles and the names of the

borrowers in his register. He was

permitted sometimes to lend the less precious manuscripts ; but if the

loan was made to someone outside the monastery, he had to see that he

received a

sufficient pledge for its safe return.

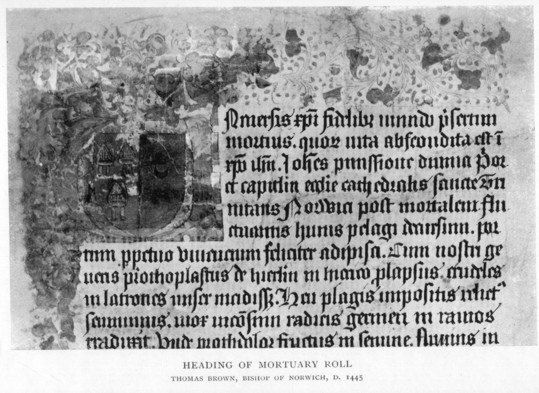

---63--- All writings of the church, or made for the church, came under the charge of the precentor. He made, for example, the tabulae, or lists of those taking any part in the services. These were graven on waxen tablets, the writing of which could easily be changed, and for makingand repairing of which the sacrist had to furnish the wax. Moreover, the precentor had to supply the writers with the parchment, ink, etc., for their work, and personally to hire the scribes and rubricators who labored for money. Also he was supposed to provide those in the cloister who could write and desired to do so, with whatever materials they required ; but before receiving these the religious had first to obtain leave from the abbot or superior, and then only to signify their wants to the precentor. He was told to give them what they needed, remembering that none of the brethren wrote or copied for their own personal good, but for the general utility of the monastery. The precentor also, in his capacity of librarian, had to provide the books used for reading and singing in the church and for reading in the refectory and at Collation. He had personally to see that the public reader had his volume ready, and that is was replaced in the aumbry at night. To prevent mistakes, as far as it was possible to do, the cantor was supposed to go over the book to be read carefully, and to put a point at the places where the pauses in public reading should be made. It was also his duty as

archivist to enter

the names of deceased members of the community and their relatives in

the necrology of the house, that they might be remembered on their

anniversaries. In this same capacity, at the time of the profession of

any brother, he received from the abbot the written

charter of the vows that had been pronounced, so that the document

itself might be

placed in the archives of the house. He was also required to draw up

the "Brief" or

"Mortuary Roll," wherewith to announce the death of any brother to

other

monasteries, etc., and to ask for

prayers for his soul. This document, often executed in an elaborate

manner and illuminated, after it had received the

sanction of the Chapter was handed to the almoner, who sent it by

special messenger, called

a "breviator," to the other religious houses. In like manner the

cantor

received from the almoner all

such notices of deaths as came to hand, and presented them to the

conventual Chapter to obtain

the suffrages asked for. If, as was frequently the case, the roll had

to be endorsed with the name of the

monastery, with the assurance of prayers, or some Latin verses in

praise of the

dead or expressive of sympathy with the living at the loss, it was the

precentor's duty to see that all this was done fittingly before the

roll was committed again into the almoner's hand to be returned to the

"breviator" by whom

it had been brought.

The cantor also was one of the three custodians of the convent seal, and he held one of the three keys of the chest which contained it. When the die, often in the shape of single or double mould, was needed for the purpose of sealing a document he was responsible for bringing it to the Chapter with the necessary wax in order ---64---  [Illustration: Heading of a Mortuary Roll, Thomas Brown, Bishop of Norwich, d. 1445.] [Download 1,400KB jpg.] ---blank page not numbered-- to affix the common seal to the document, in the presence of the whole convent, and for then returning it to its place of safe custody. Such an important office as

that of precentor obviously required many high

qualities for its due discharge. According to one English Custumal, he

should "ever comport himself with

regularity, reverence, and modesty, since his office, when exercised

with the characteristic virtues,

is a source of delight and pleasure to God, to the angels, and to men.

He should bow down before the altar with all

reverence ; he should salute the brethren with all respect ; he should

in walking

manifest his modesty ; he should sing with such sweetness,

recollection, and devotion

that all the brethren, both old and young, might find in his behaviour

and

demeanour a living pattern to help them in their own religious life and

in

carrying out the observances required by their Rule from each one."

The succentor, or sub-cantor, was the cantor's assistant in everything.When the precentor was absent he took his place and performed his duties. In ordinary course he regulated the singing on the left-hand side of the choir, and attended to such details of the cantor's administration as might be committed to him. It was part, however, of his own duty, as fixed by rule, to see that all the brethren who were tabulated for any duty, or who were involved in any change made in the daily tabula, had knowledge of it, in order to prevent the possibility of mistakes, which would interfere with the solemnity of the divine service, and by such carelessness manifest a want of that respect due to the community as a body. Moreover, before the morning Mass and the High Mass ---65--- the succentor was to be at hand to point out to the celebrants the Collects that had to be said in the Holy Sacrifice, and the order in which they came. If, whilst at the altar, notwithstanding all his care, the priest could not find the proper place, or made delay from some other reason, he was at once to come to his assistance. Lastly, to take one more instance of the succentor's duty : if during the course of the night Office he should see any of the brethren drowsy of forgetting to recite, it was his duty to take his lantern and go towards them, in order to remind them that they were to be more alert as "watchmen keeping their vigil in the Lord's service." Next

in importance to the office of cantor, especially in regard to the

church services which formed so integral a part in the daily life of a

monastery, was

the sacrist. To him, with his several assistants, was committed the

care of the church fabric, with its

sacred plate and vestments, as well as of the various reliquaries,

shrines, and

precious ornaments, which the monastery possessed. It was his duty to

provide for the cleansing and lighting

of the church, to prepare the choir and altars for the various

services, to see that

on feast days they were decked out with the appropriate hangings and

ornaments ;

to provide that the vestments for the sacred ministers were ready for

use

as required, and that, on days when the community were vested in albs

or

in copes, these were rightly distributed to the brethren. The

High Altar was specially in his own personal care : he had to see

that it was becomingly decked for the great feasts, and he was

particularly enjoined never to leave it without a frontal of

---66--- some kind, that he might not seem to neglect the place where the daily Sacrifice was offered. Upon the sacrist was especially

enjoyed the necessary virtue of cleanliness. Every Saturday he had to

see that the sconces of the candlesticks were all scoured out, and that

the pavements before

the altars were washed and cleaned. The

floor of the presbytery was, like the High Altar, to be his own special

charge. He was directed constantly to change the

linen clothes of the altar and all those otherwise used in the Holy

Sacrifice, remembering as a guiding principle that it was "unbecoming

to

minister to God, with things unsuitable for profane use." The

corporals he was also to wash and prepare himself, polishing them

with a stone, known as lisca "lischa," or

glass-stone.

For this and the making

of the altar breads--concerning which work the minute legislation of

the

Custumals testifies to the care required in the production of the bread

for the

Holy Eucharist--the sacrist and his assistants had to be vested in albs

and were required to take every precaution in order to secure spotless

cleanness

of hands and person. During the operation psalms

and other prayers were to be said. Once a week, also on Saturdays, if

he were a priest or a deacon, the sacrist was ordered to wash

thoroughly all the chalices and sacred vessels used at

the Holy Sacrifice, and to see that no stains of wine, or marks of use,

were

left on them. If he were not in Sacred Orders he

had to get one of the brethren who was to do this office for him. On

the Wednesday of each week all the cruets

were to be thoroughly cleansed at the lavatory, as also all the jugs

and

utensils under his care or belonging to his office.

Another function of the sacrist was the care of the ---67--- cemetery where the dead

brothers were laid to their last rest. He was to

keep it neat and tidy, with the grass cut and trimmed, and the walks

free from

weeds. No animals were ever to be allowed to feed among the graves or

to disturb the peace of

"God's acre." This evidence of his care was intended to

show to all that it was here that the bodies of the holy departed were

laid to their peaceful repose to "await the day of the great

Resurrection." In some places the

sacrist also had care of the bells, especially of those which summoned

the brethren to the

church ; and of the clock, where there was one, and this last could be

touched by no

one but himself or one of his assistants on any pretence whatsoever.

Perhaps his most important duty, however, was that of looking after the lighting of the entire establishment. His offices in this matter, somewhat curiously as it may appear to us, was not confined to the church ; but from him the officers of other departments had to obtain the candles or to the light they needed. He had to purchase the supply of wax for making the best candles, and the tallow or mutton fat for the cressets and the commoner sort of lights, together with the cotton for making the wicks. At certain periods of the year, it was his province to hire the itinerant candle-makers and, having provided the necessary material, to preside over the process of manufacturing the waxen and other lights that would be needed by the community. For his store he had to supply the church with all necessary lights for the altars, for the choir, and for illuminating the candle-beams and candelabra on feast days. To light up the dormitory and church cloister, the sacrist had to rise before the others were called for Matins, so that all might be in readiness ---68--- for beginning of the service.

For those who had to read the Lessons, he was warned to provide plenty

of lights, especially in view

of the difficulty experienced by "old men and those with weak

sight," if the light was poor. Moreover, he had to furnish the

novices,

who as yet did not know the psalms by

heart, with candles to read by. At Matins, he himself was always to

have a lighted lantern ready in case of any

difficulty, and at the verse of the Te Deum, "The

heavens and the earth are full of Thy glory," he took this lantern

and,

going to the priest whose duty it was to read the Gospel, bowed, and

gave it

to him so that he might hold it to throw its light on the sacred text.

At the conclusion of Matins he received back

his lantern, and going out from the choir rang the bells for Lauds.

For the use of the monastery, as has been said, the sacrist had to find the material for lighting the cloister. When it was dark he had to light the four cressets, or bowls of tallow with wicks, which, one in each part of the cloister, can have done very little more than help to make the darkness visible. When more light was needed the sacrist found tallow or wax candles for particular purposes. He did the same in the church, where also great cressets, one in the nave, one at the choir-gates, one at the steps of the sanctuary at the top of the choir, and one in the treasury, were always kept burning during the hours of darkness. Moreover, the sacrist had to furnish the two candles for the abbot's Mass, and to give a certain specified amount of wax to each of the community to make their candles. At St. Augustine's, Canterbury, and Westminster, for instance, the abbot had to receive 40 lbs. of wax for his yearly supply of candles ; ---69--- the prior had 15 lbs. ; the

precentor, 7 lbs. ; each of the senior priests, 6 lbs. ; and the

juniors, 4 lbs. He had likewise to find all the

candles necessary to light the refectory and chapter-room, and to give

the cellarer and the infirmarian what they needed for the purposes of

their offices. In winter, after the evening Collation, the sacrist

waited in the chapter-room after the community, standing aside

and bowing as they passed out. When all had departed, he extinguished

the lights and locked the door. As one amongst the many minor duties of

his

office, the sacrist had each Sunday to obtain from the cellarer the

platter of salt to be blessed for the holy water. For

this he could either himself enter the kitchen, otherwise out of the

enclosure, or send another to fetch it. After the Sunday blessing of

the salt, he was himself to

place a pinch of the blessed salt in every salt-cellar used in the

refectory.

In brief, the sacrist, as one of the English Custumals has it, "should be of well-tried character, grave at his work, faithful in all his duties, careful in keeping the brethren to traditions, and watchful over the things committed to his care." "If he love our Lord," says another, "he will love the church, and the more spiritual his office is, the more careful should he be to make the church becoming and attractive for use, and to study to make it in every way more fitting" to be called "the House of God." The sacrist in most of the greater monasteries appears to have had under him four principal assistants : the sub-sacrist, called in some places the secretary, in others the matricularius, and in others, again, the master of works ; the treasurer ; the revestiarius ; and the assistant ---70--- sacristan. The first named, the

secretary, had charge of the offerings made to the church, and was to

look after the fabric of

the church. He was entrusted also with the general bell-ringing, and

was exhorted by the Custumals to endeavour to

study to master the traditional system of the peals, which in most

monasteries was

very elaborate. The secretary also had to see that wine was provided

for the altar, and that a supply of

incense was procured with it was needed ; also that the store of

charcoal, wax, and tallow was

replenished and not allowed to fall too low. He had to purchase these,

and the materials, such as lead,

glass, etc., for the repair of the fabric, at the neighbouring fairs ;

and he was warned to

keep and eye to the building so that it might not suffer by neglect.

Besides these duties, he was the official chiefly concerned in the opening and closing of the church doors at the appointed times, and in seeing to the safe custody of the monastic treasures. For this purpose, he with two other under-sacristians always slept in the church, or close at hand, whilst the treasurer and one other monk slept in the treasury, and even took their meals near at hand, so that the church was never left without guardians either day or night. The revestiarius, as his name implies, was mainly concerned with the vestments, the copes, albs, curtain, and other hangings belonging to the church. He was responsible for their care and mending, and for setting them out for use according to their proper colour, and as their varied richness was appropriate to the order and dignity of the ecclesiastical feasts. By his office he was also charged with giving the albs to the brethren when ---71--- they were vested in them, and

also with bringing to the precentor in the choir sufficient copes for

him to distribute one to each of the community on festivals when the

office

was celebrated in cappis ; or at other

times to the schola cantorum, who

assisted him in the singing or the lectern.

The treasurer was appointed for the purpose of looking after the shrines, the sacred vessels, and other church plate under the orders of the sacrist. He assisted also in other duties of the sacrist as he might be required ; for example, after Compline, he, with the others, when the community had retired to bed, prepared whatever lights would be necessary for the night office. Several times a year it was the general duty of the officials of the sacristy to sweep the church and remove the hay with which it was mostly carpeted, and to put fresh hay in its place. Once a year also they had to find new rush mats for the choir, for the altars, for the steps of the choir, to place under the feet of the monks in their stalls, and before the benches, and at the reading-place in the chapter-house. Various farmsteads, belonging to the monastery, were usually bound at certain times to find the hay, straw, and rushes necessary for this part of the sacrist's work. The cellarer was the monastic

purveyor of all foodstuffs for the community.

His chief duty, perhaps, was to look ahead and to see that the stores

were not

running low ; that the corn had come in from the granges, and flour

from the

mill, and that is was ready for use by the bakers ; that what was

needed of

flesh, fish, and vegetables for immediate use was ready at hand. He had

to

---72--- provide all that was necessary

for

the kitchen ; but was to make no great purchases without the knowledge

and consent of the abbot. In some places it was enjoined that every

Saturday he was to consult with the prior as to the

requirements of the coming week, so as to be prepared with the changes

of diet associated by custom with certain times and feasts.

To procure the necessary stores, the cellarer had of course to be frequently away at the granges and at neighbouring fairs and markets ; but he had to inform the abbot and prior when he would be absent, and to leave the keys of his office with his assistant. As the "Martha" of the establishment always busy with many things in the service of the brethren, he was exempt from much of the ordinary choir duty, but when not present at the public Office, he had to say his own privately in a side chapel. He did not sleep usually in the common dormitory, but in the infirmary, as he was frequently wanted at all hours. As part of his duty the cellarer had charge of all the servants, whom he alone could engage, dismiss, or punish. He presided at their table after the conventual meals, unless he had to be present in the abbot's chamber to entertain guests, when the under-cellarer took his place. At dinner, the cellarer stood by the kitchen hatch to see the dishes as they came in, and that the serving was properly done. On days when the community had dishes of large fish, or great joints of meat, or other portions from which many had to be served before the dinner, the dishes, after being divided in the kitchen, were set in the vestibule of the cellarer's office and there the prior inspected them to see that the portions were ---73--- fairly equal. At supper it was his duty to serve out the cheese and cut it into pieces for the brethren. In the case of Westminster and

St. Augustine's, Canterbury,

the cellarer was urged to look well to the supply of fish, both fresh

and

salt. In the case of the first, he was to be careful that it had not

been caught longer than a couple of days

or so, and that is was always properly cooked. In

regard to all the meals he was to see that the cooks were prepared

and in time with their work, since, says the Custumal, "it were better

to let the cook wait to serve the dinner, than to oblige the brethren

to sit

wanting for their meal."

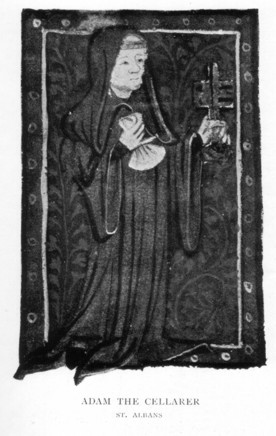

In Benedictine Monasteries, on those days when, in the daily reading of the Rule, the part dealing with the duties and qualifications of the cellarer was read, he was supposed to furnish something extra to the brethren in the refectory. On those occasions he was to be present when the passage of the Rule was read out, and to make sure that he might not be away, was to ask the cantor to let him know a few days beforehand. Besides the main part of this office as caterer to the community, on the cellarer devolved many other duties. In fact, the general management of the establishment, except what was specially assigned to other officials, or given to any individual by the superior, was in his hands. In this way besides the question of food and drink, the cellarer had to see to fuel, the carriage of goods, the general repairs of the house, and the purchases of all materials, such as wood, iron, glass, nails, etc. Some of the Obedientiary accounts which have survived show the multitude and variety of the cellarer's cares. At one time, on one such Roll, beyond the ordinary expenses ---74---  [Illustration: Adam the Cellarer.] [Download 815 KB jpg.] --page not numbered.-- there is noted the purchase of

three hundred and eighty quarters of coal for the kitchen, the carriage

of one hundredweight of wax from London, the process of making torches

and

candles, the purchase of cotton for the wicks, the employment of women

to make

oatmeal, the purchase of œblanket-cloth for jelly strainers,

and the employment of "the

pudding wife on great feast days to make the pastry." He had, of

course, frequently to visit the

granges and manors under his care, to look that the overseer knew his

business

and did not neglect it, to see that the servants and labourers did not

misconduct themselves, and that the shepherds spent the nights watching

with

their flocks, and did not wander off to any neighbouring tavern.

Besides this he was charged to see that the

granary doors were sound and the locks in good order, and in the time

of

threshing out the corn he was to keep watch over the men engaged in the

work and the women who

were winnowing. He was constantly warned by the Custumals that he

should frequently discuss the details of his work

with his superiors, and take his advice, and get to know his wishes.

Finally, in one English Custumal at least, he is warned, in the midst

of all his numberless duties undertaken for the

community, not to let it affect his character as a religious. He should

avoid, his is told, ever getting

into the habit of trafficking like a tradesman, of striving too eagerly

after

some slender profit, or of grinding out a hard bargain from those who

could ill afford it.

As chief assistant the cellarer had an under official, called the sub-cellarer, who was told to be kind and to possess polished manners. Besides taking the chief's place when occasion required, in most well-regulated ---75--- religious establishments

certain

ordinary duties were assigned to the sub-cellarer. They were mainly

concerned with the important

matters of bread and beer. He kept the

keys of the cellar, and drew the necessary quantity of beer before each

meal. When he took his place in the refectory he

handed his keys to the cellarer, in case anything should required

during the meal. He was specially charged with

seeing that the cellar was kept tidy, and that the jugs and other

"vasa ministerii" were clean. When the barrels were

filled with new beer,

they were to be constantly watched by him for fear of an accident. In

winter he was to see that straw or hay

bands were to be placed round the vats to protect them from frost, and

that, if

need be, fires were lighted ; in summer he should have the windows

closed with

shutters, to keep the cellar cool. He was not to serve any beer till at

least the fourth day after it had

been made.

His special help, in seeing to the bakery and the bread, was the granatorius, or guardian of the grain. It was his duty to receive the grain when it came from the farms, and to note and check the amounts, to see to the grinding, and to superintend the bakery. He had to watch that the flour was of the proper quality, and on feast days he was supposed to give a better kind of bread and a different shape of loaf. At times the community might have hot bread "a special treat" and if it were not quite ready, the meal could be delayed for a short time on such occasions. The granator was supposed to visit the manors and farms several times in the year, to estimate the amount of flour that would be required, and to determine whence it was to be furnished, and when. Under the assistant-cellarer and the granator were several official servants, of ---76-- whom the miller, the baker, and

the brewer were the chief. It was the

sub-cellarer's place to entertain any tenants of the monastic farms who

might

come on business, or for any other reason, to the monastery ; and from

him any

of the monks could obtain what was necessary to entertain their

relatives or

friends when they visited them, or the small tokens of affectionate

remembrance, called exennia, which

they were permitted to send them four times in the year.

The refectorian

had charge of the refectory, or as it is sometimes called, the frater,

and had to see that all things were in order for the meals of the

brethren. He should be

"strong in bodily health," says one Custumal, "unbending in his

determination to have order

and method, a true religious, respected by all, determined to prevent

anything

tending to disorder, and loving all brethren without favour." If

duties of this office required it, he

might be absent from choir, and each day after the Gospel of the High

Mass he had

to leave that church and repair to the refectory, in order to see that

all was

ready for the conventual dinner, which immediately followed the Mass.

Out of the revenues attached to his office, the refectorian had to find all tables and benches necessary, and to keep them in repair ; to purchase what cloths and napkins, jugs, dishes, and mats might be required. Three times a year he received from the monastic farms five loads of straw, to place under the feet of the brethren when they were sitting at table, and the same quantity of hay to spread over the floor of the refectory. Five times a year he had to renew the rushes that were strewn about the hall ; and ---77--- on Holy Saturday, by custom, he

was supposed to scatter bay leaves to scent the air, and to give a

festal spring-like appearance to the place. In summer he might throw

flowers about, with mint and fennel, to purify

the air, and provide fans for changing and cooling it.

In preparation for any meal, the refectorian had to superintend the spreading of the table-cloths; to set the salt and see that it was dry ; to see that in the place of each monk was set the usual loaf, that no wood-ash from the oven was on the underside of the bread, and that it was covered by the napkin. The drink had to be poured into jugs, and brought in, so as to be ready before the coming of the community ; and on the table the cup of each monk was to be set at his place. In some houses the spoons also were distributed before the commencement of the meal ; but in others, after the food had been brought in, the refectorian himself brought the spoons and distributed them, holding that of the abbot in his right hand a little raised, and the rest in his left hand. Both cups and spoons were to be examined and counted every day by the refectorian, and he had to repair them when necessary, and see that they were washed and cleaned every day. Amongst the refectorian's other duties may be mentioned his care of the lavatory. He was to provide water--hot if necessary--for washing purposes, and was to have always a clean hanging-towel for general use, as well as two others always ready in the refectory. All towels of any kind were to be changed twice a week, on Sundays and Thursdays. The refectorian was to be blamed if the lavatory was not kept clean, or if grit or dirt was allowed to collect in the washing-trough. He had to keep in the ---78--- lavatory a supply of sand and a

whetstone for the brethren to use in scouring and sharpening their

knives. When the abbot was present at meals, he had

to see that the ewer and basin with clean towels were prepared for him

to wash

his hands. On Maundy Thursday the tables were to be set with clean

white cloths, and a caritas,

or extra glass of wine, was to be given to all the community. At the

approach of All Saints

the refectorian had to see that the candlesticks were ready for the

candles to

light the refectory ; one candlestick being provided for every three

monks at

the evening meal from November 1 to the Purification--February 2.

Lastly, it was the refectorian's duty

to sample the cheeses intended for the community. He could taste two or

three in a batch, and if he did not

like them reject the whole lot. At Abingdon a œweight

of cheese was equal to eighteen stone, and such a œweight was

supposed to last the community five days!

The office of kitchener was

one of great responsibility. He was

appointed in Chapter by the abbot with the advice of the prior, and he

should

be one who was agreeable to the community. According to the Custumal of

one great English abbey, the kitchener was to be almost a paragon of

virtue. He ought to be œa truly religious man, just, upright, gentle,

patient, and trustworthy. He should be ready to

accept suggestions, humble in his demeanour, and kind to others. He

should be known to be of good disposition

and conversation ; always ready to return a mild answer to those who

came to

him. He was œnot to be lavish, nor too niggardly, but ever to keep the

---79--- happy mean in satisfying the

needs of his brethren, and in his gifts of food and

other things to such as made application to him. And as the safeguard

of all the rest, he should strive ever to keep his

mind and heart in peace and patience.

The needed to be well instructed in the details of his office. he had to know, for example, how much food would be required for the allowances of the brethren, in order to know what and how much to buy, or to obtain from the other officials. he was to have what help he needed, and, besides the cooks, he had under him a trustworthy servant, sometimes called his emptor, or buyer, who was experienced in purchasing provisions, and knew how and at what seasons it were best to fill up the monastic store-houses. It was obviously of great importance, in order to prevent waste, that the kitchener should keep a strict account of what was expended in provisions and of what amounts were served out to the brethren. Each week he had to sum up the totals, and at the end of the month he had to present his accounts for examination to the superior, being prepared to explain why the cost of one week was greater than that of another, and in general to give an account of his administration. As his name imported, the kitchener presided over the entire kitchen department. he was directed to see that all the utensils made use of were cleaned every day. He was to know the number of dishes required for each portion, and to furnish the cook with that number ; he was to see that food was never served to the community in broken dishes, and was to be particular that the bottoms of the dishes were clean before allowing them to leave his charge, so that they might not soil the napery on the ---80--- refectory tables. Whilst any

meal was being

dished, he was to be present to prevent unnecessary noise and clatter,

and he was to see that the cooks got the food ready in time, so that

the

brethren might never be kept waiting. If the High

Mass and Office, preceding the dinner, were for any reason protracted

beyond

the usual time, the kichener was to warn the cooks of the delay. In the

refectory his place was opposite to

that of the prior on the left, but if there were need, he could move

about

during the supper and arrange or change the portions. In a special

manner he was to see to the

sick, and serve them with food that they might fancy or relish or that

what was

good for them.

In some places the office of kitchener, like many of the others, was endowed with special revenues which had to be administered by the kitchener. At Abingdon, for example, the rents of many of the town tenements were assigned to it. From his separate revenue the abbot in the same place paid into the kitchener's account more than £100 a year, to meet the expenses of his table, chiefly in the entertainment of guests. Besides money receipts, in most monasteries there were many payments in kind. In the same abbey, to take that place as a sample, at the beginning of Lent various fisheries had to supply so many "sticks of eels." So, too, on the anniversary of Abbot Watchen, the kitchener had the fish taken from the fish-stew at one of the monastic manors ; and during Lent, from every boat which passed up the Thames carrying herrings, except it were a royal barge, the ktichener took toll of a hundred of the fish, which had to be brought to him by the boat's boy, who for his personal service received five herrings and a jug of beer. ---81--- The character of the religious kitchener as sketched in one English Custumal is very charming. "He

should be humble at heart and not merely in word ; he should possess a

kindly

disposition and be lavish of pity for others ; he should have a sparing

hand in

supplying his own needs and a prodigal one where others are concerned ;

he must

ever be a consoler of those in affliction, a refuge to those who are

sick ; he

should be sober and retiring, and really love the needy, that he may

assist

them as a father and helper ; he should be the hope and aid of all in

the

monastery, trying to imitate the Lord, who said, 'he who

ministers to

Me, let

him follow Me.'"

---82--- The long list of duties for the kitchener to attend to set forth in the monastic Custumals, and the grave admonitions which accompany them, show how very important a place that official occupied in the monastery. He had to attend daily in the larder to receive and check the food. When the eggs were brought, for example, by the œvitelers, he had to note who brought them, and whence they came, and to settle how they were to be used. He was to see that the paid œlarderer had meat and fish, salt and fresh, and that the fowls and other birds were fed whilst they were under his charge, waiting for the time why would be wanted for the table. After having made his daily inspection of the outer larder, the kitchener was to visit the inner larder, in order to see that all the plates and dishes were properly scoured, that all the food ready for cooking was kept sweet and clean, and that all the fish was well covered with damp reeds to keep it fresh. Moreover, he was to inspect the fuel, to see that the supply was always kept up by the doorkeeper of the kitchen, with the help of the turnbroach. The kitchener was warned, not

without reason, no doubt, to be careful about his keys. They

were to be kept in his room, and no one might touch them without

having first obtained his leave. "And," says the Custumal, "he should

prudently take heed not to put

too much trust in the cooks and the servants, and on account of the

danger of temptation

should not let them have his keys without going personally to see what

they wanted

them for." In this way only was it

possible to guard against waste and alienation of the monastery goods.

In discharge of his duties, which were exercised for the common good, the kitchener might easily be excused from choir duties. During the morning Office he was permitted, for example, to say his Mass, and his first daily duty was to visit the sick to see if there were anything that would relish that he could get, and to cheer them with a few kindly words. Among the many things that the kitchener might be called upon to provide at various times for the brethren, it may be mentioned that he had to furnish the cantor with some of the best beer when he desired to mix the ink for the writers. 6. THE WEEKLY SERVERS IN THE KITCHEN Closely connected with the

office of kitchener

is that of the weekly servers, for they were among his chief, though

constantly changing, assistants. They entered upon

their weekly duties on the Sunday after Lauds, when those who were

finishing their week and those who were beginning had to ask and

receive the

triple blessing. Immediately after receiving

the benediction, the new officers went to their work. They drew water

to wash with, and

---83--- after their ablutions went to the kitchen to be ready to do whatever might be needful. During their week of service,

if there were two Masses, one server went to the

first, the other to the second. Whilst the

community were in the cloister at reading-time, both were to be at work

in the kitchen. They had to be in the refectory

ready to serve at meal times, and before all refections they were to

see that the lavatory was prepared for the brethren. If

there were a frost they had to provide basins of hot

water and put them near the washing-place, and they were to make ready

the water,

towels, and other things requisite on shaving days. After

each meal one of the weekly servers in an apron went to the

kitchen to assist in washing up the dishes and plates.

On Saturdays they had to

prepare hot and cold water, with towels, in the

cloister, for the weekly feet-washing ; to clean out the lavatory and

scour the

pot used for boiling water in the kitchen ; to

help to sweep up and tidy the kitchen, and to prepare wood for the fire

next day. In the evening, as the last day of their weekly service, they

performed the mandatum,

or feet-washing : the first server washed the feet of the brethren,

beginning with those of the abbot, and the second wiped them with the

towels he

had already dried and warmed. As a last act

they returned and accounted for all the vessels and other things they

had received when entering upon their duties on the previous Sunday.

---84--- -end chapter- |

| Historyfish

pages, content, and design copyright (c) Richenda

Fairhurst, 2008 All rights reserved. No commercial permissions are granted. The Historyfish site, as a particular and so unique "expression," is copyright. However, some (most) source material is part of the public domain, and so free of copyright restrictions. Where those sections are not clearly marked, please contact me so I can assist in identifying and separating that material from the Historyfish site as a whole. When using material from this site, please keep author, source, and copyright permissions with this article. Historyfish intends to generate discussion through shared information and does not claim to provide, in any way, formal, legal, or factual advice or information. These pages are opinion only. Opinions shared on historyfish are not necessarily the opinions of historyfish editors, staff, owners or administrators. Always consult proper authorities with questions pertaining to copyrights, property rights, and intellectual property rights. It is my intent to follow copyright law (however impossibly convoluted that may be). Please contact me should any material included here be copyright protected and posted in error. I will remove it from the site. Thank you. |