|

|

Public Domain text

transcribed

and prepared "as is" for HTML and PDF

by Richenda Fairhurst, historyfish.net. July 2007. No commercial permissions granted. Text may contain errors. (Report errors to  ) ) |

CHAPTER IV

The

official appointed to have the care of the infirm and sick should have

the

virtue of patience in a pre-eminent degree. “He

must be gentle,” says one Custumal, “and

good-tempered, kind,

compassionate to the sick, and willing as far as possible to gratify

their

needs with affectionate sympathy.” When

one of the brethren was seized with any sickness and came to the

infirmary, it

was the infirmarian’s first duty to bring thither the sick man’s plate,

his

spoon and his bed, and to inform the cellarer and kitchener, so that

the sick

man’s portion might be assigned to him in the infirmary refectory.

Whenever

there were sick under his charge the infirmarian was to be excused, as

far as

was necessary, from regular duties. He

said Mass for the sick, if he were a priest, or got some priest to do

so, if he

were not. If the sick were able to

recite their Office, he said it with them, provided lights, if

necessary, and

procured the required books from the church. Whatever

volumes they needed for reading he borrowed from

the aumbry in

the cloister ; but he was warned always to take them back again before

the

cantor locked up the cupboard for the

---85--- night. If there were more than

one monk sick at the

same time and they could help themselves, the infirmarian was then to

go to the

regular meals in the refectory ; but he was to return to his charges as

soon as

possible and see that they had been properly served. He always slept in

the infirmary, even when

there were no sick actually there, and this because he was always to be

ready

for any emergency. Out of the revenue

assigned to his office he had to find whatever might be necessary in

the way of

medicine and comforts for the sick. He

was charged to keep the rooms in the infirmary clean, the floors

sparsely

covered with fresh rushes, and to have a fire always burning in the

common-room

where it was needed. According to one

set of English directions, the infirmarian was advised always to keep

in his

cupboard a good supply of ginger, cinnamon, peony, etc., so as to be

able at

once to minister some soothing mixture or cordial when it was required,

and to

remember how much always depended in sickness on some such slight act

of

thoughtful sympathy and kindness.

The medieval rules of the

infirmary

will probably strike us, with our modern notions, as being strangely

strict

upon the sick. The law of silence, for

instance, was hardly relaxed at all in the infirmary ; the sick man

could

indeed talk about himself and his ailment and necessities to the

infirmarian at

any time, and the latter could give him every consolation and advice ;

but

there was apparently no permission for general conversation even among

the

sick, except at the regular times for recreation ; even at meal times

the

infirm ate in silence and followed, as far as might be, the law of the

convent

refectory.

---86---  [Illustration: Infirmarian St. Alban's] [Download 821KB jpg] ---87--- The brethren who were unwell

were

not all received in the infirmary of treatment.

here

were some monks sick, as one set of regulations

points out, who

were ailing merely from the effect of the every monotony and the

necessarily

irksome character of the life in the cloister ; from the continued

strain of

silence ; from the sheer fatigue of choral duties, or from

sleeplessness and

such like causes. These did not need any

special treatment under the infirmarian’s care ; they required rest,

not medicine

; and the best cure for them was gentle exercise in the open air, in

the garden

or elsewhere, with temporary freedom from the strain of their daily

service. Those who had grown old in their

monastic service were to find a place of rest in the infirmary, where

they were

to be specially honoured by all. They

too, however, had to keep the Rule as far as they were able without

difficulty,

and were to remember, as on English Custumal reminds them, that not

even the

pope could grant them a dispensation contrary to their vows.” So they

had to keep silence for instance, if

possible, and especially the great night silence after Compline.

The curious practice of

periodical

blood-letting, regarded according to medieval medical knowledge as so

salutary,

formed part of the ordinary infirmarian’s work.The

operation was performed, or might be performed, on

all, four times a

year, if possible in February, April, September, and October. It was

not to take place in the time of

harvest, in Advent or Lent, or on the three days following the feast of

Christmas, Easter, or Pentecost. The

community were operated upon in batches of from two to six at a time,

and the

special day was arranged for them by the superior in Chapter, who would

---88--- announce

at the proper time that “those who sat at this or that table were to be

blooded.” In settling the turns,

consideration had, of course, to be paid to the needs of the community.

The weekly server, for example, and the

reader, and the hebdomadarian of the community Mass were not to be

operated

upon during the period of their service ; and when a feast day was to

be kept

within four days of the blood-letting, only those were to be practiced

on who

could be spared from the singing and serving at the necessary

ecclesiastical

functions of the feast.

From first to last, the operation of blood-letting occupied four days, and the process was simple. At the time appointed, the infirmarian had a fire lighted in the calefactory, if it were needed, and thither, between Tierce and Sext, if the day were not a fast, or between Sext and None if it were, the operator and his victims repaired. If the latter desired to fortify themselves against the lancet, they might proceed beforehand to the refectory and take something to eat and drink. During the time of the healing, after the styptic had been applied and the bandages fastened, the discipline of the cloister was somewhat mitigated. The patient, for instance, could always spend the hours of work and reading in repose, either lying on his bed or sitting in the chapter-room or cloister, as he felt disposed. Till his return to full choir work, he was not to be bound to any duty. If he were an obedientiary or official, he was to get someone to see to his necessary duties for him during the time of his convalescence. If he liked to go to the Hours in choir, he was to sit ; he was never to bend down or do penance of any kind, for fear of displacing the bandages, and he was to go out of the church before the others, for ---89--- fear of having his arm rubbed if he were to walk in the ranks. During the three days of his convalescence he said his Compline at night in the chapter-room or elsewhere, and then went straight to bed before the community. Though he had still to rise for Matins with the others, after a brief visit to the church he was allowed to betake himself to the infirmary and there to say a much shortened form of the night Office with the infirmarian and others. When this was done he was to return at once to bed. In the refectory the monk who had been “blooded” received the same food as the rest, with the addition of a half-pound of white bread and an extra portion, if possible, of eggs. On the second and third days this was increased in amount, and other strengthening food was given to him. In some places these meals were served in the infirmary after the blood-letting ; and it was directed that the infirmary servant should on the first day after the bleeding get ready for the patients sage and parsley, washed in salt and water, and a dish of soft eggs. Those who found it necessary to be cupped or scarified more frequently, adds one set of regulations, had to get leave, but were not to expect to stay away from regular duties on that account. The

conventual almoner was not necessarily a priest ; and although, as his

name imports,

his chief duty was to distribute the alms of the monastery to the poor,

there

were generally many other functions in behalf of the brethren, which he

had to

discharge.

“Every almoner must have his heart aglow with charity,” says one writer. “his pity would know no bounds, and he ---90--- should

possess the love of the others in a most marked degree ; he must show

himself

as the helper of orphans, the father of the needy, and as one who is

ever ready

to cheer the lot of the poor, and help them to bear their hard life.”

In order to distribute the alms of the house the almoner might be absent from the morning Office, and although he should be discreet and careful in his charities, not wasting the substance of the monastery, he should at the same time be kind, gentle, and compassionate. He would often visit the aged poor and those who are blind or bedridden. If amongst his numerous clients for assistance he ever found some who, having been rich, had been brought to poverty, and were perchance ashamed to sit in the almonry with the other poor, he should respect their feelings, and should try and assist them privately. he should submit without manifesting any sign of impatience to the loud-voiced importunity of beggars, and must on no account abuse of upbraid them, “remembering always that they are made to the image of God and redeemed by the blood of Christ.” The general measures for the

relief

of poverty were in the hands of the almoner ; but he is told that

should he

find that his charity to any individual was likely to be continuous, he

must consult

the superior ; and in like manner, when anyone has been a pensioner of

the

house, the almoner must not stop the usual relief without permission.

Whilst engaged with Christ’s poor in the

almonry, in ministering to the wants of the body, he should never

forget those

of the soul, and should, as a priest, when opportunity served, speak to

them

about spiritual matters, of the need of Confession and the like. He had

charge

of all the old clothes of the religious, and

---91--- could

distribute them as he though fit, and before Christmas time he was

enjoined not

to omit to lay in a story of stockings, etc., so as to be able to give

them as

little presents to widows, orphans, and poor clerks.

To the office of almoner belonged the remnants of the meals in the refectory, the abbot’s apartments, the guest-house and the infirmary. At the close of every meal one of the weekly servers took round a basket to collect the portions of bread, etc., which the monks had not consumed, and after the dinner the almoner could himself claim, as left for him, anything that was not guarded by being covered with a napkin. In many places, on the death of a monk, it was the almoner’s duty to find the community an extra portion for the labour involved in the long Office for the dead, and to remind them to pray for the soul of the deceased. In some monasteries, on the other hand, the almoner daily received a loaf and one whole dish of food that the poor person who received it might pray for the founder of the monastery. In most houses, too, upon the death of any member of the establishment, a cross was put in the refectory upon the table in front of the place where the dead monk had been accustomed to sit, and for thirty days the full meal of a religious was served and given to the poor, that they might pray for the departed brother. The almoner also superintended

the

daily maundy, or washing the feet of the poor selected for that

purpose. At Abingdon, for example, every morning,

after the Gospel of the morning Mass, the almoner went to the door of

the

abbey, and from the number of those waiting for an alms he chose three,

who

subsequently had their feet washed by the abbot, according to the

approved

---92--- custom.

After this maundy they were fed and sent away with a small present of

money. On the great maundy, on the

Thursday before Easter, it was the almoner’s duty to select the

deserving poor

to be entertained—

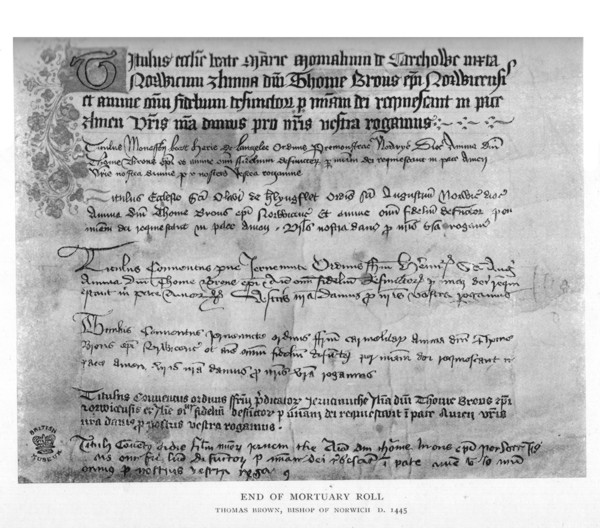

sometimes they were to be equal in number to the number of the community—and after they had had their meal, the almoner furnished each religious with a penny to bestow upon the poor man he had served. As an ordinary part of his office the almoner had also a good deal to do with any monastic school, other than the claustral school for young religious, which was connected with a monastery. There, young clerks were to have free quarters in the almonry, and the almoner was frequently to see them set to argue one against the other, so sharpen their wits. He was to keep them strictly, or , as it was called in those days of belief in corporal punishment, “well under the rod,” and he had to find, out of the revenues of his office, all “discipline rods” both for the boys and for use in the monastic Chapter. In feast days, when there were no regular lessons, these young clerics were to be set to learn the Matins of the office of the Blessed Virgin ; or to practice writing upon scraps of parchment. If they did not learn, and especially if they would not, the almoner was to get rid of them, and fill their places with those who would. As before noted, to the almoner

belonged, at least partially, the duty of attending to the

mortuary-rolls or

notices of deaths. That is to say, he

had to supervise the “breviators,” or letter-carriers, who were sent to

announce the death of the brethren, or who came with such rolls. He

received the rolls and gave them into the

hands of the cantor to copy and to notify to the com-

---93--- munity. If it were the

mortuary-roll of a prelate,

and especially if it announced the death of the head of any associated

monastery, the superior was to be informed at once, in case he should

desire to

add to the roll something special about the dead ; that is, more than

the mere

name of the place, which was simply meant to testify that the bearer of

the

roll was waiting to receive back his “brief,” he was to be entertained

liberally in the almonry. Sometimes the

almoner

was to get the cantor to multiply copies of the death-notice, and these

he at

once dispatched far and wide by the hands of such poor people as were

tramping

the country and called at the monastery for assistance.

Amongst the miscellaneous

duties of

the office of almoner, in some places that official had to see that the

mats

under the feet of the monks in the choir were renewed each year for the

Feast

of All Saints. He had also to find the

rushes for the dormitory floor. From St.

Dunstan’s Day, May 19th, till Michaelmass the cloister was

kept

strewn with green rushes, which the almoner had to find, as well as all

the

mats used in the cloister and on the stairs, and also in some houses

the

bay-leavers or “the herb-benet, or common hedge avens,” to scatter in

the

refectory and cloister at Easter. At the

time of the long processions also on the Rogation days, two of the

almonry

servants, standing at the church door, were want to distribute boxwood

walking-sticks to such of the community who through age or infirmity

needed

them to walk with.

The almoner, says one Custumal,

would remember that from his office might be derived great spiritual

gain.

---94---  {Illustration: Mortuary Roll] [Download 1,500KB jpg ] He should keep before his mind our Lord’s words : “I was hungry, and you gave me to eat,” etc. For this reason alone he should ever be gently and kind to the poor, for in them he was really ministering to the Lord Jesus Christ Himself. He ought to endeavour to be seldom, if ever, without something to give away in charity, and he should try to keep a supply of socks, linen and woolen cloth, and other necessities of life, so that it by chance Christ Himself were at any time to appear in the guise of a poor, naked and hungry man, “He might not have to depart from His own house unfed, or without some clothes to cover the rags of His poverty.” 9. THE

GUEST-MASTER

In medieval days the

hospitality

extended to travellers by the monastic houses was traditional and

necessary. The great abbeys, especially

those situated along the main roads of the country, were the

halting-places of

rich and poor, whom business, pleasure, or necessity compelled to

journey on

“the King’s highway.” For this and many

other causes, such as the coming to the monastery of people desiring to

be

present at church festival and other celebrations, visits of the

relatives of

monks, and of those who were concerned in the business transactions of

a large

establishment, the coming and going of guests was probably of almost

daily

occurrence. The official appointed to

attend to the wants of all these and to entertain them on behalf of the

monastery was the hospitarius or

guest-master.

The official guest-master had the reputation of the religious house in his hands. He required tact, prudence, and discretion in a full measure. Scribbled on the margin ---95--- of a monastic chartulary as a

piece of advice, good indeed for all, but most of all applicable to the

official

in the charge of guests, are the following lines :—

“Si sapiens fore vis, sex serva quae tibi mando Quid dicas, et ubi, de quo, cui, quomondo, quando.” Which may be Englished thus:— “If

thou woulst be wise, observe these six things I command you,

Before speaking think what you say and where you say it ; about and to whom you talk, as well as how and when you are conversing.” On the other hand, the

guest-master

is frequently warned that he must certainly be neither too stand-off,

silent,

or morose in his intercourse with strangers. And,

as it is part of his duty to hold converse with

guests of all sorts

and condition, with men as well a women, “it becomes him,” says one

Custumal,

“to cultivate, “ not merely a facility of expression in his

conversation, but

pleasing manners and a gentle refinement which comes of and manifests a

good

education. All his words and doings

should set the monastic life before the stranger “in a creditable

light,” since

it becomes him to remember the proverb “Friends are multiplied by

agreeable

words, enemies are made by harsh ones.”

The guest-master’s first office

was

to see that the guest-house was always ready for the arrival of any

visitor. He was to make certain that

there was a supply of straw sufficient for the beds ; that the basins

and jugs

were clean inside and out ; that the floors were well swept and spread

with

rushes ; that the furniture was properly dusted, and that, in a word,

the whole house was kept

---96--- free from

cobwebs and from every speck of dirt. Before

the coming of an expected guest the master was

personally to

inspect the chamber set apart for him ; to see that there was a light

prepared

for him should he need it; that the fire did not smoke ; and that

writing

materials were at hand in case they were required.

Moreover, he was to ascertain that all things were ready in the common rooms for his entertainment. When it was necessary to procure something that was needful, the master could enter the kitchen, which was, of course, otherwise out of the enclosure for the monks generally. He was to get coal and wood and straw from the cellarer ; the cups, platters, and spoons that were required from the refectorian ; and the sub-cellarer was to arrange as to the food itself. At Abingdon the guest-master had a special revenue to be spent upon what must have been a source of very considerable expense in those days, the shoeing of the horses of travellers generally who came to the abbey, and especially of those belonging to religious and to poor pilgrims. People also at various times left small bequests for this as for other monastic charities. In the same abbey, the guest-master had also a small yearly sum, charged on a house in the town, which had been left by “Thurstin the tailor,” to help to entertain poor travellers, as a memorial of the day when he and his wife had been received into the fraternity of the monastery. When word was brought to the

guest-master of the arrival of a guest, he was charged forthwith to

leave

whatever he was about, and to go at once to receive him, as he would

Christ

Himself. He was to assure him—especially if he were a stranger—of the

monastic

hospitality, and endeavour from the first to place him at his

---97--- ease. He was to remember what

he would wish to be

done in his own regard under similar circumstance, and what he would

desire to

be done to himself he was to do all guests. “By

showing this cheerful hospitality to guests,” says one

English

Custumal, “the good name of the monastery is enhanced, friendships are

multiplied, enmities are lessened, God is honored, charity is

increased, and a

plenteous reward in heaven is secured.” The

whole principle of religious hospitality, as practiced

in a medieval

monastery, is really summed up in the words of St. Benedict’s Rule : Hospites tamquam Christius suscripiantur—Guests

are to be received as if they were Christ Himself.

Directly the guest-master had cordially received the new-comer at the monastery gate, he was to conduct him to the church. There he sprinkled him with holy water and knelt by him, whilst he offered up a short prayer of salutation to God, into whose house he was to come safely after the perils of a journey. After this the master conducted his guest to the common parlour, and here, if he were a stranger, he begged to know his name, position, and country, sending to acquaint the abbot or superior if the guest was one who, in his opinion, ought to receive attention from the head of the house. When the guest was going to stay beyond a few hours, he was taken after the first and formal reception to the guest-house, where, when he had been made comfortable, according to the Rule, the master arranged for the reading of some passages from the Scriptures or some spiritual work. If the strangers were monks of some other monastery, and the length of their visit afforded sufficient time, he showed them over the church and house, and if they had servants ---98--- and

horses he sent to acquaint the cellarer, that they too might receive

all

needful care. If a conventual prior came

on a visit he was to be given a position and portion of food, etc.,

similar to

that of the prior of the house, and every abbot was to be treated in

all things

by the monks like their own abbot. For

each monk-guest the master got from the sacrist four candles, and the

chamberlain found the tallow for the cressets in the guest-house. It

was the master’s duty to see that the

guests kept the rules, which were to be made known to them on their

first coming. Strangers were entertained

for two days and

nights by the house without question. If

any of them wished to speak with one of the monks, leave had to be

first

obtained from the superior.

When the guest desired to say the Office, books and a light were to be provided in the guest-hall, and the master was to recite it with him if he so desired. If on great feasts guests desired to be present in the church for Matins, the master called them in ample time, waited for them whilst they rose, and then with a lighted lantern accompanied them to the choir. There he was to find them a place and a book and leave them a light to read by. Before Lauds he came to them with his lantern to take them back to their chambers that they might again return to bed till the morning Office. Either the guest-master, or his

servant, had to remain up at night till the fires were seen to be

protected and

the candles put out. If the guest was

obliged

to depart early in the morning, the master had to obtain the keys of

the gate

and of the parlour from the prior’s bedplace. After

having let the visitor out, he was charged to take

care to relock

the doors and to replace the keys. At

all times

---99--- when

guests were leaving the master was bound to be present, and before

wishing them

Godspeed on their journey, he was instructed to go round the chambers,

“in

order,” says on Custumal, “to see that nothing was left behind, such as

a sword

or a knife ; and nothing was taken off by mistake which belonged to his

charge

by his Office, and for which he was responsible.” With

the departure of guests came the duty of

seeing that everything in the guest-house was put in order again, and

was ready

for the advent of others.

chief official duties of the

chamberlain of a religious house were concerned with the wardrobe of

the

brethren. He consequently had to know what and how much clothing each

religious

ought to have by rule, and what in fact he had. For

this purpose he was provided with an official list of

what was

lawful, or required, and from time to time with his servant he had to

examine

the clothing of the monks, removing what was past repair, and

substituting new

garments for the old, which were placed in the poor-cupboard to satisfy

the

charitable intentions of the almoner. In

the distribution of these cast-off clothes, however, it was to be

remembered

that those who worked for the monastery had first claim, if they were

in need,

upon the old garments of the monks which had found their way to the

poor-cupboard.

It is somewhat difficult to

discover

exactly the amount of underclothing considered sufficient for

religious,

especially as in most places there seems to have been little difficulty

in

furnishing more, if there was any particular reason shown for

additional

clothing. Three

---100--- sets, however,

of shirts, drawers, and socks, seem to have been an ordinary allowance

for

priests and deacons, and probably two sets for others; with two tunics,

scapulars and hoods, and two pairs of boots. These

last were over and besides the “night-boots,” which

were

apparently made of thick cloth, with soles of some heavy noiseless

material,

such as our modern felt.

The chamberlain by virtue of

his

office had also to provide the laundresses and superintend their work.

These necessary servants were to mend as well

as wash all sheets, shirts, socks, etc., and all clothes that needed

regular

cleansing and reparation. All

underclothing was to be washed, according to one set of rules, once a

fortnight

in summer, and once every three weeks in winter. Great

care was to be taken that no losses

should occur “in the wash,” and all the clothes sent to the tub were to

be

entered on “tallies,” or lists, and returned in the same way into the

charge of

the official.

The chamberlain, according to

the

amount of his work, could generally have a monk as assistant

chamberlain either

for a time, or continuously. Amongst the

duties assigned to this assistant was that of looking to the repairs

needed in

the clothes, which in a large establishment were sometimes very heavy.

In one of the Custumals, any monk who wanted

a garment repaired, had to place it in the morning in one of the bays

of the

cloister leading to the chapter-house. Thither

each day came the assistant chamberlain to see

what had been placed

there, and what was wanted. He then

carried

what he found to the tailor’s shop and fetched it again when the

repairs had

been executed. This necessary

establishment

was generally well organised. For

example, at Abingdon there were

---101--- four lay

officials and five helpers in the tailor’s department. The first had

charge of the skins and furs ;

the second was the master tailor ; the third the master cutter ; and

the fourth

was called the “proctor of the shop” ; and his office was to see that

all

materials had been supplied by the camerarius, that there was a store

of cloth

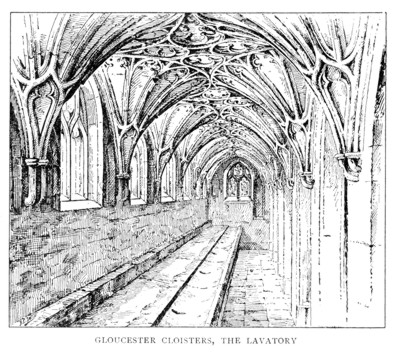

[illustration: Gloucester cloisters, the lavatory] [Download 1,160KB jpg] skins, an abundance of needles,

pins, and thread, and a sufficiency of

knives

and scissors, and wax for the thread. The

proctor of the shop also had charge of the lights and fire, and he

himself

slept in the shop and was responsible for its safe custody.

The camerarius by his office had to provide all the cloth and other material necessary for the house. For such ---102--- purposes

he had to attend at the neighbouring fairs, whither merchants brought

their

goods, where he purchased what was necessary. For

such matters he frequently had the use of a cart and

horse, with its

driver. When vendors of cloth came to

the monastery the chamberlain had to interview them, and, if necessary,

entertain them out of the revenue attached to his office.

In medieval times, when patent methods of heating were unknown and windows were often unglazed or badly glazed, the cold of our northern climate required the general use of skins and furs as lining to the ordinary winter garments for protection from the weather and draughts. The cloister was no exception, especially when the monks had to spend some hours each night in their great unwarmed churches ; and so we find in the Custumals that the camerarius was warned to prepare a store of lamb-skins and cat-skins before the cold set in, and he was granted a special supply of salt for the purpose of curing them. He had charge also of the boots of the community ; and at one place at least, three times in the year he had a right to a supply of pigs’-fat from the kitchener, in order that he might compound the grease with which the community liberally anointed the leather of their boots to keep it supple and to make it weather-proof. On the chamberlain of every monastic house devolved also the duty of making preparation for the baths and for the shaving, etc., of the brethren. He had to purchase linen cloth for the towels in the cloister lavatory, for the monks’ baths, and for the general feet-washing each Saturday. He was charged always to keep an eye upon the lavatory, and, when it was frozen in the winter, he was told to see that there were hot water and warm dry ---103--- towels

for the monks’ use. He had also to buy

the wood needful to warm the water for the baths, which were to be

taken by

all, three or four times in the year ; and he had to keep by him a

store of

sweet hay to spread round about the bathing tubs for the monks to stand

on. From November to Easter he was to

provide hot water for the general feet-washing on Saturday, and on

Christmas

Eve he was charged to see that a good fire was kept burning in the

calefactory,

so that when the monks came out from their midnight Mass and Office,

they

should find a warm room and plenty of hot water to wash in after their

long

cold vigil in the church. For all these

occasions, too, the camerarius had to provide a supply of soap, as well

as for

the washing of heads and for shaving purposes.

In Cluniac monasteries, at least, the arrangements for shaving had also to be made by the chamberlain. The brother who undertook the office of barber kept his implements—razors, strop, soap, and brushes, etc.—in a small moveable chest, which usually stood near the dormitory door. When necessary he carried it down to the cloister, where, at any time that the community were at work or sitting in the cloister, he could sharpen up his razors or prepair his soaps. When the time of the general “rasura” came, the community sat silently in two lines, one set along the cloister wall, the other facing them with their backs to the windows. The general shaving was made a religious act, like almost every other incident of cloister life, by the recitation of psalms. The brothers who shaved the others, and those who carried the dishes and razors, were directed to say the Benedicite together before beginning their work ; all the rest as they sat there during the ceremony, except of course the individual actually being operated ---104--- Verba mea and other

psalms. The sick, and those who had

leave, were shaved apart from the rest in the warmer calefactory. It

would seem that the usual interval between

the times of shaving the monks’ tonsures was about three weeks ; but

there was

always a special shaving on the eve of all great festivals. Sometimes

in monasteries situated in towns

the work of shaving was performed by a paid expert. In the Winchester

chamberlain’s account-roll, there are entries for such payments, as,

for

example “for thirty-six shavings, 4s.6d.”

According to custom, the chamberlain had also to find, out of his revenues, various little sums for specific purposes. For example, from the same Winchester rolls it appears that he paid 20s. to each monk, in three portions of different amounts, apparently as pocket-money ; he also year by year paid the money for wine on Holy Innocents’ Day for the boy-bishop celebration ; he kept several boys in the school, and also defrayed the cost of a student at Oxford University. At Abingdon, in the same way, from rents received by him, the chamberlain had to furnish each of the monks with threepence to give to the poor whose feet were washed on Maundy Thursday. The chief virtues which should characterize the true monastic chamberlain are stated to be, “wisdom and learning, a religious spirit, a mature judgment, and an upright honesty.” The master of the novices was,

of

course, one of the most important officials in every religious house.

So far we have spoken of the obedientiaries,

who were immediately concerned with the management of the whole

monastery ; and

the novice-master is placed here, not because his

---105--- was a

less dignified or a less important office, but because he was

officially

concerned merely with those who were being proved for the religious

life. The master of novices, we are

told, was to

be a man of wide experience and strength of character. “A person fitted

for winning souls,” is St.

Benedict’s description of the ideal novice-master. It is obvious that

he should be able to

discern the sprits and prove them ; to see whether their call to the

higher

life was really from God, or a mere passing inclination or whim.

During the year of his probation the novice was in complete subjection to his master. The postulant, who came to beg for admission into religion, usually remained in the guest-house for four days ; after that time, in some houses, he came to the morning Chapter for three consecutive days, and, kneeling in the midst of the brethren, urged his petition to be allowed to join their ranks and to enter into holy religion in their monastery. After the third morning, if his request was granted, he was clothed in the habit of a monk, and was handed over to the care of the novice-master, who was to train him, and to teach him the practice of the religious life ; whose duty it was to test him and to prove him ; and who, for a whole year, was to be his guide, his master, and his friend. One walk of the cloister, generally the eastern side, was assigned to the use of the novices. In their work and life they were to be separated, as much as possible, from the rest of the community except in the church, the refectory, and the dormitory. Even in these places they were to be still under the immediate control and constant watchful care of their master. From the day of their reception the systematic teaching of the rules ---106--- and

traditional practice of the religious life, which was imparted in the

novitiate,

was commenced. The first lesson given

the novice was how he was to arrange the monk’s habit and cowl, which

were new

to him ; how to hold his hands and head ; and how to walk with that

modesty and

gravity which become a religious man. These

minutia were not always so easy to acquire ; and to

most,

frequently presented some difficulty. The

neophyte was next shown how he should bow, and when

the various kind

of bows were to be made. If the bow was

to be profound, it was pointed out to him how he could tell practically

when it

was correctly made, by allowing his crossed arms to couch his knees.

Then he was instructed how to get into his

bed in order to observe due modesty, and how to rise from it in the

morning, in

the common dormitory. In a word, he was

exercised in all the usual monastic manners and customs.

After these first lessons in the external behaviour of a monk, the novice was taught the necessity and meaning of such regulations as custody of the eyes, silence, and respect for superiors and other brethren, both outward and inward. Step by step he was drilled in the exercises of the regular life, and taught to understand that they were not mere outward formalities, but were or ought to be, signs of the inward change of soul indicated by the monk’s cowl. The cloister was the novice’s schoolroom. His master assigned to him a definite place amongst his fellows, and after the morning Office he sat there in silence with the book given him, out of which he was to learn some one of the many things a novice had to acquire during the year of probation. The Rule : the prayers and psalms he had to ---107--- learn by

heart : the correct method of singing and chanting and reading : and

sometimes

even the rudiments of the Latin language, without a knowledge of which

the work

of a choir brother was impossible, were some of this daily studies ;

and hard

work enough it was to get through it all in twelve fleeting months. His

master, however, was ever at hand to help

him and encourage him to persevere, if he only showed the real signs of

a call

to the higher life.

Before beginning their work the novices always had to recite a De profundis and a prayer, as an exercise in decorum and deliberation. No more than thee of them were to use the same book together. At times there must have been a considerable amount of noise, for in practicing the reading, signing, and chanting they were all directed to make use of the same tone, as they would have to do in the church or refectory. The novice-master began their exercises with them, but he could pass them on for this kind of drilling to someone else, provided he was competent and a staid and true religious. Thrice during the year of probation, if the novice persisted in his design, his master brought him to the morning Chapter, where on his knees he renewed his petition to be received as one of the brethren. At length as the end of the year approached, a more solemn demand was made and, the novice having been dismissed from the Chapter, the master gave his opinion, and the verdict of the convent was taken. If the vote were favourable to the petitioner, a day was appointed for him to make his vows, and having pronounced these with great solemnity, he received the kiss of peace from all as a token of his reception into the full charity of the brotherhood. In ---108--- some

Orders, certainly amongst the Benedictines, the ceremony concluded with

a

formal and ceremonious fastening of the hood of the newly professed

over his

head. This he wore closed for three

days, as a sign of the strict retreat from the world, with which he

began his

new life as a full religious ; and just as our Lord was buried in the

tomb for

part of three days to rise again, so was he buried to the world to rise

again

to a new life. At the morning Mass of

the third day the superior with some ceremony unfastened the hood, and

the late

novice joined the ranks of the junior monks, who for some years after

their

profession still remained under the eye and guidance of an immediate

superior

called the junior master.

To complete the account of the

officers of a monastery some few words are necessary about the

officials, whose

duties lasted merely for the week. The

first of these was known as the hebdomadarian,

or the priest for the week. In most places, apparently, the

hebdomadarian began

his labours with the vespers on Saturday and continued them till the

same time

the following week. It was his chief

duty to commence all the various canonical Hours during his week of

office. He gave all the blessings that

might be required ; he blessed the holy water and, on the proper days,

the

candles and ashes. He gave even the

blessings

bestowed upon the weekly servers on the Sunday morning. Besides these

duties it was his office to

sing the High Mass on all days during the week, and in monasteries

where there

were two public Masses, during the week which followed his week of

service, he

took the early Mass and assisted at the second.

---109--- A second weekly official was

the antiphoner,

whose duty it was to read

the Invitatory at Matins. He did so

alone on ordinary days, and sang it with an assistant, or even with two

or

more, on greater feasts. He gave out, or

intoned, the first Antiphon at the Psalms, the Versicles, the

Responsoria after

the Lessons, and the Benedicamus Domino

at the conclusion of each Hour. He also

read the “Capitulum,” or Little Chapter, and whatever else had to be

read at

the morning Chapter.

Amongst the other weekly officials may be noted the servers and the readers at meals. These brethren could take something to eat and drink before the community came to the refectory, in order the better to be able to do their duty. The reader was charged very strictly always to prepare what he had to read beforehand and to find the places, so as to avoid all likelihood of mistakes. He was to take the directions of the cantor as to pronunciation, pitch of the voice, and at the rate at which he was to read in public. If he were ill, or for any other reason was unable to perform his duty, the cantor had to find a substitute. The servers began their week of duty by asking a blessing in church on Sunday morning. They were at the disposal of the refectorian during their period of service, and followed his directions as to waiting on the brethren at meal times, preparing the tables, and clearing them after all had finished. With the reader, and other officials who could not be present at the conventual meals, they took theirs afterwards in the refectory. ---110--- -end chapter- |

| Historyfish

pages, content, and design copyright (c) Richenda

Fairhurst, 2008 All rights reserved. No commercial permissions are granted. The Historyfish site, as a particular and so unique "expression," is copyright. However, some (most) source material is part of the public domain, and so free of copyright restrictions. Where those sections are not clearly marked, please contact me so I can assist in identifying and separating that material from the Historyfish site as a whole. When using material from this site, please keep author, source, and copyright permissions with this article. Historyfish intends to generate discussion through shared information and does not claim to provide, in any way, formal, legal, or factual advice or information. These pages are opinion only. Opinions shared on historyfish are not necessarily the opinions of historyfish editors, staff, owners or administrators. Always consult proper authorities with questions pertaining to copyrights, property rights, and intellectual property rights. It is my intent to follow copyright law (however impossibly convoluted that may be). Please contact me should any material included here be copyright protected and posted in error. I will remove it from the site. Thank you. |