(go to Abbey Pages Home)

(go to Monastic Pages Home)

(go to Historyfish Home)

Leave a Comment

|

<<Back

to Parts of a Monastery. (go to Abbey Pages Home) (go to Monastic Pages Home) (go to Historyfish Home) Leave a Comment |

|

Cloister and

Living Quarters in a Medieval Monastery

Cloister and

Living Quarters in a Medieval Monastery| The

parts and functions of the Medieval Monastery, using the groundplan for

Beaulieu

Abbey as a basemap. Return to the Parts

of a Monastery page to view the map, room labels, and basic

information about the abbey. Scroll

down for individual explanations of the basic rooms, parts, and

functions of a medieval abbey. For information about the

parts of the abbey church, see Parts of the Church. |

| Living Quarters

(Scroll Down) Monks Frater and Lay Frater (Refectory) The Kitchen The Cellars The Infirmary (and Misericorde) Calefactory (Common Room or Warming House) |

Living Quarters (next page) Monks Dorter and Lay Dorter The Lavatory Parlour The Cloister Chapter House Fish Ponds and Grounds |

|

|

|

Shared meals in

a monastery were as

ritualistic as all other

parts of the religious life. In

monasteries, such as Beaulieu, where there lived Lay Brothers as well

as Ordained Monks, the ritual of mealtime was kept separately, and each

group had their own washing sink and dining hall, though both were

served by the same kitchen. Only one meal was served per day, and for that meal the monks processed from the church through the cloister to the refectory, underwent washing at the lavatory sinks, washing their hands, faces, and knives, and then, when the Kitchener (and cook) announced the meal was ready, they processed into the frater. They sang psalms before and after taking their meal, which was always served with a loaf of bread, this signifying the sharing of bread among Christians. No talking was permitted, every monk instead listened to the Reader who read a scripture from the pulpit in the refectory. Sometimes talking was allowed, but then only very quietly as necessary between the prior or abbot and his guests. Any food left uneaten at the end of the meal was taken into a basket and given to the poor. In addition, one extra meal was always prepared and one poor man chosen to come into the refectory to receive it. |

| |

Image from English Monastic Life F.A.Gasquet, 1904 |

|

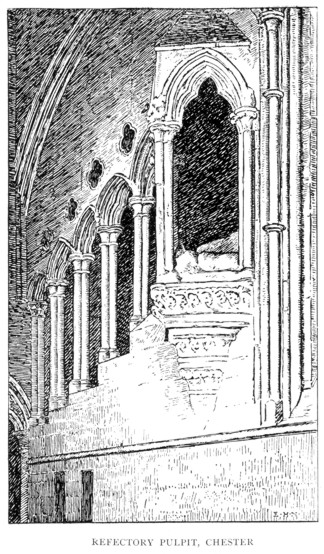

| From English

Monastic Life, by F.A.

Gasquet:

"The refectory, sometimes called the fratry or frater-house, was the common hall for all conventual meals. Its situation in the plan for a monastic establishment was almost always as far removed from the church as possible, that is, it was on the opposite side of the cloister quadrangle and, according to the usual plan, in the southern walk of the cloister. The reason for this arrangement is obvious. It was to secure that the church and its precincts might be kept as free as possible from the annoyance caused by the noise and smells necessarily connected with the preparation and consumption of the meals. "As a rule, the walls of the hall would no doubt have been wainscotted. At one end, probably, great presses would have been placed to receive the plate and linen, with the salt-cellars (salt dispenser), cups and other ordinary requirements of the common meals. The floor of a monastic refectory was spread with hay or rushes, which covering was changed three or four times in a year ; and the tables were ranged in single rows lengthways, with the benches for the monks upon the inside, where they sat with their backs to the paneled walls. At the east end, under some sacred figure, or painting of the crucifix, or of our Lord in glory, called the Majestas, was the mensa major, or high table for the superior. Above this the Scylla or small signal-bell was suspended. This was sounded by the president of the meal as a sign that the community might begin their refection, and for the commencement of each of the new courses. The pulpit, or reading-desk, was, as a rule, placed upon the south side of the hall, and below it was usually placed the table for the novices, presided over by their master. |

||

Image from English Monastic Life F.A.Gasquet, 1904 |

||

|

"Amongst the

other weekly officials may be noted the servers

and the readers at meals. These brethren could take something to

eat and

drink before the community came to the refectory, in order the better

to be

able to do their duty. The reader was charged very strictly

always to

prepare what he had to read beforehand and to find the places, so as to

avoid

all likelihood of mistakes. He was to take the directions of the

cantor (liturgist)

as to pronunciation, pitch of the voice, and at the rate at which he

was to

read in public. If he were ill, or for any other reason was

unable to

perform his duty, the cantor had to find a substitute. "The servers

began

their week of duty by asking a blessing in church on Sunday

morning. They were at the disposal of the refectorian during

their period

of service, and followed his directions as to waiting on the brethren

at meal

times, preparing the tables, and clearing them after all had

finished." |

||

|

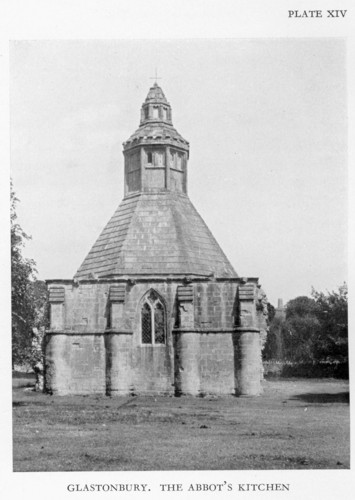

The monastic kitchens were

overseen

by the

Much ritual surrounded the serving of food, what type must be served, and in what amounts. In some institutions, servings were carefully measured on plates beforehand, and in others, communal plates were placed on the table and eaten in a manner similar to that of the manor house, from shared plates. The work of the kitchen tended to be segregated according to what needed to be prepared and the quantity of food needed. In a larger monastery, the main kitchen would be used primarily for making pottage, sauces, custards, and roasting meats. Bread and pastry (such as for pies) would be baked in a separate kitchen, with the bread of the communion baked in a sacred space set aside for that purpose, perhaps in the kitchens, but perhaps also in an area of the church itself. |

||

Image from The Home of the Monk,

by Rev. D.H.S. Cranage, 1926 |

||

| Yet another

kitchen would serve the

monastery servants and guests those who had come on pilgrimage or

seeking

charity (alms) or rest (such as the infirm, should the monastery

include a

hospital). This kitchen would be

located on the grounds, but not within the gates of the cloister. Important guests would be served from

the

monastery kitchen itself, and infirm monks who lived within the

cloister might also have a separate kitchen to serve them. Butchering and

cleaning of animals would be done away from the monastery gates. Beverages were not the domain of the kitchen, but instead were prepared and stored in the buttery. (Many beer concoctions included things like milk, eggs, sugar, spices and butter. A raw egg in warmed beer was common. Yum.) Some monasteries also had a brewhouse for brewing ale or beer, or cellars for fermenting wine, or even distilleries for making the quintessential spirits. Though it was not only liqueur which was distilled. Monks experimented with the distillation of many things, including chickens. |

||

|

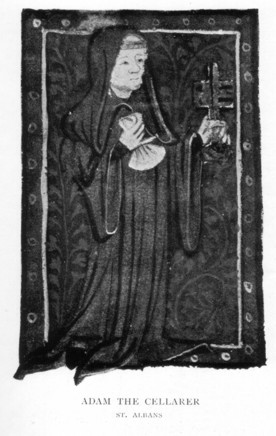

The cellars were the storeroom of the

monastery, and was used

for storing most everything used to upkeep the house, from salt for

preserving meat and for the table salt cellars, to

beeswax for

the altar candles. The Cellarer was the

official in charge of procuring almost all that was needed to run the

‘household’ of the monastery smoothly. His charge

extended to the manors and farmland of the monastery, the tithe barns,

and other duties of storage and procurement. The duties of the

Cellarer, according to F.A.

Gasquet in English Monastic

Life, were: "Besides

the main part of this office as caterer to the community, on the

cellarer

devolved many other duties. In fact, the

general management of the establishment, except what was specially

assigned to

other officials, or given to any individual by the superior, was in his

hands. In this way besides the question

of food and drink, the cellarer had to see to fuel, the carriage of

goods, the

general repairs of the house, and the purchases of all materials, such

as wood,

iron, glass, nails, etc. |

||

Image from English Monastic Life

F.A.Gasquet, 1904 |

||

|

"Some

of the Obedientiary accounts (Officer's accounts) which have survived

show the multitude and

variety

of the cellarer’s cares. At one time, on

one such Roll, beyond the ordinary expenses there is noted the purchase

of

three hundred and eighty quarters of coal for the kitchen, the carriage

of one

hundredweight of wax from London, the process of making torches and

candles,

the purchase of cotton for the wicks, the employment of women to make

oatmeal,

the purchase of “blanket-cloth” for jelly strainers, and the employment

of “the

pudding wife” on great feast days to make the pastry.

He had, of course, frequently to visit the

granges and manors under his care, to look that the overseer knew his

business

and did not neglect it, to see that the servants and labourers did not

misconduct themselves, and that the shepherds spent the nights watching

with

their flocks, and did not wander off to any neighbouring tavern. Besides this he was charged to see that the

granary doors were sound and the locks in good order, and in the time

of

threshing out the corn he was to keep watch

over the men engaged in the work and the women who

were winnowing."

|

||

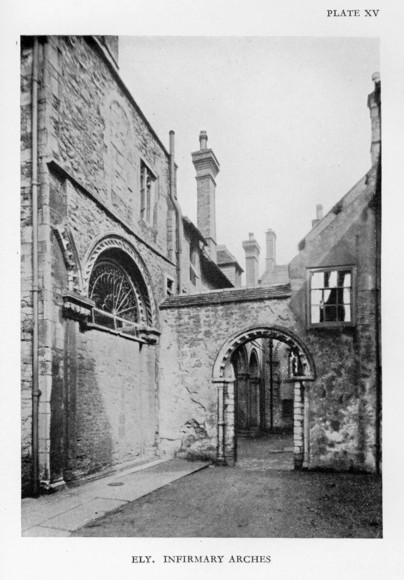

The Infirmary The infirmary at any monastery served as a place to care for the sick, the elderly, and those who needed rest. Medicines and special foods were provided, but much more importantly, the infirmary served as a place where the seriously ill monk or nun would receive assistance in preparing their soul for death. Care of the infirm and sick was considered of the highest moral importance, and, in Christ’s example of His own care of the weak and sick, the abbot himself was instructed to visit the ailing every day to comfort and encourage them, as well as to make sure that their needs were being properly met. (Monasteries also often founded and supported hospitals near to the monastery--but not within the cloister--for permanently disabled, or elderly poor men and/or women. These hospitals could also serve as places of temporary rest. Christians of the time believed in Christ's exhortation to his followers that care of the sick constituted a primary moral obligation: ‘Truly I tell you, just as you did it to one of the least of these my brothers, you did it to me." Matthew 25:40.) |

||

Image from English Monastic Life F.A.Gasquet, 1904 |

||

|

Additionally, the infirmary was

a place to

support recuperation

and relaxation. Under the guidance of

the Infirmarian, the duties and responsibilities of the communal life

could be

relaxed a little. Those suffering from a ‘weariness’ brought on

by

the strictures of the Rule and the observance

of the Hours could find calm and return to their duties with renewed

devotion. Some think that this is why the

tradition of

regular bleeding endured in monasteries, because the four days rest it

offered

were welcomed.

For those who

required an

emotional rest (perhaps suffering

from depression, or other form of emotional or intellectual fatigue) or

for

those who were to rest after being blooded (see CALEFACTORY), while

they were

under the care of the infirmarian, they usually did not stay in the

infirmary. The remedy for both emotional

weariness and ritual bleeding was quiet rest, opportunity for

reflection, and,

in the case of the weary, walks in the open air. As

such, these patients remained in the

dorter, or dormitory. Their duties, however, were

eased, and repose in the Chapter House, Calefactory or dorter was

encouraged. Those who had been blooded took their meals in the

misericorde, which was the infirmary frater (or dining room). |

||

Image from

The Home of the Monk, by Rev. D.H.S. Cranage, 1926 |

||

| The infirmary also served as a retirement community for monks who were no longer able to keep up their duties to the house because they had slipped into weakness, senility, or dementia (and so could not keep silent). Though the elderly monks were still required to keep the rule as they were able, things were easier and primary importance was placed on their spiritual needs and bodily comfort. As such, the Infirmary could become a community within a community. It had its own frater (dining room) called the misericorde, an attached chapel for celebrating Mass and reciting the Hours, and was supplied by its own kitchens (sometimes called a meat kitchen), which produced easily digestible foods (such as bread soaked in mare's milk), and foods to strengthen those who had been blooded. | ||

| The Calefactory, also called the Warming House or Common Room, was a place for the monks to relax together, and, in winter, enjoy the benefit of a hot fire, especially after night offices. Monks had specially issued ‘night boots’ and robes so that they could be as warm as possible, but the churches were large and unheated and often drafty. After the night and early morning offices, they were allowed time to congregate together by the fire and warm up. Monks also

practiced ritual bleeding where two to six monks

at a time (depending on the size of the house) were bled by the

Infirmarian, or

someone qualified to perform the procedure. Being

blooded was considered a health regimen, and it was

thought to

purge the body of impurities. (Perhaps in

the days when heavy metals (such as lead and mercury) were used in

plate

glazing and water pipes, periodic bleeding helped purge the body of

this metal

buildup? It seems there must have been some type of benefit,

either known or unknown, to the procedure.) Each monk was blooded once a year, or occasionally twice, on a rotating basis. Strict rules followed all aspects of the ritual. The operation took place during the afternoon in the Calefactory (common room or warming house) by a warm fire with a styptic and a basin. After, the monk’s arm was wrapped tightly in bandages and for four days he was excused any activity that would risk a resumption of the bleeding, such as too much standing or kneeling, or any activity where the bandages might be accidentally brushed or bumped. The monk was excused choir duties (though he was still expected to attend the offices) and, though he still had to wake up during the night for prayer, he could go to the infirmary chapel instead of the church, where the service was quicker and simpler. An easier schedule in general was allowed, rest encouraged, and foods such as an extra egg and beef broth, were given to help build strength. |

||

To Living Quarters in the Monastery, page two>> <back to top> |

| Historyfish

pages, content, and design copyright (c) Richenda

Fairhurst, 2008 All rights reserved. No commercial permissions are granted. The Historyfish site, as a particular and so unique "expression," is copyright. However, some (most) source material is part of the public domain, and so free of copyright restrictions. Where those sections are not clearly marked, please contact me so I can assist in identifying and separating that material from the Historyfish site as a whole. When using material from this site, please keep author, source, and copyright permissions with this article. Historyfish intends to generate discussion through shared information and does not claim to provide, in any way, formal, legal, or factual advice or information. These pages are opinion only. Opinions shared on historyfish are not necessarily the opinions of historyfish editors, staff, owners or administrators. Always consult proper authorities with questions pertaining to copyrights, property rights, and intellectual property rights. It is my intent to follow copyright law (however impossibly convoluted that may be). Please contact me should any material included here be copyright protected and posted in error. I will remove it from the site. Thank you.  |