(go to Abbey Pages Home)

(go to Monastic Pages Home)

(go to Historyfish Home)

Leave a Comment

| |

|

<<Back

to Parts of a Monastery. (go to Abbey Pages Home) (go to Monastic Pages Home) (go to Historyfish Home) Leave a Comment |

|

Cloister and

Living Quarters in a Medieval Monastery

Cloister and

Living Quarters in a Medieval Monastery| The

parts and functions of the Medieval Monastery, using the groundplan for

Beaulieu

Abbey as a basemap. Return to the Parts

of a Monastery page to view the map, room labels, and basic

information about the abbey. Scroll

down for individual explanations of the basic rooms, parts, and

functions of a medieval abbey. For information about the

parts of the abbey church, see Parts of the Church. |

| Living Quarters

(previous page) Monks Frater and Lay Frater (Refectory) The Kitchen The Cellars The Infirmary (and Misericorde) Calefactory (Common Room or Warming House) |

Living Quarters

(Scroll Down) Monks Dorter and Lay Dorter The Lavatory Parlour The Cloister Chapter House Fish Ponds and Grounds |

|

|

|

The Dorter is

also called the Dormitory, and it is where the

monks slept. At first, all the monks

slept together (on the cave floor, if the group gathered around a

hermitage

such as that at Knaresborough or those in As the monastic

Orders developed, and the centuries passed,

sleeping arrangements changed. The

communal hall became divided by screens, and then into separate

cubicles along

the dormitory hall. Gasquet explains “Every monk had a little chamber to

himself. Each chamber had a window towards the Chapter, and the

partition

betwixt every chamber was close wainscotted, and in each window was a

desk to

support their books.” Also, the lavatory (or rere-dorter)

was usually close by the dorter and easily accessible. Come the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, the abbots and priors of larger religious houses found an increasing need to act as hosts for important guests. To preserve the tranquility of the dormitory, the abbot or prior constructed separate accommodations, some quite sumptuous, that allowed him to entertain guests to the monastery in the style the gentility were accustomed too, without disrupting the austerity of monastic life for the others in the cloister. |

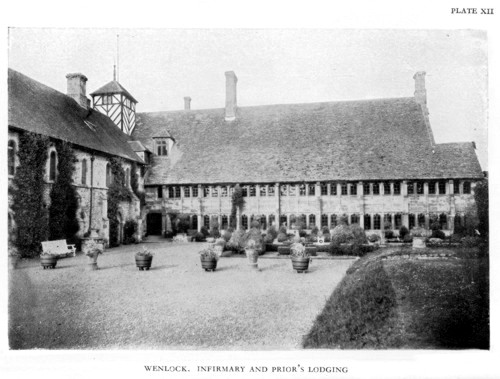

Wenlock Priory. Infirmary (below) with Prior's rooms (above). Image from Home of the Monk by Rev. D. H. S. Cranage. |

||

|

The monastics rose from their beds at the sound of a bell, and in some instances prayed right there at the bedside. Traditionally, however, they processed down the night stair (a back way, and all indoors, from the cloister to the church) where they took up their places in the choir and began their nightly worship. Because churches were cold at night, special warm night clothing and warm, felted wool “night boots” were worn.

|

||

|

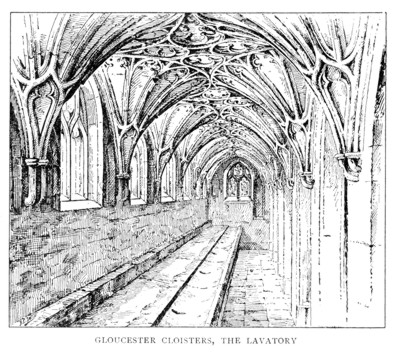

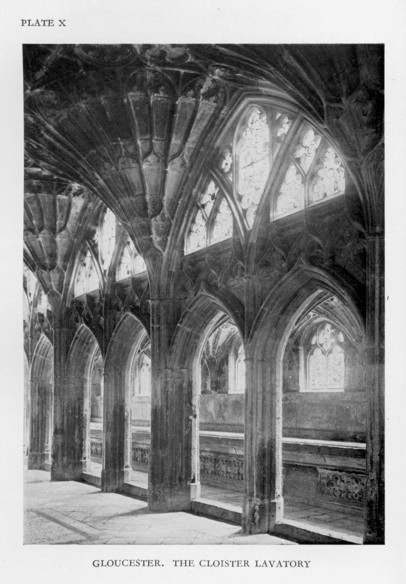

Ritual surrounded

every aspect of the monastic life,

including grooming. As a group of

educated men and women, monastics understood the need for sanitation

and

cleanliness well before science ‘discovered’ bacteria as a primary

source of

contagion. Smell was long understood to

carry contagion, and even the generals of ancient

Personal cleanliness in a monastery included the everyday washing before meals and other ceremonial or official activities, Saturday foot washing, barbering (hair tonsuring and shaving), tub bathing (four times a year), and toileting. Washing before the communal meal was done right outside the dining room (called the frater or refectory) where a sink flowing with water (heated in winter) also included clean sand where the monks could wash their knives (the primary eating utensil of the middle ages) before heading in to their meal. A cupboard (aumbry) near the sink held clean linen towels. |

||

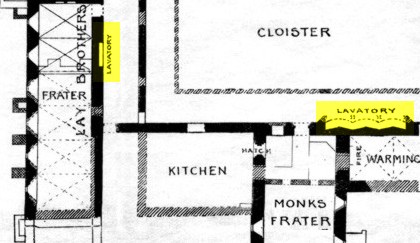

Image from English Monastic Life F.A.Gasquet, 1904 |

||

| In

Beaulieu Abbey, which had separate facilities for lay

monks and professed monks, each frater was equipped with its own sink

and towel

cupboard. There was also a sink (laver)

near the presbytery, where clergy could perform ritual ablutions

(washing)

before |

||

Image from English Monastic Life F.A.Gasquet, 1904 |

||

| Toileting

was done in the

rere-dorter, a room near the monks'

dorter that was easily accessible during the night.

Toilets were holes in a long plank along which the monks

sat. Waste ran down through pipes or channels into running

water and was swept away. Warm water

was

supplied during the winter for washing and clean towels as well. Bathing used this similar system of waste

water drawn away, the bathing tubs lined with fresh clean hay and the

monks supplied

with soap, herbs, towels, and warm water. |

||

Image from The Home of the Monk by Rev. D. H. S. Cranage |

||

| The final ‘health’ ritual was that of bloodletting. (For more about this, see INFIRMARY.) | ||

The Parlour |

||

|

The parlour was a room within

the cloister where members of the monastic community could visit with

each other during times of respite, could convalese after being bled

(see infirmary) and after illness, and, most importantly, the place

where the rule of silence could be eased so that monks and nuns could

visit with members of their families.

In addition, families of monks and nuns often provided financial support to the monastery through donations of money, goods, and other forms of patronage. In the case of nuns, a 'dowry' was paid by the family to the monastery so that she might be admitted to the convent. This dowry helped support her for her lifetime at the monastery. In addition to the dowry, relatives of nuns could provide clothing, bring small gifts (even such as parrots, dogs, or marmosets for the nun to keep as a pet) and bring food, also. These things not only helped offset the maintainance cost for each nun, but they were a reminder of social status, as many nuns came from wealthy and influencial local families. (These kinds of gifts are also what bishops most complain about during visitations to women's convents.) As the financial health of some women's establishments declined in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, gifts or food and warm clothing became even more important, and, indeed, essential. The other primary visitor to the parlor would have been the parents of the girls who were enrolled in women's covents for their schooling. It was very common for parents with some extra money to send their daughters to convents to be educated. Lessons would include embroidery, weaving, and sewing, religious education, and (though not always) reading. Primary languages, depending on the era, were Latin, Greek, French and later, English. Dance was a vital component to

the medievel education, and later boy's schools devoted four or more

hours each day to its study. And, as boys didn't grow up to dance

with each other, I imagine girls received similar instuction.

Though I can't imagine nuns teaching this subject, it must also have

been taught at some point, either at the convent, or at home.

|

||

|

Latin, claustrum,

or

‘enclosed place.’ A square or

rectangular central courtyard, usually built on the south side of the

church, surrounded

on all sides by the inner (claustral) rooms of the monastery, such as

the

Chapter Room and monastic kitchens.

|

||

[Bavon Abbey, ruins.] |

||

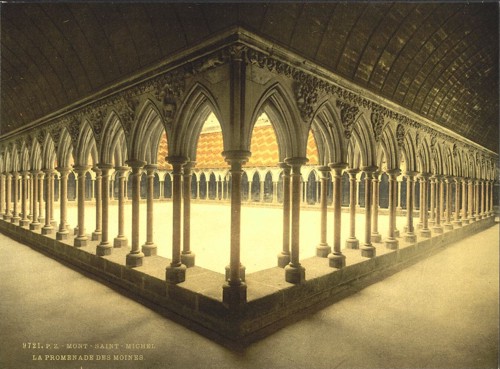

| The large center of the cloister was open to the elements, and often included a well and herb gardens planted with medicinal, and other plants useful to the monastery (such as sweet woodruff which could be mixed with rushes for strewing the floors of the church, dormitory, and choir). The center open square of the cloister, called the cloister garth, was surrounded by a covered, often colonnaded, walkway on all four sides, this walkway called the alley. Whether the alley was open to the outdoors or not depended on the style and location of the monastery, with weather an obvious consideration. Monasteries in cold climates built a sheltering alley, either sealing it behind unglazed windows or using protective wooden shutters. The alley, or walkway, was also referred to as the ‘Promenade’ as it was along this walkway that the monks would sing and walk in procession. | ||

[Monks Promenade, Mont Saint Michel, France. Detroit Publishing, photochrom, 1905.] |

||

| A second story above the cloister often overhung the alley to form the roof and overlook the inner courtyard. The upstairs spaces were protected workspaces for the monks, and protected with glass and shuttering from the cold and damp. The northern side within the cloister particularly, which received the best natural light, was the primary location for books and carrels (desks and workspaces), though there could be carrels along the east and west sides as well. | ||

[Convent of San Martino, with burying ground, Naples, Italy. Detroit Publishing, Photochrom, 1905.] |

||

|

|

||

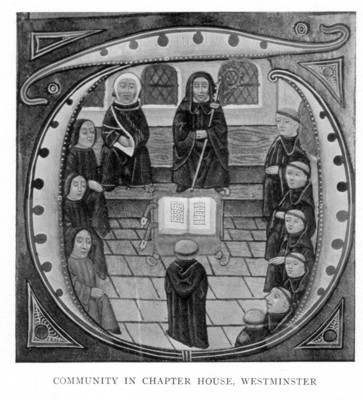

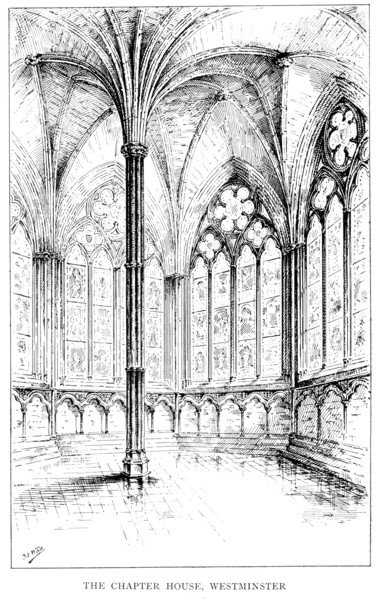

The chapter house was the

central

meeting place of the members of the monastic community, either monks or

nuns,

and the place where the official business of the monastery was

conducted, both

spiritual and secular. The Chapter

meetings served the functions of keeping the governance of the

monastery in

check, allowing all true members to participate and have their chance

to speak

and participate, and reinforcing the communal living and discipline

standards

of the Order.

|

||

Image from English Monastic Life F.A.Gasquet, 1904 |

||

| Chapter Meetings included a short devotion, the confession of sin, and the meting out of punishment, which, if it were corporal, was administered during the meeting itself. Key monastic officials, presided over by the abbot, carried out the monastery business, but in front of the brethren so all would be included in the process overall. Signing official orders and documents was a shared responsibility, with the seal of the monastery kept in a chest belonging to the community, to be opened and used only in chapter. (Individual monastic establishments, of course, might differ.) | ||

Images from

English Monastic Life F.A.Gasquet, 1904 |

||

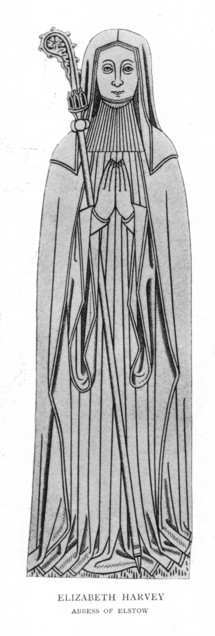

| The size of the monastery, the Order and Rule of the monastery, and the wealth of the establishment, could make considerable differences to both the manner of Chapter Meetings and the grandeur of the Chapter House. In large, wealthy abbeys, the Chapter Room could be quite large, round in shape, or polygonal for better acoustics. The monks would enter from the cloister walkway, and the door, called a Vestibule, could be extraordinarily elaborate and ornately carved. Wealthy abbeys were run by wealthy, often titled, abbots and they often ran extensive businesses. Some abbeys even built castles to protect their shipping and commerce interests. | ||

[Vestibule of the cathedral, Dalmatia. Detroit Publishing, photochrom, 1905.] |

||

| Other abbeys (though these could still be very wealthy) focused on austere living, or were smaller priories and so lacked the resources of the larger abbeys. The Chapter House in this instance would be plain and rectangular and perhaps be fitted with benches along the wall for seating. The focus in this case was less on running extensive commercial enterprise and more on the devotional life of the brethren or sisters. | ||

Image from English Monastic Life F.A.Gasquet, 1904 |

||

| Fish

Ponds and Grounds Monasteries were

self-sustaining communities. Included in the monastic "grounds"

were not only the church and cloister, but surrounding farms, rows of

market shops, manor homes (and their farming fields), village churches,

many hospitals, whole villages (including leper colonies), and even

castles. Large powerful abbeys were financial powerhouses and

that included, sometimes, extensive trade that would be protected by

garrisons of men-at-arms, and, the building of castles.

Castles were not the norm, however. The basic English monastery included the monastery grounds, a manor or two, extensive farming fields, a communal kitchen and bakery and gristmill (for grinding barley and wheat and making bread), and, a village. A monastery, then, ran similarly to any other feudal enterprise, a 'lord' at the top with 'surfs' and bond servants at the bottom. To be fair, however, communities headed by monastics fared far better than the average community under a secular 'lord.' Many stories tell of miracles performed by abbots to feed their communities during famine, and the lengths they went to provide hospital and other kinds of care to widows, orphans, and the infirm. The average monastery estate would have fish ponds stocked with fish, tithe barns which held the monastery's share of the grain raised on the estate, retting ponds for linen, tanning sheds, everything needed for self-sufficiency on a normal estate. Manors owned by the monastery were often run by monastic officials who sometimes also lived in them. These manor-farms could be adjacent to the monastery itself or some distance away. Wool was a vital part of the English economy in many places. All the sheep of the village shared the monastic pasture ranges, just as all the pigs ate from the mast of the forest floor. But the monastery not only had their own pigs and sheep, but took a tithe or rent portion also from those who lived on their estates or under their purview. Village churches could also be

purchased and owned by monastic institutions. Often, local

churches were owned by secular lords and ladies, so it make sense that

monasteries could own them also. In a nutshell, then, all the

things required to run a medieval estate and community, and all the

basic systems of feudalism, could be found also in the monastic system.

|

||

| To Living Quarters in the Monastery, page one>>>> <back to top> |

| Historyfish

pages, content, and design copyright (c) Richenda

Fairhurst, 2008 All rights reserved. No commercial permissions are granted. The Historyfish site, as a particular and so unique "expression," is copyright. However, some (most) source material is part of the public domain, and so free of copyright restrictions. Where those sections are not clearly marked, please contact me so I can assist in identifying and separating that material from the Historyfish site as a whole. When using material from this site, please keep author, source, and copyright permissions with this article. Historyfish intends to generate discussion through shared information and does not claim to provide, in any way, formal, legal, or factual advice or information. These pages are opinion only. Opinions shared on historyfish are not necessarily the opinions of historyfish editors, staff, owners or administrators. Always consult proper authorities with questions pertaining to copyrights, property rights, and intellectual property rights. It is my intent to follow copyright law (however impossibly convoluted that may be). Please contact me should any material included here be copyright protected and posted in error. I will remove it from the site. Thank you.  |