(go to Abbey Pages Home)

(go to Monastic Pages Home)

(go to Historyfish Home)

Leave a Comment

|

<<Back

to Parts of a Monastery. (go to Abbey Pages Home) (go to Monastic Pages Home) (go to Historyfish Home) Leave a Comment |

|

Parts

of the Church (page one)

Parts

of the Church (page one)| The

parts and functions of the Medieval Monastery, using the groundplan for

Beaulieu

Abbey as a basemap. Return to the Parts

of a Monastery page to view the map, room labels, and basic

information about the abbey. Parts of the church, below.

Information about the monastery living

quarters, here. |

| Page One (scroll down)

The Presbytery (Chancel) The Nave The Quire (Choir) Anchorhold or Anchorage |

Page Two

(next page) Chapels, Shrines, and Chantries. Transcepts Vestry Churchyard (Graveyard) |

|

|

|

The Presbytery (or Chancel) A

‘Presbyter’ was a religious

elder, and the Presbytery was named for the location within the church

where

these elders (the clergy, or those of highest rank or importance) would

sit. The presbytery could be raised

higher than the nave, with the high altar at the easternmost point,

perhaps raised

higher still.

Earliest altars were simply tables, or the tombs of martyred saints. As churches grew and the clergy regulated worship, the altar was set apart and placed within the most sacred part of the church, decorated over with canopies and curtains, and access to it was limited. Stone remained, however, the primary material used in building the high altar, and often the precious relics or bones of a particularly powerful saint might be interred within it. In this way they resembled the shrines, or tabletombs of the Roman and Byzantine burials. |

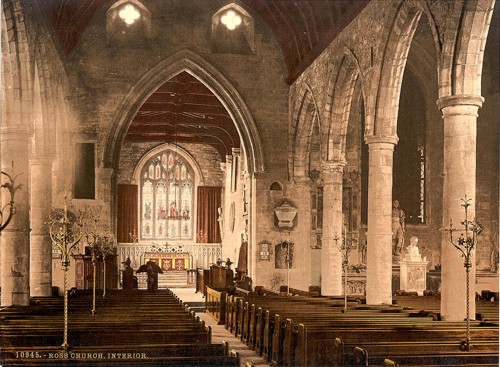

[Church, interior, Ross-on-Wye, England] |

||

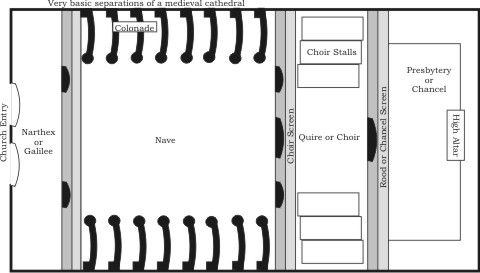

| As the place where the most sacred of the church mysteries took place, the presbytery was the holiest part of the church. After the 12th century, the presbytery was separated from the choir below by a screen, called a rood (featuring the crucifix) or chancel screen. The choir was further separated from the nave by a choir screen, so a member of the congregation looking up toward the pulpit (lectern) would see two screens, behind which the most sacred parts of the Mass were carried out, the chanted liturgical song of the monastery choir, and behind them, the celebration of the Eucharist. | ||

[Hereford Cathedral] |

||

|

Surrounding

the presbytery/chancel were smaller chapels (see chapels) or shines to

the patron or important saints of

the abbey or community, as well as to benefactors of the abbey itself.

On the eastern wall was usually a chapel dedicated to the Virgin

Mary.

The Virgin was a primary figure to all Christians of the time, and many

monasteries, hospitals and universities, and almost all Cistercian

foundations, were dedicated to her.

|

||

|

||

| To the south side of the presbytery was the Priest’s Door where the priest could enter and begin services. The door led directly into the presbytery/chancel from either the churchyard, vestry, or cloister. | ||

|

Early

Christian churches emphasized the importance of the communal gathering

and there were few

screens, canopies, or curtains separating worshippers

from another, or clergy from the congregation, or the congregation from

the 'mysteries.' Walls and screens came in slowly, starting with

a wall beween the choir and the congregation. By the latter

middle ages, the great monastic

churches and cathedrals had separated the belly of the church into

distinct

sections, with walls or screens at the narthex, choir, and presbytery

(chancel). The goal at the time was to place primary importance

on the most sacred part of the church, that of the high altar, where

priests celebrated the Mass and Eucharist.

|

||

|

||

| The Nave today is usually the largest part of the church, the place where the general congregation assembles for worship. In the middle ages, however, it was not necessarily largest and could be quite small. Additionally, the medieval nave did not include benches or chairs for seating, those came later. Early congregations stood, or, like Shakespeare's groundlings, they simply sat down on the floor. The only seating provided were stone benches built into the church walls and there the elderly, sick, or disabled could rest. | ||

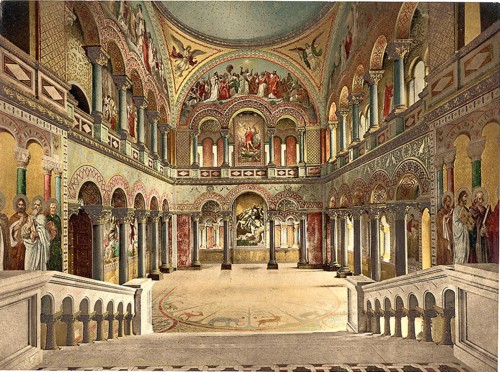

[Interior of St. John and St. Paul's, Venice, Italy] |

||

| Churches of

the

middle ages were

laid out in the form of the cross, with the top of that cross being

the

easternmost point. The parts of the church grew progressively more

sacred the

more easterly they were, so that while lowly penitents might enter the

Narthex

or In some ways the configuration of the medieval churches imitated that of the 'great halls' built by the Kings of the West. In his palace or citadel, the medieval king would sit atop a throne on a raised dais at the top of an ornate and open hall. No one else in the hall would be allowed to sit, though they might lie prostrate on the floor. The great halls provided a physical demonstration of a king's power and position, and were often decorated with religious symbols. Only the chosen few, close aides, esteemed allies or officers, were allowed access to him and the dais. All other petitioners must keep their place or grovel at the door. |

||

[Throne room, Neuschwanstein Castle, Upper Bavaria, Germany] |

||

|

While the ideals

of the church

communities differed from those of governing kings, some of the

trappings that

denoted power were similar for the church as for the hall.

Most particularly the use of penitential

entries, halls (naves), raised dais as inner sanctum (high altar), and

thrones. Like a king, the Abbot or Bishop,

as the tititular head

of that church, diocese, or see, would sit at the top, eastern part of

the

church in large, ornate thrones during the Divine Offices,

feasts and

during

The Nave itself (or Navis, the Latin word for ship), was the central area of the church and in general use by the congregation. The area of the Nave included all the lateral space after the Narthex to the Choir Screen, including to the north and south of any supporting (or decorative) columns, arches or other architecture. Church activities in this space included guild plays (religious in nature) and fundraisers, just as today. In the middle ages, fund raising included a occasion to celebrate, such as a wedding or successful lambing season, and the distribution of plenty of good ale. |

||

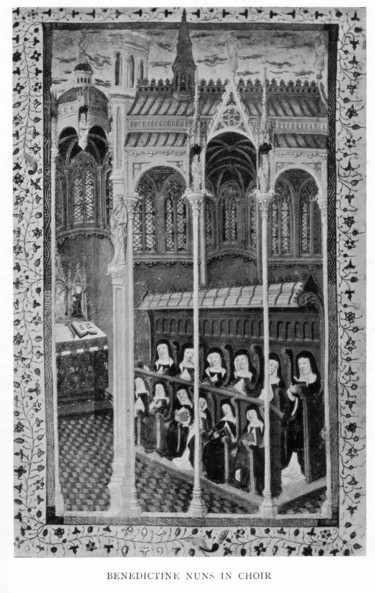

The medieval choir, as today,

was the group

of people who participated by singing as a group

during church services. In the monastery,

however, every monk or nun

was a member of the choir, and expected to always be present and ready

to

participate in the Divine Office. The

few exceptions for non-attendance were for those who were infirm, or

whose

other duties to the monastic house required them to perform other

important functions,

such as preparation of meals or the duty of performing private Masses

for the ailing, or for an important

guest.

|

||

|

||

| The

monastic choir sang in what we

know as Gregorian Chant, also called Plaintchant, or plainsong. The single melodies of the monastic chants

were different for each monastery, and were learned primarily by heart

(with often

strict punishment for those who might not learn quickly or well

enough). There were single voices, but primarily, all

sung/chanted in unison. The religious,

liturgical song was a sacred and

important task of

the religious nun or monk and as such, great care was taken to make

sure the

singing was done well and without mistakes. Harmonized

singing became part of church services in the

15th

century, but when it did, monasteries and cathedrals were often in

competition

with each other to produce the most beautiful music and feature the

most

ethereal and powerful singers. |

||

[Minster, choir east, York, England] |

||

| The part of

the monastic church

building known as the Quire or Choir was separated from the nave with a

sturdy

wall, called the pupitulum, or screen. This Choir Screen helped protect the monks and

nuns from cold and damp, as they performed the offices and hours of the

church

at all hours of the day, and in every kind of weather.

The area where the choir sat was built with

choir stalls, screened and sectioned, some with benches where each

member could

sit or

kneel or stand. If there were books

available to help with services, there were also candles provided for

lighting. Juniors were charged with lighting those

candles and keeping them lit. (Though a single candle or

lamp

in the

freezing dark of a |

||

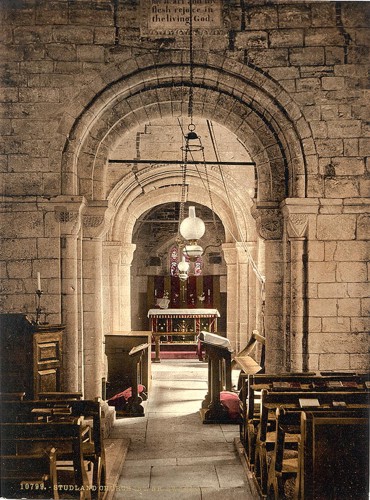

[Studland Church, interior, Swanage, England] |

||

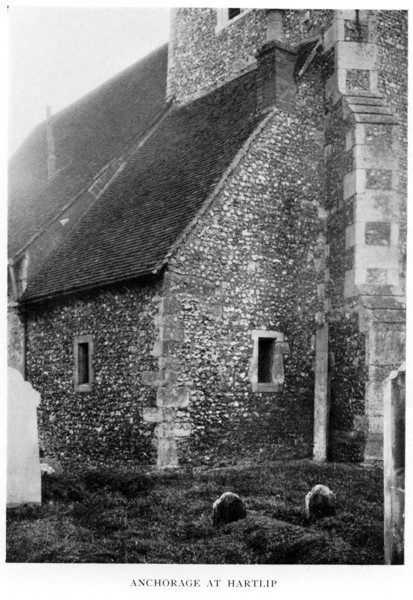

The Anchorhold A number of monastic and other

churches included an anchorhold or anchorage built within, or onto the

side of, the church. These small spaces, of a single or a few

small rooms, held a religious person called a 'recluse' or 'solitary'

and it was their calling to spend their days removed from the company

of others in order that they might give the whole of themselves to the

worship of God. These men and women were held in high esteem by the

church and community, and could receive important visitors who would

ask them for their advice.

The anchorite served as a kind of prophet, making predictions about the future or interpreting the will of God, and offering prayers for those in need of them. Anchorites, also called Anchoresses, were enclosed in their cell sometimes completely with no way of getting out, or at other times attended by one or more servants who could go in and out as they needed. Sometimes, even the anchorite him or herself might go out of the cell. |

||

[Anchorage at Hartlip. From The Hermits and Anchorites of England by Rotha Mary Clay] |

||

|

Similarly to the anchorage or

anchorhold, the properties of a monastery might well include a

hermitage or hermit chapel. A hermit was a solitary, leading a

life of solitude and simplicity like an anchorite. Hermits,

however, were almost always men (especially after the church instituted

authority over them) and were not confined to their cell. A hermit was

often a monk-priest who would celebrate Mass in his little hermit

chapel.

For more information on anchorites and the anchorhold/anchorage, see my short article, What are Anchorites? For more information about hermits, hermitages and hermitage chapels, see The Hermits and Anchorites of England, transcribed here. |

||

To Parts of the Abbey Church, page two>> <back to top> |

| Historyfish

pages, content, and design copyright (c) Richenda

Fairhurst, 2008-2009 All rights reserved. No commercial permissions are granted. The Historyfish site, as a particular and so unique "expression," is copyright. However, some (most) source material is part of the public domain, and so free of copyright restrictions. Where those sections are not clearly marked, please contact me so I can assist in identifying and separating that material from the Historyfish site as a whole. When using material from this site, please keep author, source, and copyright permissions with this article. Historyfish intends to generate discussion through shared information and does not claim to provide, in any way, formal, legal, or factual advice or information. These pages are opinion only. Opinions shared on historyfish are not necessarily the opinions of historyfish editors, staff, owners or administrators. Always consult proper authorities with questions pertaining to copyrights, property rights, and intellectual property rights. It is my intent to follow copyright law (however impossibly convoluted that may be). Please contact me should any material included here be copyright protected and posted in error. I will remove it from the site. Thank you.  |