(go to Abbey Pages Home)

(go to Monastic Pages Home)

(go to Historyfish Home)

Leave a Comment

|

<<Back

to Parts of a Monastery. (go to Abbey Pages Home) (go to Monastic Pages Home) (go to Historyfish Home) Leave a Comment |

|

Parts

of the Church (page two)

Parts

of the Church (page two)| The

parts and functions of the Medieval Monastery, using the groundplan for

Beaulieu

Abbey as a basemap. Return to the Parts

of a Monastery page to view the map, room labels, and basic

information about the abbey. Parts of the church, below.

Link for information about the monastery living

quarters. |

| Page One (previous

page) The Presbytery (Chancel) The Nave The Quire (Choir) Anchorhold or Anchorage |

Page Two

(scroll down) Chapels, Shrines, and Chantries. North and South Transcepts Vestry Churchyard (Graveyard) |

|

|

|

Chapels were places of worship

and

could be as large as a country church or as small as a niche in a wall. In some places, chapels were small

church-like rooms or buildings built into castles and gates, or built

on

estate

properties and owned by the church, a secular family, or an

institution. Guilds might build chapels

into their meeting

halls or a city into its entry-gate. These

chapels might be

owned outright by the family, but were always sanctioned and supervised

under

the local bishopric and subordinate to the local churches and

cathedrals. In monasteries, small

niche chapels lined the church walls along the nave, the transepts, and

even in

the presbytery.

|

[Castle Ruins, the chapel, Goodrich, England. Detroit Publishing, 1905.] |

||

| Chapels

were dedicated to particular saints and sometimes important persons, as

with

memorial chapels where the visitor was encouraged to pray for the

benefactor’s

soul. Niche chapels in monastic churches

might contain a relic of the saint (such as a thread from an apostle’s

cloak or

a martyr's finger bone), or might have painted depictions of the saint

or the

symbols associated with that saint, such as the pig and Larger chapels might include space for many pilgrims to enter or pray at once, and also contain one or more large shrines. |

||

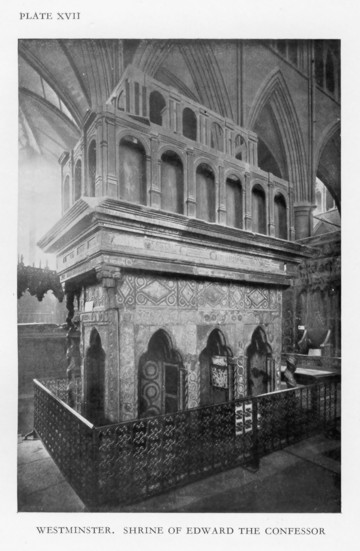

Image from The Home of the Monk by Rev. D. H. S. Cranage |

||

| These shrines showcased important relics, often of the saint to whom the chapel was dedicated. The entry might include the admonition that penitents must remove their shoes before entering or maintain silence within. The pilgrim or visitor was encouraged pray at these chapels, and to make offerings and requests to the saints to whom the chapels were dedicated. | ||

[Chapel shrine with altar in Jerusalem. Photochrom collection, Detroit Publishing, 1905.] |

||

|

Saints,

chapels, and shrines could

all be associated with the workings of miracles. The

monks, in fact, would encourage this by

enthusiastically copying and distributing the stories of saints and the

miracles associated with those of their relics owned by the monastery.

Relics, and

the

miracles associated with them, were an extraordinarily important

component of

the medieval monastic church. Relics

attracted

pilgrims (and their jewels, cameos, and coins), and the patronage of

the wealthy. A monastery with valuable

relics would be

esteemed by association, and it was not uncommon for there to be

squabbles over

ownership of reliquaries, or even outright theft between

institutions.

|

||

[Zara, sarcophagus of San Simeone, Dalmatia, Austro-Hungary. Detroit Publishing, 1905.] |

||

| Chapels

were similar to chantries

in appearance, and both might be built into a church niche, on the

church

grounds, or into the church itself. But

chapels and chantries had very different functions.

Chapels were associated with particular saints

and were a place the general population could go (or, if it were a

private

chapel, a particular group or family) to offer prayers and make

requests of that

saint for health, safety, and happiness. Chantries

were associated with particular people or

families, and built

with the particular intent to provide a place for a priest to say

memorial

masses for that person or family. Chantries

included altar tables, and the basic idea was

that with each

Mass sung, the soul of the chantry builder would be brought closer to

heaven. In addition, monasteries could also have a hermitage or hermitage chapel either their properties or associated with and under the authority of the monastery. The hermitage would house one to three hermits. Hermits were ususally men, usually monks, and also usually priests. (For more on hermits see my article What are Anchorites? or Rotha Mary Clay's The Hermits and Anchorites of England.) (For more on shrines, see book chapters of Shrines of British Saints, by Charles Wall.) |

||

The Trancepts |

||

|

The first buildings used for

Christian worship reflected the

time and place in which they were constructed. These

‘churches’ were Jewish temples and synagogues, then, as Christianity

spread into Rome, they were basically meeting rooms, or family

homes, where Roman widows were among Christianity’s first

and most

powerful converts.

These widows were hostessess, served as teachers, and provided space for the community to learn from the itinerant Christian teachers who stayed in their homes (there were not yet Christian clergy in the way we understand them today). Early Christians gathered openly when times were good, and as the number of Christians grew the church split from the synagogue and began to consolidate its own political, social, and spiritual identity and sought to express and propagate that identity. The square or round or dirt-floor meeting place, the manor home, the synagogue, the places that had accommodated early worshippers, slowly developed into the churches we recognize today as being characteristic to the East (the Byzantines) and the West (the Romanesque Church). |

||

[Peel, St. Germains Cathedral, Isle of Man, England, southern side with cloister & cloister wall. Detroit Publishing, 1905.] |

||

|

By the middle ages, the western church was built in the shape of the Christian Cross and consisted of two rectangles, one built west (the nave) to east (the presbytery), and the other built north and south (the transepts). The two rectangles crossed each other at the Quire (choir) and the first trancepts may have been built to accommodate growing numbers of Christian religious, monks and nuns, who participated in the divine services. The cross shaped transepts, then, reinforced the symbols of Christ’s sacrifice and resurrection, but on a practical level, they also provided more room as monasteries not only grew in members, but also in wealth and political influence. |

||

[Grotto of the Nativity, Bethlehem, Holy Land, (i.e., West Bank) Detroit Publishing, 1905.] |

||

|

Wealthier, influential

churches,

in fact, had need of more

room still, and some churches had a second or third set of transepts

which were

used as

chantries or to house relics or even for additional northern or

southern

altars. Other additions extended the

walls of the nave, expanded the Narthex, and added towers (originally

used

for defensive purposes) and spires (originally simply bell-cotes). Post-Reformation churches and

cathedrals could be very elaborate, yet they still owed their core

shape to the

medieval, north-south transept church.

|

||

[The cathedral, side, Cologne, the Rhine, Germany. Detroit Publishing, 1905.] |

||

The Vestry |

||

Vestments were the clothing,

robes, and symbolic items worn by clergy

and during religious worship. Vestments became elaborate

representations of what had originally, in the time of the early

church, been simply the every day clothing of the people of the

day. These items became "vested" with meaning according to the

type of item and how it evolved. Robes, shawls, tunics, hats, and

even walking staffs came to denote rank, status, and level of

sanctification.

Vestments were kept in chests in the vestry and handed out by the Sacrist when their use was called for, such as for the daily priest, or for special feasts and occasions. The Vestry itself could be simply a chest in a wall niche in the church, or Sacristy, or be a room in its own right tucked into one of the church transepts. |

||

The Graveyard Few modern gothic-styled horror

movies would be complete without a spectacular graveyard to raise the

hair on

the back of the neck. But graveyards

filled with gravestones and mossy monuments were not part of the church

landscape of the middle ages.

Tombstones

did not come into general use until after the reformation, when a

strengthening

middle class began to compete with the nobility for a share of prayers

and attention. It was then that grave

stones, many of them carved to imitate the memorial basses inside the

church, began to crop up in

the

churchyards.

|

||

[Douglas, Kirk Braddan, Isle of Man, England. Detroit Publishing, 1905.] |

||

| The

faithful of the middle ages

believed the deceased would first spend time in Purgatory, a place

between

heaven and hell, where their sins would be burnt away so their souls

might

enter the perfection of heaven. The

prayers of those on earth, and the goodworks performed

while they

lived (such as donating money to a church or monastery) would shorten

the time

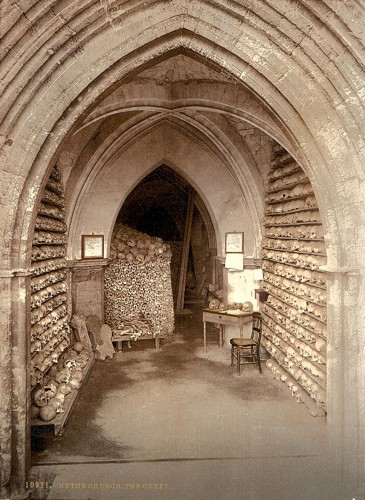

they were required to spend there before entering heaven. The wealthy and influential, then, could gain the appreciation of a monastic community by a generous donation. In turn, the monks would remember them in their prayers, offices, and devotions, thereby speeding the donor's entry into heaven. In addition, monasteries often had strong family and economic ties to important local families and landowners. The burial of the local gentry, and local patrons, patronesses and benefactors within the church, reinforced the idea of the importance of the church within the power structure of the community. Burial inside the church or monastery, then, was an especial honor, and the burial itself was memorialized by some particular marker, either a stone or wooden carving, or by one of the beautiful engraved brasses of the 12th through 15th centuries. (Also see Chantries, under Chapels). All others were perhaps embalmed, usually shrouded in cloth, and buried on the south side of the church (the north side being reserved for criminals, suicides, and heretics). Later, the bones would be dug up from the grave yard and placed in a communal crypt. |

||

[The church crypt, Hythe, England. Detroit Publishing, 1905.] |

||

| Among the monks themselves, a monk of particular position or importance would be interred in the church, cloister, chapter house, or elsewhere in the monastery. All others would be buried in the south church yard. The exception was the Cistercians, who buried their dead in the cloister garth. Regardless of where they were buried, close attention was paid to the dead of the monastery (careful records were kept on Mortuary Rolls). The names of the dead were read out in Chapter for prayers, and, especially on the anniversary of a brother's death, the whole community would pray for the soul of the departed in their communal prayers and daily devotions. | ||

To Parts of the Abbey Church, page one>> <back to top> |

| Historyfish

pages, content, and design copyright (c) Richenda

Fairhurst, 2008-2009 All rights reserved. No commercial permissions are granted. The Historyfish site, as a particular and so unique "expression," is copyright. However, some (most) source material is part of the public domain, and so free of copyright restrictions. Where those sections are not clearly marked, please contact me so I can assist in identifying and separating that material from the Historyfish site as a whole. When using material from this site, please keep author, source, and copyright permissions with this article. Historyfish intends to generate discussion through shared information and does not claim to provide, in any way, formal, legal, or factual advice or information. These pages are opinion only. Opinions shared on historyfish are not necessarily the opinions of historyfish editors, staff, owners or administrators. Always consult proper authorities with questions pertaining to copyrights, property rights, and intellectual property rights. It is my intent to follow copyright law (however impossibly convoluted that may be). Please contact me should any material included here be copyright protected and posted in error. I will remove it from the site. Thank you.  |